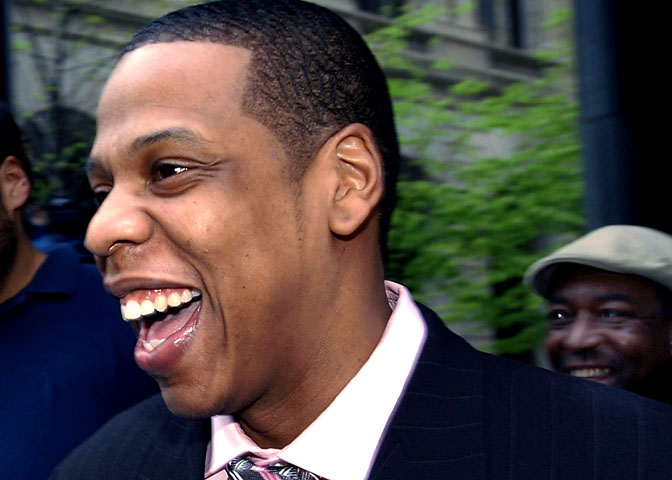

The announcement of Jay-Z as headliner at Glastonbury has been as unwelcome for many as thieves skulking around the camping areas. Slumming it for three days is an integral part of the appeal of festivals, but the idea of a taste of the real, actual ghetto intruding into the blissed out festival utopia? That obviously won’t do.

You’d expect a curve ball like Jay-Z, who most indie kids would probably never see elsewhere, to be a welcome bonus to the line-up, not persona non grata. Besides, all other things being equal, who wouldn’t want to see the most influential rapper of the last decade? Compared to pop footnotes like Razorlight and The Zutons, or the execrable light entertainment of Rod Stewart, Robbie Williams and Shirley Bassey, all of whom have featured in recent years, Jay-Z is practically a colossus of western culture.

Although he’s now in the autumn of his career (his finest moment still being his stellar 1996 debut Reasonable Doubt), Jay-Z is still an astonishingly nimble lyricist, when he’s not messing around with record labels and sport franchises. More importantly, he’s one of the few rappers with the intellect to cut keenly to the core of what’s rotten in the heart of American culture. His hyper-capitalist "businessman" persona may jar with Glastonbury’s happy-clappy positivity, but anyone who observes a race-divided nation where "all these blacks got is sports and entertainment" (the kind of sound-bite you might expect from a presidential candidate) is a man we should be listening to.

So why the beef? Perhaps the perceived violence of current rap? Go through Reasonable Doubt though and there’s little actual glorified violence. The most gangsta track, the drug war reportage of ‘Friend Or Foe’, is a battle of words, where a patient but coolly ruthless Jigga slyly persuades some wannabe drug slingers to go and ply their trade elsewhere. There’s certainly something of a nihilistic streak to Jay-Z’s work, but its not clear why this should be beyond the pale where, say, the coke and booze hedonism of Oasis or the southern decadence of Kings Of Leon is acceptable. He’s an unrepentant lover of the green, but so is Shirley Bassey in ‘Hey Big Spender’: it’s only the latter’s sepia-tinged nostalgia is which distances it from Jay-Z’s more upfront mo’ money moves.

The main reason to appreciate Jay-Z, though, is a word craft and delivery which puts virtually all contemporary guitar slingers in the shade – something you might miss if your only acquaintance with him is guest appearances on Beyonce tracks. Jay-Z’s flow always remains as even and calm as if he’s giving a state of the union address, yet interpolates all kinds of lyrical twists and meta-referential jokes with unerring detachment and poise, the lines spilling over with organic word play: "While y’all pump Willie, I run up in stunts silly/Scared, so you sent your little mans to come kill me/But on the contrilli, I packs the mack-milli." The subject matter is borderline amoral, but the sweep is always cinematic: "I remember tellin my family I’ll be back soon/That was December….. Eighty-five…" Jay-Z’s ability to distance himself from his deeds give his music an acute self-awareness. He’s one of the few rappers able to detach himself from a situation to cooly consider himself from outside: "OK I’m gettin weeded now/I know I contradicted myself, look I don’t need that now/Its just once in a blue when there’s nothin to do/ and the tension gets too thick for my sober mind to cut through/ I free my mind sometimes I hear myself moanin/Take one more toke and I leave that weed alone, man." But if Glastonbury wants people to rock the stage, Jay-Z’s recent work achieves that effortlessly. Whatever you think about the slack sexual politics of ’99 Problems’, its soul shout rhythm and relentless tirade against police harassment is absolutely irrepressible, and ‘Brush Your Shoulder Off’ is similarly ferocious.

In many ways, Jay-Z represents where hip-hop grew up. Sure, his nihilism can be hard to square with Glastonbury’s uncomplicated positivity, but his refusal to deal with moral blacks and whites has an ethical integrity that you won’t find in gullible pro-charity cases such as Coldplay and the new breed of Live Aid bands. Those who think Jay-Z contradicts Glastonbury’s principles is surely overestimating how much difference a party in a field can really make to geo-political realities, and if Jay-Z doesn’t play along with such myths, that’s something to be cherished.