Soloists, bands and fans may beg to differ, but there is a case to be made that the duo could well be considered the fundamental unit of rap creativity. Notwithstanding the existence of larger groups from before the music’s first appearance on record, and the early emergence of the superstar solo artist either side of the turntables, there is something that feels definitive about a two-person team. For every LL Cool J or Public Enemy, every DJ Shadow or Invisibl Skratch Picklz, there’s a duo whose work will have implanted itself in the listener’s head and taken root for life. They run the gamut from the DJ and the emcee (Eric B & Rakim, Gang Starr, L’Orange and Jeremiah Jae) and the pair of vocalist-producers (EPMD, Run the Jewels) to the creative partnerships that come together for a series of different projects (the Neptunes, Missy and Timbaland) – and they are as central to the evolution of rap as the guitar-bass-drums trio is to the history of rock.

At first glance OutKast are another to add to this long list, yet there are reasons to suggest that, rather than being just another great hip hop duo, Big Boi and Andre 3000 took the concept of rap tag teams – indeed, perhaps of duos in any creative field – as far as anyone is ever likely to go. Over the course of the six studio albums released under their collective name, they explored the extremes of what a musical partnership could be more fully than anyone before or since. Two anniversary reissues, both arriving within a month of each other at the tail end of 2023, provide an opportunity to look at both ends of that scale.

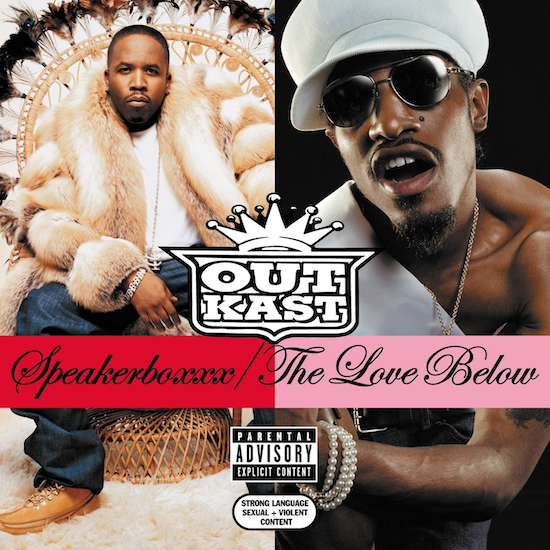

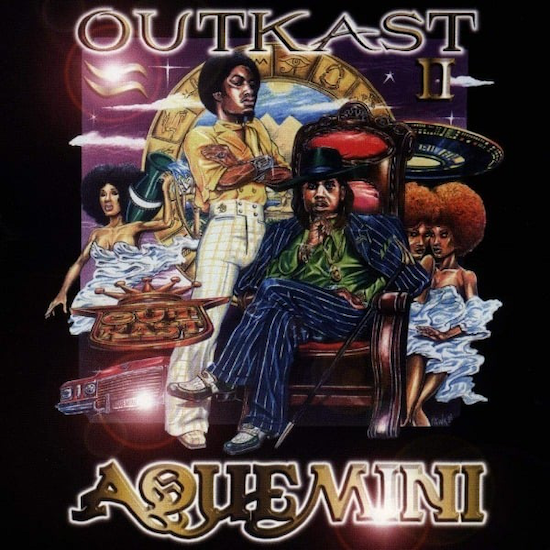

OutKast’s third LP, Aquemini, originally released in 1998, owes its existence in its final form to the fact that, even then, the pair’s partnership was already one understood to be freighted with as many contradictions and personality clashes as complementary elements. The title combines their two birth signs, and the record was promoted as their attempt at finding the common ground between two individuals whose differences – of temperament, of character, of physical and visual expression, of musical motivation – were becoming ever more pronounced. Five years later, those differences had ceased being things that needed to be fitted together for public consumption and were being touted as selling points to be celebrated and commercially exploited: as if the yin and the yang were spinning so fast that, for their essential balance to be retained, the only way forward was to move together separately but in unison. Speakerboxxx/The Love Below was, in effect, presented as an OutKast album in name only: the two CDs/four LPs comprised Big Boi and Andre albums released in the same package, the bonds between them apparently reduced to a couple of featured collaborations on each other’s solo debuts. The truth, though, was far more complicated.

"The Player" and "The Poet" – as the stickers on the cover of Aquemini put it – were more similar than their apparently diverging public images suggested. Neither of them had the monopoly on any of the elements that fuelled their collective creativity – something that Speakerboxxx/The Love Below emphasises, even as the record celebrates and highlights some of their differences. Big Boi, supposedly the earthier and more streetwise of the two, who bred pitbulls and had a strip club in his basement, was the one whose half of the album included overtly, outspokenly political material and who, in interviews, was keen to talk about how much he adored the music of that least-heralded of rap muses, Kate Bush. Andre, ostensibly the more spiritual and ethereal, whose public apology to the mother of his former partner had been mined to create the group’s biggest worldwide hit (on the cover of which he wore an ankle-length vintage dress over a pair of blue jeans), peppered The Love Below with unreconstructed loverman lines and turned an already uncommonly commercially successful group into global superstars with ‘Hey Ya!’, a track that, he said, confused many of his circle by foregrounding hitherto unexplored 60s pop influences.

"We’re both all of that," was Big Boi’s explanation of how the pair’s individualities combined within the partnership. In an interview conducted a few weeks before Speakerboxxx/The Love Below was released, he explained that each apparent point of contrast would often indicate a shared characteristic which made the individuals particularly well suited to working together, even if these made their partnership harder to understand from the outside.

"Don’t judge a book by its cover", he said. "Just because I might have on jeans and a T-shirt or something like that, man, that don’t mean shit. You’ve got to get to know me. With this record motherfuckers are gonna know what Big Boi is about, they’re gonna know what Dre is all about, and they’re gonna have a clear picture of what we do. You can’t really put it in one category – we do all of that. We’re alike at the same time, but what makes us unique are the differences, and that shit just meshes together."

They had made their debut while still at school, a pair of "knuckleheads", according to Dre, who had bonded over their idiosyncrasies – their divergent traits something each respected and admired about the other because they helped them stand apart from their peers. What they saw in each other, in effect, was a fellow iconoclast; another individual. The name they chose for their group was a deliberate reflection of how they felt set apart from schoolfriends and neighbours as much as intending to stress that being from Atlanta automatically meant they’d be considered as separate to and different from the vast majority of rap acts who, at that stage of the music’s evolution, came from New York or California. Their second album, released in 1996, found them doubling down on their outsider status, recasting them as ATLiens, but it also reflected some growing divergences between the pair – by then, Andre had largely given up drink and drugs and stopped eating meat, while Big was still living a more stereotypical southern B-boy lifestyle. Musically, on the first album they had essentially been vocalists, writing and performing on top of tracks made by their mentors in the production team Organized Noize: on the follow-up, they’d had more control and were credited as producers on four of the 15 songs. By Aquemini, the pair – along with Mr DJ, their on-stage turntablist – were making all the production decisions, though Organized supplied four tracks and the sessions still relied on the extended family of Atlanta musicians who Organized had worked with for years. Inside their most cohesive and contented-sounding collection of tracks, Andre and Big Boi set about finding something fresh, potent and definitive in their apparent differences.

"Aquarius, Big Boi; Gemini, myself – we were trying to show that bridge, that it could work," Andre told me, the same day Big Boi did his separate interview in 2003. "Aquemini was about bringing two totally different things together, because after ATLiens I was kinda feeling like I wasn’t liking music as much. I get really bored fast. My personality… I have to stay excited about something or I give up on it really quick, so I have to find ways to excite myself. And that’s when the drastic change came."

What, I asked, was that change? What were the key elements in it?

"Living out the music," he said. "Like, totally being involved in it. If I’m listening to a song and it sounds like it could be a Broadway play, you want to look like that. I think images were really important. People started to buy… They wasn’t just buying the album, they was buying the whole thought, the whole lifestyle."

And, if that was what they were buying, what was it you were selling to them?

"Freedom," he said, without hesitation. "Freedom of thought – whatever you wanna do. What’s more important than looking just at [Aquemini], you’ve got to look at all the other albums that were out by different artists at the time, so you can understand why this was done. Most of the music that we make, it’s a reaction to what’s going on – it’s a reaction to a void that has to be filled. People think ‘OutKast just make crazy music,’ or some shit like that, but if everybody was makin’ crazy music OutKast would probably make the simplest shit in the world. It comes from, ‘I need to hear this right now. I’m sick o’ hearin’ this type of music, I’m sick o’ hearin’ this type of sound running the whole radio’. I don’t remember anything specific that was out at the time, but I just remember hip-hop and emceein’ had turned into just holdin’ your dick and walking across the stage. It had no style or nothin’ at all. So this was a reaction to that. It had no style, so you exaggerate your style."

The explanation of that combination – taking an approach to making music that is unshackled by expectations or considerations of how the results might be received, and turning the dial up on what makes you different so as to better emphasise the gulf between what you do and what constitutes business as normal in your line of work – provides as fine a distillation as we’re ever likely to get of what made Aquemini so special. In stylistic or formal terms it appears to follow the template established by Southernplayalisticadillacmuzic, combining live instruments and traditional musical composition with an approach to lyric-writing and song construction that relishes the freedom OutKast had given themselves permission to use. But it also folds in the greater sense of possibility that ATLiens afforded, and becomes more than the sum of its predecessors’ parts. To take just one of the more obviously striking examples that 25 years’ distance offers, consider how few people in hip hop were thinking, in 1998, about what role reggae might have to play in the evolution of their art form, about how rap could just be talking over music; then take a listen to ‘SpottieOttieDopaliscious’ – and note that the ripples it caused when it splashed down in 98 were ones that were still strong enough in 2016 to cause Diplo and Beyonce to base ‘All Night’ on it, and for it to be among one of the more striking and acclaimed tracks from one of the most striking and acclaimed albums of deep into the next century.

Between these two albums, at the midpoint between those two extremes, the group released Stankonia, the record that cemented their status in the U.S. but brought them to mainstream prominence worldwide. For all that Andre talks of Aquemini being "the bridge" between their beginnings and their artistic maturity, Stankonia seems to provide the seamless transition from the smoother sounds and traditional approach of the first three albums to the amped-up eclecticism that was to follow. Although it was ‘Ms Jackson’ that provided the international hit that put Dre and Big on the global pop map, the key track on the fourth album is ‘B.O.B.’, which draws from Aquemini thematically and points to Speakerboxxx/The Love Below‘s lead single, ‘Ghettomusick’, sonically. (And, while ‘Ghettomusick’ appears on Speakerboxxx, it was one of the tracks on the split project where the pair worked together; Andre cited it and ‘B.O.B.’ as among the OutKast tracks where the music was largely his creation, with the collaboration coming after

production of the track was nearly complete.)

On Aquemini, ‘Rosa Parks’ showed OutKast’s willingness to draw disparate imagery together to make a statement resonate in powerful and unexpected ways. The song doesn’t mention or directly reference the titular activist’s singular and iconic act of protest, but uses her moment in the civil-rights spotlight as a metaphor to talk about the importance of pushing against restrictions and upending imposed conventions. "It was basically a bragadocious hip hop song," Andre explained. "It was saying, ‘Everybody else, move out the way. Hush all this fuss, everything – everybody, all of y’all, move to the back of the bus.’ It had nothing to do with Rosa Parks – it was just a new symbolism. It was another way of saying ‘Get out of my way.’"

On ‘B.O.B.’ the band did the same thing again, with those "bombs over Baghdad" being nothing to do with the continuing imposition by the Clinton and Blair governments of no-fly zones over Iraq (ongoing at the time the song was written and recorded; the specific period that perhaps gave the band the idea may well have been Operation Desert Fox, a four-day USAF/RAF bombing campaign against Iraqi weapons research and development infrastructure in December 1998) but as a unique, stylised way of repeating one of the oldest exhortations in the hip hop lexicon: don’t front. "It was a connotation for music – it had nothing to do with the war, really. It was symbolism", Andre confirmed. "What I took, what ran round my head, was the idea that they were firing warning shots. I felt that’s what people in music were doing. Everybody was kind of like playing around, too easy and too calm and all that type of stuff. At that time it was about, ‘We all playas, and we in the club with the champagne.’ Everything was smooth, everybody was like cool, and I was ‘No, nah, it ain’t there.’ So it was a reaction to that. I wanted to hear something fierce, and urgent. ‘Bombs Over Baghdad’ was really like a slap in the face, [to] kind of wake everybody up. It was, ‘Don’t pull your thang out unless you came to bang’ – Hey, don’t get in the ring, don’t do this, unless you want to do it."

There’s never a bad time to listen to these records, never a good reason to deny yourself the insight, the energy and the pleasure of immersing (or re-immersing) yourself in these amazing LPs. The current reissues are certainly a fine enough excuse – and will prove simultaneously exciting and frustrating for fans keen to own fresh, clean copies of Aquemini and SB/TLB on vinyl. Both reissues are being made available via hip hop specialist Get On Down, whose website allows UK- or European-based fans to buy in their own currency but adds a hefty additional price tag for posting these notably heavyweight packages from the US. (Someone wishing to buy both releases, and have them sent in the same package to an address in England, will be charged £39.28 for postage.) The newer album is relatively easy to find in European record shops in a 180g black-vinyl four-LP pressing from 2017 retailing for about £40, and it is unclear whether the late-November Get On Down reissue is being pressed from new lacquers or just re-using the same ones as the latest pressings – in which case, the extra money would only be getting you grey and cream coloured vinyl (referred to by the label and the retailer as platinum and pearl). The Aquemini reissue looks beautiful – the three LPs pressed on cloudy pink, green and gold vinyl, with an OBI strip replacing the sticker. But, as far as tQ can establish (at the time this piece was written, we’ve not yet got hold of one), this version is a repress of the 2009 and 2014 US reissues – not, sadly, the warmer, more rounded, more organic-sounding original US pressing. To these ears, despite age-accumulated pops and clicks, the original provides a far more engaging and involving listening experience – as if the music was a living thing, hugging you in its voluminous curves and luxuriant folds. The reissue is still pretty good, but feels a bit more strait-laced: as if the different instruments were limited to operating only within strictly delineated spaces inside the mix, rather than being free to spread out and find their own comfortable space with minimal restrictions. Perhaps the original lacquers were used so much that a new copy of the original can’t be pressed today; perhaps, during the quarter-century since they were made, they’ve been damaged or lost. Either way, by the time a UK-based buyer has factored in the postage costs from a US retailer, you’re almost paying the same as for a second-hand VG+ copy of the original. Yet perhaps the fact that this pair of reissues raise as many questions as they answer is, in its way, a fitting tribute to this most questing and confounding of hip-hop partnerships.