I can’t be the only one cursed with perfect recall of all the records – their lyrics, running order, even their lulls – that I loved before I reached, ooh, 15, the age when my concentration was disrupted forever by the concept of romance and its necessary complications (I had little to offer the ladies of course, even if I knew every word of All Mod Cons, Entertainment! and Unknown Pleasures). Somehow it comes as no surprise to learn that Nick Kent, by his own account a man who spent the seventies having the word ‘poof’ yelled at him, didn’t pop his cherry until he’d left single-sex secondary education and made it to college. By the time he entered adulthood, with its horrible uncertainties and irritating responsibilities, he’d built up a complete backlist of simple verities to fall back on, the easily digestible soundbites of rock. No wonder he chose heroin and its comforting guarantee of binary lifestyle choices.

The first thing that strikes the reader of Kent’s long overdue seventies memoir Apathy For The Devil is that he’s actually quite embarrassed about his youthful idiocies, even though he knows that without some tales of sleaze to share no one would be interested publishing, let alone reading, his book. This one time golden boy of rockcrit is pushing 60 now, he’s been a family man and steady provider for over two decades, and what has all that youthful promise led to? One compilation of old journalism and now a memoir that casts no one in a good light. These days he’s just a man that knew Keith Richards nearly forty years ago.

Still, confronting his own young self, that lad who spent a lot longer in squalor than glamour, can’t be easy. Some of Old Nick’s inevitable reconnection with Young Nick is expressed harmlessly in his adherence to an ancient kind of rock speak that was outmoded by 1980 – I haven’t seen the word ‘zeitgeist’ used non-ironically in decades, while some of his opinions would be bracingly windy if they weren’t so dull. And some of it is like an AA devotee making amends for all his bad behaviour. It makes for a weird mixture of self-deprecation and self-importance, all interspersed with several reassuringly petty factual errors, long a Kent trademark (in the original edition of his best of, The Dark Stuff, the word ‘ineptitude’ was misspelled at one point).

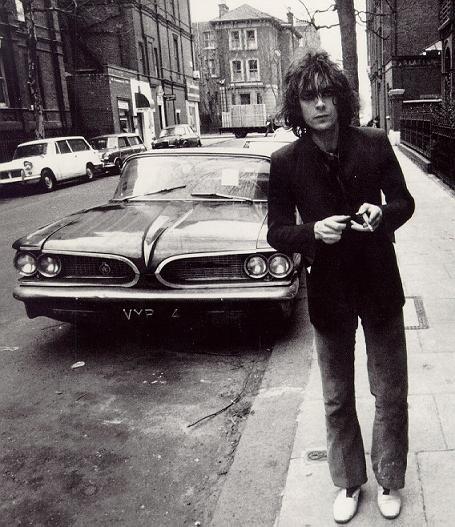

It’s an unusual mea culpa, a man effectively explaining away his inability to ever quite crack it and exploit his undeniable talents on something more significant than mere tales of rock musicians. That’s not intended as a deep swipe – Kent’s best pieces were, and remain, bloody good for such a young man, and at the time offered an unusually clear-eyed analysis of those damaged by their uniqueness without shying away from more lurid aspects. Yet as a man who lived in the shadows (his description) of the truly exalted and blessed, his only recourse – in fact, the only way he can give his half-lived life meaning enough to fill a book – is to overstate the mythical nature of his subjects’ achievements. He might have strummed along in his time, but he never came closer to the big time than being unpleasantly bullied out of an early iteration of the Sex Pistols (he stood a generation apart from McLaren’s target demographic for trouser sales. And was a great big junkie to boot).

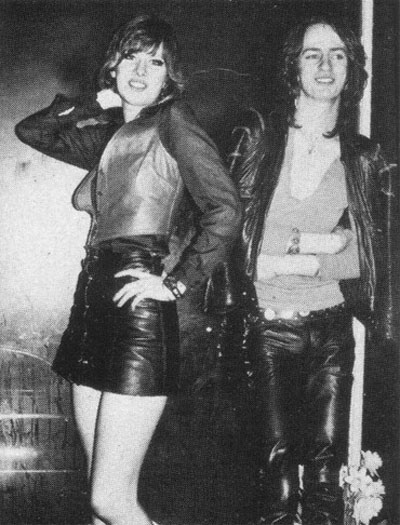

If anything, Apathy… is an elegy to something he’s lost and knows can never be recovered. For all its bluster and even ridiculousness (his ‘choose life’ moment in a rural church certainly got me exclaiming ‘Jesus Christ!’, while the revelation that his girlfriend’s performance art career is threatened by the loss of her tightrope could make for an entire junkie comedy) this is one rueful tale, and if it weren’t for the celebs that pass through, it would have no meaning at all. It certainly took place in a void – the outside world of the Vietnam war and miner’s strikes and oil crises and IRA bombs makes no appearance at all. Hell, there’s not even a reference to heroin getting cheaper after 1979’s Iranian revolution.

Kent does make one charming point though, suggesting that he – albeit by accident – really did live through a golden age, when huge bands played relatively tiny venues at reasonable prices and, though he doesn’t mention it, record companies had huge promotional budgets. Football was cheaper too with a riot every other week, and Play for Today was always a must-see. And chips came wrapped in newspaper, as did amphetamine sulphate. God, it must have been great.

This perpetual urge to imply that historical narrative is not merely worth recording, but truly significant (make that ‘quintessential’) is an eternal problem with rock books. Last year John Harris, formerly of NME and Select but now more often employed by The Guardian as a centrist vox pop specialist forever taking the nation’s political temperature, pressed some people’s buttons with a not especially well argued piece that suggested that present-day rockcrit wasn’t as good as old time rockcrit. No one likes to be told they’re effectively redundant, so responses were hostile from contemporary critics, and Harris’s suggested canon was neither original or controversial (St Les Bangs aka the Jeff/Tim Buckley of rockwrite, Kent, Greil Marcus, Simon Reynolds IIRC). There were some odd omissions like Tosches, Cohn and, particularly, Peter Guralnick, whose calm exhaustiveness would seem a shoe-in for Harris’s relative traditionalism (if he can hold his nose long enough, PG could yet write the definitive Michael Jackson story).

Whatever your viewpoint, that’s a pretty thin list, as is that provided by dissenters. The question it raised is surely ‘why are books on popular music so crappy?’. It’s not as though journalism or criticism is dead. The internet offers everyone a chance to interpret at a distance and express themselves, should they choose to. But its very instantaneity speeds up the inevitable process between curiosity and cynicism. I accept that I am now a boring old man more likely to be impressed by a cheese or an unusual wine than some new indie band or yet another variation on 4/4 being passed off as a new sub-genre of something or other. Yet the idea of enjoying a copy of The Wire (the magazine, not the telly show) then actually hearing the sounds so lovingly evoked, is oddly depressing. Imagination was once the most important force in music criticism for the reader. Today easy access means that you can hear it as soon as you’ve read the blurb, virtually a guarantee of disappointment.

Novelty though is exactly what drives music writing, the weird desire to point out who heard what first, even while making someone else richer. And novelty is just what publishing cannot offer, the odd cash-in aside. Publishers’ wheels grind slow. They make record companies look like housebreakers shifting swag at a car boot.

Logically then, long form writing should at least be able to work a new and successful niche for itself, separated from the pressure of deadlines or having to offer an instant opinion. But it doesn’t. How many critics even make the leap to other forms? Nick Hornby is now a very wealthy and successful man, but not because of his never very well-respected record reviews. He has made pragmatism work for him. Stay romantic and you stay poor. Take two stories – the revelation that the Stooges’ James Williamson had spent the last 30 years hiding in plain sight as a Sony executive. Hornby once told me he could never write sport into his fiction because knowing the truth of who had really won that year’s Cup final would bother him to distraction. When I pointed out that the plot of his own About A Boy was hung on Kurt Cobain’s death being announced on the front page of the Evening Standard – something which never happened as news didn’t get out until Friday at midnight – he described it as ‘artistic licence’, not wholly joking.

Bluntly, publishers don’t take music writing seriously. Too many books are shoddy biogs, scrivened for coins, or screeds that ought to have stayed blogside (there are honourable exceptions obviously- to name but two, Faber and Faber are working to widen their music list and Continuum’s 33 1/3 series is never predictable).

But those charged with writing them are desperate to show the opposite. So music books often have a queasy tone, where any genuine erudition seems unsure of itself, or they’re sloppy in a way that wouldn’t be permitted elsewhere on the publisher’s list (the original Penguin edition of Kent’s Dark Stuff actually gets the names of interviewees wrong). Major publishers like unexpected hits, but can’t predict them with any accuracy. The late damaged extrovert Viv Stanshall would seem a better bet for a profitable biog than the late damaged introvert Nick Drake, but it was the Drake tome that shifted (both were crap though). Specialists have a far better idea of how many they’ll sell and budget accordingly, but they also know that sales won’t go past that core number.

This isn’t to say there aren’t decent music books. Of course there are. Choose a big subject, or one with wide resonance and get a sympathetic editor and you can mark a territory in eternity (Hoskyns on LA or Savage on punk, for instance). But compared to just about any other genre, the essential music library is tiny. Bangs now exists as a couple of paperbacks, one patchy. Kent’s career has proved as unproductive as the burnouts he once specialised in eulogising. When the inevitable Steven Wells reader comes along, shorn of context, will it matter like it did in weekly doses? Maybe journalism, with its jittery opinions works best in the greatest hits format. Just like popular music itself, here today and gone tomorrow, led and discarded by fashion. One minute you’re listening to garage, the next you’re being ripped off by one. Which doesn’t solve the problem with so many books.

The temptation for authors to imply true significance must be irresistible. Effectively Kent wants us to believe that by being closer to his subjects, once, he offers deeper insight. And next to the PR-whipped hacks of today, he might have a point. But biographers from Ellman to Kershaw don’t seem to have this problem when composing mighty multi-volumes. It might just be that music isn’t very important, and the people who make it aren’t all that interesting. What that makes the men (and they are so very often men) who document their actions is moot.