“Mysterious and glamorous as Notorious” is just one way synthesizer pioneer John Foxx described what he wanted his landmark album Metamatic to sound like. The album is 40 years old this month and its impact is still being felt. Some would say its observations on the pressures of our identity wrestling against the tides of change in urban life are more prescient now than ever.

I caught up with John to ask him what brought him to write Metamatic, and what convinced him back in 1979, after leaving Ultravox, that "electronics were the future".

New Years Day 1979 and Ultravox are dropped by Island; in February they split. By January 1980 you had released your first solo single and album on your own label and made a video – expensive at the time. How did such a swift transition take place in just under a year?

John Foxx: I’d already written much of the material for Metamatic. This was a point I’d seen arriving – electronic music as escape hatch from that rock lifestyle. (It’s a personal inadequacy – have to go in for repairs too often to be a proper rock star. Need a bit of quiet now and again).

Also a bit much to ask four other people to wait out your risky personal preoccupation with a new, untested form.

JF: So it was a great relief to be finally working quietly, lost in London, accumulating a tiny collection of electronic lifeforms and cycling down to the studio every morning in my grey mac. Wobbly but fun.

With Ultravox you worked with synthesizers and drum machines in a rock-band format then went almost completely electronic for Metamatic. What convinced you that "electronics were the future"?

JF: Cheap instruments alter music – in the 1960s, effective guitars came into financial reach for the first time – and this changed everything. Synthesizers got to that point in the late 1970s. First cheap synths = Here we go.

I also loved the bleepy, violent sound of synths and particularly drum machines – that cool, remote, alienated, defiant precision suited me perfectly. These instruments made shapes that fitted the ones waiting in my head.

You see, there was a new kind of European music in the wings. Much more potential- more fascinating and dangerous and connective and complex and interesting than all that parochial brat whimpering around Punk in late 1977, when everyone thought the funeral was a baptism.

Punk impressed me with that swift decline into conservatism. It succeeded so well, but so briefly, because it confined itself to a very narrow base. I really wanted something a bit wider.

A New European Music was the goal. Cool as Last Year in Marienbad. Dangerous as Un Chien Andalou. Mysterious and glamorous as Notorious. Tragic as A Taste of Honey. Sad as Kes. Something capable of describing our lives in terms a bit broader than shouting at the wall.

You said that whilst recording Metamatic, you were "reading too much J.G. Ballard" yet there also seems to be a deeply personal theme to the song writing on the album. There is a pervasive sense of transition – in environment "Waking up in the moving windows"; in life "The old streets overgrown, there’s somewhere else to go"; in those around you "He’s adhesive, he’s a trickle down a falling wall/ He was a new kind of man" and yourself "pushing through my outline/ It feels like someone using my eyes/ Someone takes my place." Clearly this was a transitional period musically but were you also reflecting transition in yourself, your environment and friends at the time?

JF: Yes. Spot on.

Everything was changing. Friends mutated into unrecognisable beings. Ballard and Burroughs designed the grammar. John Cooper Clarke and Mark E Smith were becoming prefects.

I’d had to consciously abandon the North. The past was entirely dysfunctional and so was I. The North of England was an environment of overgrown factories – an entire vanished way of life.

In many ways I loved it – some of it was warm, beautiful, vulnerable and hopeless. Some of it funny and daft. But some of it was also callous, dark, stupid and cruel.

All that remains is a powerful set of memories, interlocked with a vast territory that no longer has any function. The factories are gone. No structures. Gene pool depleted. People marooned in the rain.

I found it all unbearable, and had to leave.

So I went to London and redesigned myself.

Foxx is much more intelligent than I am, better looking, better lit. A kind of naively perfected entity. He’s just like a recording, where you can make several performances until you get it right – or make a composite of several successful sections, then discard the rest.

Of course it was all a little clumsy at first, then slowly, I began to get my own grammar right. It gradually became a bit more refined. Then it actually became practical. No one was more surprised than me.

The music consolidated first and pulled the rest along. Like that scene in Un Chien Andalou, where the priest pulls a piano loaded with old donkey heads along up the stairs.

The music, though, was another matter – Finally had a place to put all the little things I’d been accumulating for years. It all seemed to become as real as slabs of concrete. I was beginning to make stuff I hadn’t heard before – cheap neon tunes that seemed as big as Europe, as lost as service station on the Berlin corridor. Bits of movies, bits of stuff I’d heard in passing, hitch-hiking around Europe in the 1960s. Gently poisonous, achingly romantic. Slightly deluded, brave and daft.

Then I noticed things beginning to happen without any effort from me, always a sign that the train of inexorable circumstance is moving your way – for a while. Enjoyed the ride. Got money. Got identity. Got a place to call my own.

All this really enabled me to do what I like best – getting time to walk around London and other cities. I could afford to became a ghost. Quietly pleased with it all. Did this for several pleasant years before circumstance intervened. Then, imperceptibly, things gently fell apart, as always.

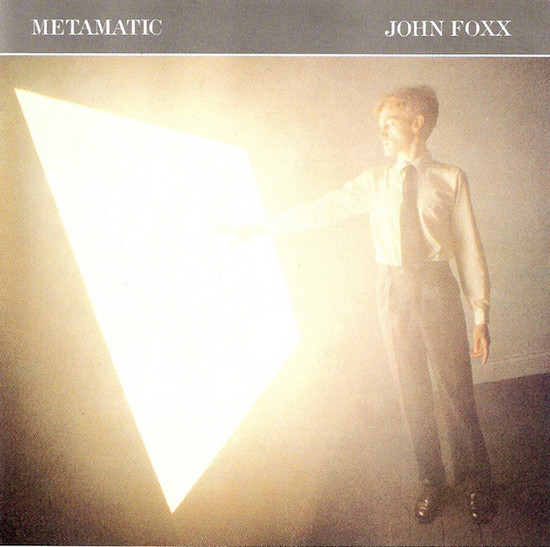

Eventually I had to abandon Foxx. He had no function any longer. Former self looking back at me from record covers in Oxfam.

Hung the grey suit at the back of the wardrobe. It waited there for years. Then, surprise, surprise, it came back to rescue me. Gave me something to wear. Just in the nick of time. Strange how things turn out.

When people talk about Metamatic, they sometimes refer to the primitive minimalism of the music. Was this deliberate or were you on a budget?

JF: Ha! Both. I wanted to allow the synths and drum machines to sound like they really did. No sonic polish. Lots of raw edges.

Carcrash music tailored by Burtons. Blackpool Neon Tango.

I spent hours taking out every element that wasn’t necessary at any given moment. I wanted complete focus on each sound.

No one seems to mention or notice the psychedelic undertones that resonate through Metamatic. Was this a conscious reaction to the music of the time?

JF: I’d loved the idea of electropsychedelia ever since I heard ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’ in the 1960s and experienced a moment of revelation on Chorley recreation ground. But the sixties didn’t have time to realise itself before it was all over, so all the good ideas had to wait. Get distilled by time.

Electronic music is the bastard child of that sad old psychedelic revolution – I was lucky enough to see it when it was fresh as a June dawn, before Manson, Leary and Hearst defecated all over it and everyone lost heart. So I’d remembered that lots of other things got lost too.

Just as the kids of hippies often seek revenge on their parents by becoming accountants and solicitors of the most ruthless kind, so electronic music took all the sublimated psychedelia, all the best bits – an acute awareness and receptivity to time and place, a minute observation of a single moment and an ability to have fun making startling connections – then applied all that to a post punk do-it-yourself ethic.

Suddenly we had a new electromechanical ecology of synths and drum machines which allowed us to address new themes – the unrecognised present, Europe, motorways, the romance of urban environments and the devising of a mythical sexuality that was unspecific and more concerned with shifting identity, elusiveness, transformation and merging.

Everything became timeless, stylised and extended, instead of that quick little ball of flame that characterised rock.

I guess I really ought to try to explain what I mean by psychedelia. I realise it’s all highly personal and accidental – stuff that impressed me for a couple of moments when I was very young and has remained as a touchstone of value ever since. I know it doesn’t mean the same to anyone else, but it’s been endlessly useful to me.

Psychedelia – but only the British and early German kind – is an almost overlooked central tenet of 20th Century music. But it only really exists between. It connects things, really.

I think it informs everything interesting, and it’s the only thread that connects Breton to Dylan to Velvets to Cage to Can to Eno to Europe to Lennon to Burroughs to Ballard to trance to dance to Vogue to poetry to video to art to sci-fi to movies to performance to rock – to everything that comes in the future.

It’s a spontaneous, overlooked, folk activity, based on fun, magic, science and a gloriously misplaced trust in instinct.

It always insists on rebirth and regeneration and return to certain inalienable principles of unpredictability, spontaneity, utility, convulsion, fun, detachment allied to total involvement, episodes of sublime integration and alienation, tranquillity, serene velocity and feral expression of outrage.

When it’s not called psychedelia it gets adopted and renamed but it always seems to get sick and thin. That’s when you catch it sneaking back out into the street for a bit of daft fun.

Something like that.