"I wanted to make a biopic about Serge Gainsbourg and then people told me about the word biopic – I have no conception of that" – Joann Sfar

Any actor worth their salt will tell you how film is their bread and butter but theatre is their passion. The play is to the screenplay what pantomime is to the biopic, and while an egomaniac like Madonna would have undoubtedly scratched Alan Parker’s eyes out had he not cast her as Evita, her motive for wanting the role was surely her perceived affinity with the personality of Eva Peron above anything else. Indeed, the squabble over casting is often the sole interesting element to these artistically moribund affairs.

There are many reasons why the biopic can be excruciating to watch. Firstly the screen writer’s job is to attempt to portray events the viewer is likely to be aware of, and dramatise them without interfering too much with their already configured memories. Scepticism in cinema-goers is soon awakened should a part fall to an actor who looks nothing like the subject simply because of box office concerns. The rumour that circulated prior to the release of Control that Jude Law was to play Ian Curtis thankfully turned out to be unfounded, though the same couldn’t be said for Telstar, the fascinating story of record producer Joe Meek which was bizarrely handed to first time director Nick Moran and featured a cast of greats including James Corden, Ralf Little and the bloke who played Dennis in Eastenders. Similarly the cynical amongst us who saw Worried About The Boy recently and were old enough to remember Culture Club first time around had to wonder if George O’Dowd had a hand in casting, given how beautiful the actor that played Boy George was.

In a recent, excellent BBC4 documentary Rich Hall’s Dirty South, Hall rages about the "fact"-based music movie:

"Of all the shitty things that Hollywood does to sell films, the absolute shittiest is when they try to crank out some musical biopic. The musical biopic exploits the details of an artist’s life and pigeonholes them and homogenises them, and in the end just lies about it."

Walk the Line is one of the examples he rightly picks on. It’s not just in Hollywood either. Sam Taylor-Wood’s Nowhere Boy was a success where the TV movie Lennon Naked stank, partly because the former was concerned with John Lennon’s upbringing, of which little is known or documented (which only adds to his legend and mystique) and because the actor chosen was plucked from relative obscurity. Christopher Eccleston portrayed Lennon in the latter, and the film attempted to re-imagine the disintegration of The Beatles and the development of romance with Yoko Ono. A fine actor Eccleston may be, but as the caustic Lennon he was embarrassingly unconvincing. As Caitlin Moran pointed out, Eccleston’s penis received more airtime than Paul McCartney. While Lennon’s story is undoubtedly an interesting one, like Mark Chapman, surely the filmmakers could have picked another target. All we are saying is give peace a rest.

Back to Rich Hall:

"The screenwriters of a biopic are forced to attribute character changes to specific events in that artist’s life. But that’s not how life happens. Ray Charles becomes a heroin addict in the movie Ray because his brother died, when in fact Ray Charles became a heroin addict because he kept shooting fucking heroin into his arm. It’s reductive lies, it’s reductive emotion, it’s reductive talent."

Recreating events that probably happened and dramatising them is insulting to the viewer. Oliver Stone’s The Doors is one of the better portrayals of a rock band, or more specifically a rock star, mainly due to Val Kilmer’s physiological similarities to Jim Morrison, and because Val Kilmer is clearly good at playing a drunken, out-of-control arsehole. It succeeds despite the risible scene where the band create ‘Light My Fire’ from thin air within minutes in a practice room overlooking Venice Beach.

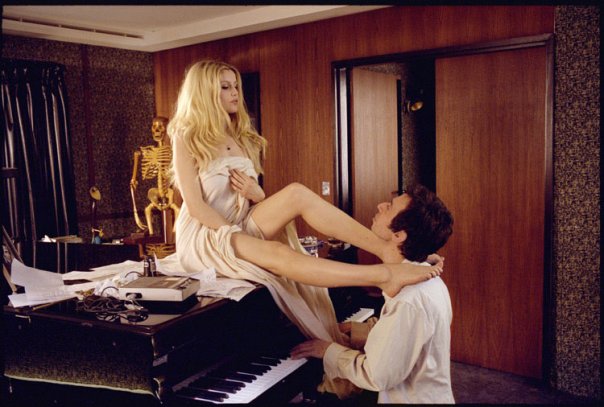

Which brings us to Gainsbourg (Vie Heroique). Though by no means perfect, comic book writer Joann Sfar’s film is a pleasure to behold because of its invention. The debutante director’s instinct is to avoid faithfully retelling a story his French audience will be all too familiar with. Sfar deliberately avoids the pitfalls of the biopic by creating something fantastical and wondrous on screen that hardly resembles reality at all. It also helps that when casting he and his crew unearthed Eric Elmosnino for the title role, an actor so similar in look to Serge that it’s easy to go long periods forgetting it’s not the singer himself. His mannerisms rather than his face on occasion give him away.

"Serge is a Don Juan who is presented for his genius and for his flaws," Sfar told The Quietus. "Nothing is left out. He is a character who loves not to change. It may not represent the truth but it’s the truth as I see it."

As Sfar sees it, the truth is something to take liberties with. Ignoring the obvious reverence reserved for his subject he has taken artistic licence to new frontiers, a far more fitting tribute to a character who himself was ever changing and envelope pushing musically (even if he was obstinate and infuriating where his personal habits were concerned). Sfar, who has been drawing Serge for 20 years now, shaped the screenplay from his childhood memories. Gainsbourg’s notoriety would have been impossible to ignore, and Sfar’s fascination has much to do with the contradictions of this most celebrated anti-hero. "His story is like Jekyll and Hyde. He was a modern Jekyll and Hyde because Jekyll was very sad when he became Hyde," he says.

Gainsbourg famously had an alter-ego, Gainsbarre, who he blamed many of his drunken antics on, absolving himself in the process even when others hadn’t necessarily forgiven him. Sfar toys with this idea throughout the film, giving Serge a number of puppets to engage with which are extensions of himself. There is a spherical and grotesque Jewish effigy which follows the young Lucien around (before he becomes Serge the famous musician). Emerging from a Nazi propaganda poster, Sfar touchingly turns the depiction of hatred into a lovable companion for the boy. Later he is joined by a louche, besuited demon figure with long Jarvis fingers that cajoles him into sexual rendezvous, something an introspective and geeky Serge would be unable to do on his own. Rather than attempt to present reality, he uses the puppets as devices to tell Gainsbourg’s story, a story so rich with incident, so full of escapades and misadventures, that the director was surely faced with the dilemma of what to keep and what to chop. The film is over cluttered and sometimes lacking cohesion as a result, but its unpredictability, the sense that you have no idea what might come next, is ultimately refreshing and above all commendable. Sfar’s inexperience is the viewer’s gain, and you wonder what he might have come up with left entirely to his own devices. "There is a scene in the hairdressers where his nose grows," he says. "In the first version he was to stay like that right until the end of the movie. But people told me, "come on, a French audience will never accept that".

Gainsbourg (Vie Heroique) strays from what is regarded as acceptable in a biopic, and it is all the better for it. If the biopic is akin to the pantomime then this is a pantomime turned on its head. The songs are fantastic, the ugly sisters are replaced with Brigitte Bardot and Jane Birkin and the hero is a devil. He’s behind you.

Join Branchage at the Curzon Soho for a night of film and live music Friday, 30 July 2010, in the bar from 8pm, in the cinema from midnight.

Details <a href = "http://www.facebook.com/event.php?eid=132372303455882#wall_posts

Curzon Soho 99 Shaftesbury Avenue London W1" target=out>here

*Hige Club perform Charlotte Forever by Charlotte Gainsbourg

*Screening: JE T’AIME MOI NON PLUS (Serge Gainsbourg, France, 1976) – GAINSBOURG director Joann Sfar will be in attendance to introduce the film

*Andy Philip & Tim Rose will perform a selection of Gainsbourg songs, from Je T’aime to Johnny-Jane…