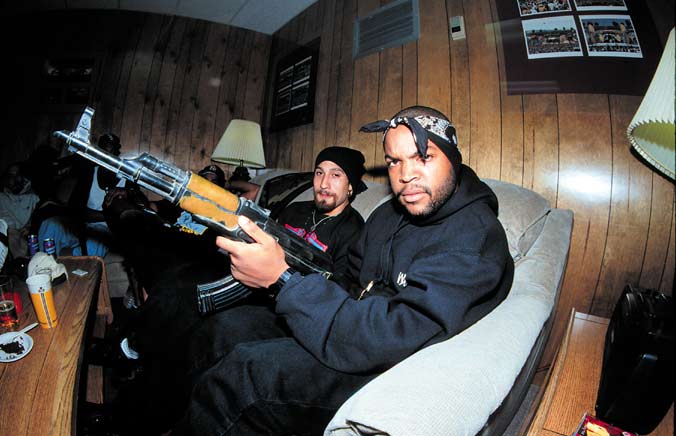

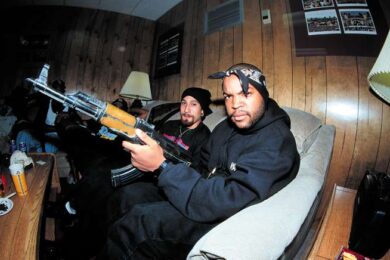

O’Shea Jackson, as no-one ever calls him, was once a legend in his own lunchtime, a name to drop among cognoscenti of both hip-hop and modern politics. Between 1990 (when his old band Niggaz With Attitude first came to prominent infamy) and 1994 (when everybody suddenly started listening to Dr Dre instead), Ice Cube juggled several personae – the ghetto prophet issuing dire warnings about impending social collapse, the scowling ‘hood film’ actor, the music-biz prime mover who faced down Louis Farrakhan and Oprah Winfrey with equal nonchalance, and of course the rapper with the most vitriolic, controversial songs in hip-hop. Later on he added ‘film director’ and ‘businessman’ to his CV, as well as diverting his initially serious acting into comedy and action roles. All this made Cube into one of the most significant figures in American culture, with his profile peaking in 1992 after he released The Predator, a dire commentary on the riots which had decimated parts of his home town of Los Angeles that year.

Ice Cube has a new album out called Raw Footage, released on his own Lench Mob label in the US but with no UK distribution deal yet announced. In an inverse of his early-1990s career, he’s now an actor with a mere sideline in music, with no major-label backing and no great enthusiasm visible in the press or industry for his new product. When he played a show in London in summer, it was at Camden’s Electric Ballroom, a dusty, slightly dilapidated club with a capacity of 600, rather than the major venues he used to fill a decade and a half ago. He’d spoken to the press beforehand about the nature of the show, explaining that he was planning a stripped-down, ‘old-school’ show with only two turntables and a microphone – but somehow this sounded to me a little like Spinal Tap justifying their reduced tour revenue by saying that their audience was now ‘more selective’.

Not that this really matters. If Cube wants to take a few months out of his movie schedule to hawk his new album to the public, let him. If said album is a load of tosh, it’s hardly important: his set contained enough catalogue classics to make it worthwhile. No, what matters is an address which he gave the Electric Ballroom crowd towards the end of his 75-minute set.

"Hip-hop started in the underground," he began. "Then the major corporations like Viacom got into it. Too far into it. Now the music is back on the streets – where it belongs." While this describes his own musical career trajectory perfectly, there’s a sizzling hypocrisy behind his words which had many of the gig audience open-mouthed in shock and/or amusement. After all, Cube is hardly in a position to criticise America’s large entertainment companies, having merrily pocketed vast paycheques for his movie roles since 1991, when he played the character Doughboy in John Singleton’s classic Boyz N The Hood. He’s reported to have earned $10 million for his role in 2002’s Barbershop, co-produced by MGM and his own studio, Cubevision. Did he say no to MGM’s chunk of movie budget because of their large-corporation status? Hell no. Then there’s the dreadful Ghosts Of Mars (2001), which was distributed by Columbia in many territories worldwide, whose music division has been "too far into" hip-hop artists such as Cypress Hill, Kurtis Blow, Chuck D, Da Brat, Nas, Lauryn Hill and many others for decades. Meanwhile, Cube’s best film, 1999’s George Clooney-starring Three Kings, was a Warner Brothers picture. How big a corporation do you want? The list goes on.

However, let’s be clear about the issue, as Cube wasn’t on stage in Camden. His big mistake is not that he criticises major corporations for being over-involved in music – we all know that when The Man gets hold of a product belonging to the people, the little guy always gets royally screwed. We understand that. His mistake was that he didn’t recognise and acknowledge the interconnected nature of America’s 360-degree entertainment business and modify his comments accordingly. Stating that big business is bad for music is massively oversimplifying the case in the modern era, and today’s music fan is informed enough to understand that. If Cube wants to criticise, he should do so fairly, clearly and in depth – perhaps via a blog like his older and wiser contemporary Chuck D of Public Enemy. Perhaps then he’d be taken seriously as the éminence grise of hip-hop, as he seems to wish to be. Think about it, Mr. Jackson, next time you "take the motherfuckin’ stand" (™ NWA, 1988).

Joel McIver is the author of Attitude, the Ice Cube biography published in 2003 by Sanctuary Books.