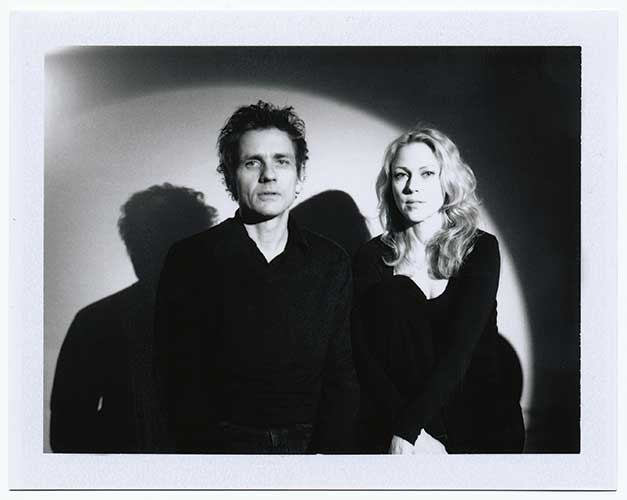

It’s almost a quarter of a century since Dean Wareham formed Galaxie 500 with Damon Krukowski and Naomi Yang. Their prototype slo-fi-meets-shoegaze via The Velvet Underground is currently enjoying a long overdue revival thanks to Domino Records’ recent reissue programme, but since their split in 1991 Wareham has been anything but quiet, barely pausing for breath before forming Luna with Stanley Demeski (ex The Feelies) and Justin Harwood (ex The Chills). Seven studio albums in, they in turn called it quits, but not before Wareham had hooked up with Harwood’s replacement, Britta Phillips, with whom he now records and tours under the unassuming name Dean & Britta. They married in 2007, during the recording of their second album, Back Numbers.

Their latest is an ambitious collection of soundtracks to 13 of Andy Warhol’s legendary ‘screen tests’, silent, unflinching, slow motion film portraits made between 1964 and 1966. Subjects include Dennis Hopper, Edie Sedgwick, Nico and Lou Reed, and Wareham’s continuing debt to The Velvet Underground makes Dean & Britta the perfect choice to provide accompaniment to these previously silent experiments. They were invited to take part by the Andy Warhol Museum and Pittsburgh Cultural Trust, which gave them access to select what they considered the most suitable candidates based on not only the material but also the stories behind the individuals involved. They chose to focus on "the people who were there on a daily basis – young dancers, actors (though Warhol’s ‘actors’ were more often non-actors with no formal training), playwrights, musicians, talkers, speed freaks", but no doubt the back story to some of these characters played a significant role too. As Wareham told the Pittsburgh City Paper, "If you know that Freddie Herko jumped out a window not long after his piece was filmed, that might change the way you look at it."

13 Most Beautiful… Songs For Andy Warhol’s Screen Tests is available as a DVD from Plexifilm, but an expanded double CD edition of the soundtrack contains not only the original 13 songs but a selection of remixes, including four by Sonic Boom. Highlights include My Robot Friend’s remix of the VU cover, ‘I’m Not A Young Man Anymore’ (which naturally accompanies the Lou Reed film) and ‘Herringbone Tweed’, a rewrite of a Luna instrumental called ‘The Enabler’ that fits Hopper’s Screen Test perfectly. Dean & Britta will also perform the Screen Tests show at London’s Barbican on July 30, 2010.

You’ve become something of a ‘renaissance man’ over the last few years: apart from your work with Dean & Britta, you’ve composed music for films including The Squid & The Whale, written a memoir (Black Postcards), recorded music for a series of screenings of 13 of Andy Warhol’s Screen Tests and worked on a DVD (Tell Me Do You Miss Me) about Luna’s farewell tour. Have you experienced a renewed burst of energy in the recent past, and what’s inspired this apparent rush of activity?

Dean Wareham: Spinal Tap points out that when the band breaks up there will be time for all those projects that you never got around to. Being in a band is like being on a treadmill where you rehearse and write songs, then record your album, then go out there and tour the States and Europe, and tour again, before starting all over again. I did this for eleven albums in a row from 1988 to 2004, but now that I’m no longer in a band it has allowed me to do other things.

Working on The Squid and the Whale and Andy Warhol’s Screen Tests – I just consider myself lucky to have been involved with these two directors (though of course Warhol was not there to give direction). It’s not often you get asked to work on a really great film; I think most actors would say the same thing. The Squid & the Whale was special, and these Warhol films are like magic time capsules, beautiful and haunting.

The recent release of Galaxie 500’s back catalogue has confirmed the band’s status in alternative rock’s canon of indie legends. How do you feel about this? Did you ever feel at the time that what you were doing would still be a significant reference point some twenty years later?

DW: Certainly not. I think we were quite surprised when we discovered that at least half of the first session we recorded with Kramer sounded really good. Before that we were just working on songs in a little room, learning how to play our instruments together. We were aware that Galaxie 500 were different from all the other bands in Boston, and I’m sure on some level we felt superior to them (it takes a certain youthful arrogance to form a band anyway) but I know I didn’t consider us to be important. It’s hard to see your own music that way; at least it is for me. But listening back to those records now, I can see that they are just as good as many other albums that I loved at the time – from Easter Everywhere to Colossal Youth to Days of Wine & Roses.

You’ve worked with labels big and small, experiencing the limited budgets of indies and the discomforts that come with that, and the pressure that comes with bigger expectations when working with the likes of Elektra, albeit it with added luxuries. Given the choice, which would you recommend?

DW: I don’t know that I can make either recommendation, it would depend on where you are and what you want out of it, what exactly is being offered. We may be getting to the point where this is an irrelevant discussion; the whole major label system is in retreat, and those added luxuries (like tour support, large recording budgets) are disappearing too. Now some big labels are asking for a cut of the band’s T-shirt income, which is pretty shocking.

I had really positive experiences at indies like Rough Trade (despite the bankruptcy) and Beggar’s Banquet and Rounder, and Domino seem really good too.

I will say that it’s nice to go into a good studio with a vintage Neve console and a collection of great microphones and an engineer who knows where to place them, but you can do this without wasting time and huge amounts of money. I like to work quickly, perhaps I’m just impatient, but it’s probably because my formative recording experiences were with Kramer, who rarely wanted to do something twice. Anyway, you can’t really make rules about this; some great albums are recorded cheaply in three days, others take months and probably cost a fortune (e.g. Exile on Main Street).

Do you think that the days of bands being able to organically develop an audience over a long period of time are gone now that music is frequently available free, now that it’s omnipresent, now that our attention spans seem to have shrunk so significantly? And do you think that it’s fair to ask songwriters to sell their music by touring rather than what they initially set out to do: write songs? Isn’t that rather like the late Mitch Hedberg’s joke: "When you’re in Hollywood and you’re a comedian, everybody wants you to do things besides comedy. They say, ‘OK, you’re a stand-up comedian. Can you act? Can you write? Write us a script?’ It’s as though if I were a cook and I worked my ass off to become a good cook, they said, ‘All right, you’re a cook. Can you farm?’"

DW: Well comedians may complain, but are probably lucky if they get the chance to appear in movies and sitcoms; they can get health insurance that way.

Simon Reynolds points out in his last book that music is fetishised and omnipresent; we are surrounded by it, carry thousands of songs with us on our iPods etc., but it’s less important in our lives than it was twenty years ago. I used to come home from school and sit on my bed and listen to music; now of course teenagers have more modern distractions. Yes they listen to music, but it’s only one of many choices. And as you say, they expect the music to be free.

As to your other point, once upon a time songwriters wrote songs and singers sang them. So songwriters made a living by hawking demos around at publishing houses and record companies (and that is probably still the model in Nashville). These are different skills of course, but I guess The Beatles changed all of that, to the point where the only rock and roll considered to be authentic was made by musicians who wrote their own songs and played their own instruments. If you want to make a record, that’s all very well, but if you want people to buy it you still have to get out there and tour. I’ve noticed this with our own small label (Double Feature) – when I am talking to the distributor about how many copies to manufacture, the first question they ask is "are they touring?"

You seem to make a point of being honest within your work. You’ve never made any secret of your musical debt to The Velvet Underground, while ‘Black Postcards’ and ‘Tell Me Do You Miss Me’ are both pretty naked depictions of what it’s like to be in a band, both highs and lows. What compels you to take this route rather than the safer, more marketing-friendly path that most people would follow when undertaking such projects? Or do you in fact still exercise significant self-censorship?

DW: There were other stories I left out, but mostly because they would have been repetitive (life on the road is repetitive). There’s a line I like from a poem by Vijay Seshadri:

"Orwell said somewhere that no one ever writes the real story of their life. The real story of a life is the story of its humiliation."

I wanted to include the humiliations, whether self-inflicted or not, and tell some painful/funny stories even if they didn’t always put me in the best light. I’ve read other memoirs where I felt the author pulling back, or not telling the whole truth, and I think the reader can sense it. I didn’t want to just write a puff piece of pithy observations about the music and people I worked with, and leave out all the difficult stuff; I wanted to tell a story that worked even for a reader that knew nothing about me.

You have been described as a veteran of indie rock. How does that make you feel, and do you consider the theory that "it’s better to burn out than fade away" outmoded and irrelevant these days now that rock music is no longer the preserve of youth alone?

DW: I admit I felt old when I saw ‘Tugboat’ on VH1 Classics. But I can’t argue the point about being a veteran of indie rock. It’s just that ‘indie rock’ today is a very different animal. Just like ‘punk rock’ became almost the negation of what it stood for. I don’t know what ‘indie rock’ is today but I do know it is big business.

And I’ve never quite understood that line "It’s better to burn out than to fade away." Is it better to be a rock and roll victim and choke on your own vomit? I would rather live. I prefer Jonathan Richman’s lyric: "Someday we’ll be dignified and old."

Despite such a status – the New York Observer also called you a "New York rock god" – you’ve never really achieved the levels of success of which critics and fans felt you were worthy. Why do you think that is, and do you get frustrated by this? In an interview with Salon I noticed you comment about one Luna album, "Well, we thought we had some singles on Penthouse but we were sadly mistaken. As usual." There seems to be a strong hint of regret and resignation in that comment. Do you feel that way a lot when you look back over your career?

DW: I think real fame is an adolescent fantasy, something that few people achieve, and it would be childish of me to complain about not getting there, or not selling millions and millions of records. Maybe we never recorded the right song at the right time, maybe my odd voice was never going to get real radio play, but it would be silly to get angry about this, to complain that Stone Temple Pilots got big and Luna didn’t – they were doing something in tune with the zeitgeist (and a certain radio format) and we weren’t.

Black Postcards and Tell Me Do You Miss Me rather ruin the illusion (much like Radiohead’s Meeting People Is Easy film around The Bends) that being in a semi-successful indie rock act is glamorous and exciting, when it’s instead largely comprised of endless waiting around, long journeys, disappointment, compromise, personal tensions and frustration interspersed with only a few moments of wonder and artistic fulfilment. Did you lean extra heavily on the negative aspects in order to make that point and dismiss the mystique, or do you genuinely find the routines of being a musician a heavy weight? And do you think that you’re at all bitter about the way things have worked out for your musical career, or are you content with the way things are?

DW: Perhaps I should have written more about the positive experiences (there were many); but all writers exaggerate. Especially in lyrics: you expand on how awfully sad or angry or depressed you were to make it more interesting. Also maybe you stress the negative aspects when you are ready to end something, looking to make a change; you work to convince yourself that it’s all intolerable. Matthew Buzzell made the film right as Luna was breaking up, when I think we were all ready to move on. When I watch the film now I see someone (myself) who looks to be going a little crazy. It was a tumultuous couple of years. Anyway I’m glad we have the film, I thought Matthew made something really poetic out of the hundreds of hours of following us around and filming our shows. The waiting around and long journeys – that I did not exaggerate. Touring can be a grind, though lately I am really enjoying it – perhaps because we tend to go on shorter trips, a week or two at most.

To answer the last question, of course there are times when I feel cynical about my career and about the music business, but no, I am not bitter. There are things I would do differently if I could, but for the most part no one stole from me and no one owes me anything.

I have a friend who can barely listen to ‘California’ (from Luna’s Bewitched) without tearing up: how does such a statement make you feel as an artist? Do you think that the knowledge that your songs and performances have provided inspiration and comfort to fans, however many or few, can be compensation enough for a musician?

DW: I do take satisfaction from that – though ‘California’ is not a sad song, so maybe it just reminds your friend of a time in his/her own life. I mentioned in the book, that I received a letter from a 17-year-old in Sweden who said she and her friends had watched the sun come up while listening to On Fire, and yes that is kind of wondrous, to know that something you recorded 15 years earlier is entertaining people half way around the world at 5 a.m.

Many people compare being in bands to relationships, something that can go sour without anyone actually wanting it to end or even understanding why. Did the breakups of Galaxie 500 and Luna feel like a relief? And don’t you worry that the same could happen now that you’re in a band with your own wife?

DW: Leaving Galaxie 500 was a relief; I felt free. The problem there, beyond ego or personality or all the other petty stuff, was the very structure of the band – a trio containing a couple, which I think is an unstable situation over a period of years (Yo La Tengo are the exception that proves the rule). The breakup of Luna I was sadder about – we had been doing it much longer, and we parted on better terms. Not that there weren’t tensions in the band – there surely were – but it was hard to stop after all those years together.

Anything could happen to Britta and me, but I don’t think we’re at greater risk from working together; so far it has been an ideal situation. She’s a really smart musician and more patient than I am; she arranges and engineers and mixes a lot of the music that we record at home. Anyway Dean & Britta started as a side project; we don’t expect to make seven albums; but we have other things we do together too – like the film scoring.

Your latest project sees you providing a soundtrack to screenings of 13 of Andy Warhol’s ‘Screen Tests’. You’ve also played shows with Lou Reed, and your music is rarely discussed without mention to the Velvet Underground. Don’t you ever worry about being too closely associated with this camp, and did you hesitate before accepting the 13 Most Beautiful… project, or did you simply feel that you had something worthwhile to contribute and accept that they remain your muse?

DW: This is what Harold Bloom called "anxiety of influence." I don’t worry about it too much, the Velvets are an influence on my life but so are the Bee Gees, Lee Hazlewood, Jonathan Richman, Talking Heads. And the critics will say what they want, they compared Galaxie 500 to the V.U. at the time but if you listen today those Galaxie 500 albums sound like no one else at all, and I would say the same for Luna.

You’ve had to put up with a certain amount of resentment directed towards you on the basis of your background and education. You’ve certainly not been alone in having such vitriol aimed in your direction, with the varied likes of Joe Strummer and Keane both being judged on the basis of things (i.e. their past and their upbringing) that were, arguably, beyond their control. Do you think rock music suffers from an uncomfortable level of inverse snobbery?

DW: It might be more acute in England than it is here. I mean Joe Strummer hardly came from great wealth, but punk artists were probably especially vulnerable to this charge. And yes, some people resent you when they hear that you went to a good school; it’s funny to me when they also assume that because you went to that school you must therefore be living on a an inheritance. Anyway, who really cares – it’s the music that remains.

What do you feel have been your greatest artistic contributions to the world, what have you got lined up next, and would you ever consider reforming Galaxie 500 or Luna and reliving past ‘glories’?

DW: The achievements are the recordings, or at least the best of them, rather than the songs themselves. ‘Tugboat’ is a sliver of a song, two chords, a couple of interesting lines perhaps, but the recording has something magical to it. And I could say the same for ’23 Minutes in Brussels’ by Luna, or an obscure B-side like ‘Egg Nog’, one of the best things we ever put to tape.

My favourite response to the eternal question about re-forming the old band is David Byrne’s – he says it’s like expecting that you’ll get back together with your teenage girlfriend. The answer is no, you broke up years ago and have moved on with your life and it wouldn’t be healthy to be back in that relationship again. But I’m happy to play the songs – this fall I’m going out and doing a handful of shows where I’ll play all Galaxie 500 songs, backed by our regular band. I did this in Paris last year, and I have to say I get a real jolt of emotion playing those songs again.