When I was asked to write the liner notes for the new Kirsty MacColl box set, a 161-track celebration of her work, it struck me that only two things crop up when she’s usually mentioned. The first is her peerless vocal, all guts, grit and tenderness, on The Pogues’ ‘Fairytale Of New York’. The second doesn’t speak of her life.

Between 1979 and 2000, Kirsty MacColl showed us her life through her music as a singer, instrumentalist, lyricist, arranger, producer, solo artist and collaborator of real depth, full of dynamism, insane amounts of ability and range. Even before we get to her own music, she was in a bluesy punk band, the Drug Addix, co-wrote songs for Frida from ABBA, sang backing vocals for The Smiths, Happy Mondays, and Talking Heads (she’s in their video to ‘(Nothing But) Flowers’) and sequenced the tracks for U2’s The Joshua Tree (“She gave the album a beginning, a middle and an end,” her ex-husband Steve Lillywhite confirmed to me. “She had these huge reserves of talent.”)

She also wrote songs that launched artists’ careers in other countries (Tracey Ullman’s version of Kirsty’s ‘They Don’t Know’ was a top 10 US hit, becoming a springboard for her becoming a personality, which led to an award-winning chat show), and interpreted songs by other people so well they felt like her own (The Kinks’ ‘Days’, Billy Bragg’s ‘A New England’). Music royalty like Johnny Marr and The Hollies’ Graham Gouldman counted her among the best songwriters they’d ever worked with, although not being a man, she never got the same kind of coverage. She could turn her hand brilliantly to country, folk, jazz, trip hop, synth pop, girl group-doused dream pop, tropicalia, mambo, British kitchen-sink miniatures, epic balladry, and much more.

But in those 21 years, I was surprised to learn that she only released 21 singles and five albums. Granted, she took time off to be a parent (having two sons, Jamie and Louis, with her husband of ten years from 1984, producer Steve Lillywhite) but she was never really not making music. She made so much more material.

As I worked on the box set with Universal’s Michael Mulligan, for whom this was a labour of love, I found out about the demos which had been forgotten, the singles that went unsupported, the entire album left unreleased (which also notably featured Hans Zimmer on keyboards). Many of these showcased the work of an artist with a unique, acute eye for observational detail, nuance and character. Many songs foregrounded women’s experiences. Many were forged through strong friendships with male collaborators, but most also faced obstacles and barriers created by men.

These had been there from the beginning. The effect of Kirsty’s father, the folk musician Ewan, who drifted in and out of her life as a child, persisted; against him, she wanted to rebel at the same time as she wanted to impress him. (When she played him 1989’s Kite, released earlier in the year that he died, he asked to read the “text” and turned the album down, before saying, ‘Very good, Kirsty. That’s the best thing I’ve ever heard you do”. She was pleased, Lillywhite said: “We all need parental acceptance”.)

She had personality clashes with stiffs on the punk scene, major label moguls who didn’t know how to market her, and had relationships with men that faltered until the last one, with James Knight (who I also interviewed for the box set). But I also discovered, from reading her mother’s biography and ploughing through interviews in print and on screen, that Kirsty had been driven from childhood. Struggling with severe asthma as a child that kept her out of mainstream schooling, she had written to Arthur Ransome’s publishers after he died offering to finish his sequel to Swallows And Amazons. She was seven. Later, she sat English language and literature exams two years early; learned the oboe and violin while falling in love with pop records in her mother’s snug. She liked paying attention to lyrics, especially disliking songs in which women sang about their lives being over if they didn’t have a man.

This box set, I quickly realised, would be a testament to the talent of a woman who wouldn’t compromise, but also an industry that wouldn’t compromise.

‘They Don’t Know’ was Kirsty’s debut single, released in June 1979. A song about a teenage girl staying with a boy that other people thought was unsuitable, its sweet, girl group flavour had a more nuanced undertone, one which suggested the uncertainties of youth, while underlining the early quality of her songwriting: “You’ve been around for such a long time now/ Or maybe I could leave you, but I don’t know how”. It also featured MacColl layering her harmonies, a sound she’d been fascinated with since loving the Beach Boys as a child. Lillywhite told me she had brilliant skills as a producer, knowing how to use “her voice to create a sense of atmospherics, almost like a synthesiser”, something she also added to the chorus of Alison Moyet’s ‘Wishing You Were Here’, featured on the collaborators’ disc of this set. Moyet referred to Kirsty, simply, as “Elysian chorus”.

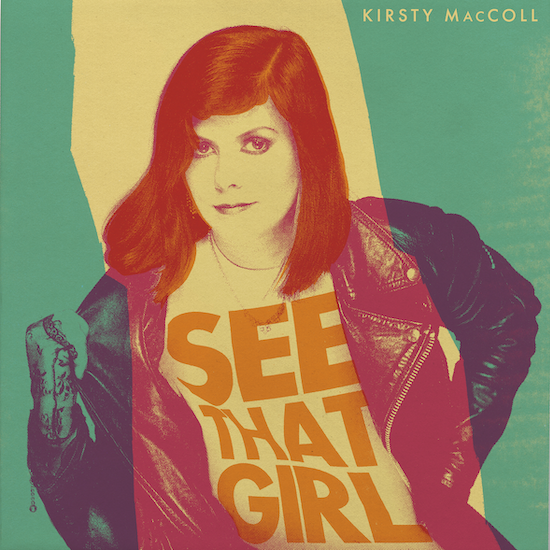

You can also hear Kirsty’s backing vocals on Tracey Ullman’s hit version of her song: Ullman confirmed to me she couldn’t reach‘ They Don’t Know’’s highest note, so its writer came in to hit a beautiful, high note –“baby!” – after the bridge. But while Kirsty’s original got airplay quickly, it flopped, as did her next singles ‘See That Girl’ and ‘You Still Believe In Me’. So did their accompanying debut album, Desperate Character, a perky mixture of originals, co-writes and 60s covers, showing Kirsty’s facility with different pop genres.

Her early co-writer Lu Edmonds, now of Public Image Ltd and the Mekons, told me labels weren’t sure what to do with her back then, especially after her 1981 hit, ‘There’s A Man Works Down The Chip Shop Swears He’s Elvis’. "I don’t think anyone really understood what a talent she was. ‘Chip Shop’ wasn’t what she was really about. She had this super talent of writing songs from so many perspectives, but there was an expectation of her to put together another novelty pop song as they thought of it.”

In her early press shots for Stiff, you imagine them wanting her to be a British take on Rachel Sweet, the 16-year-old with whom they had success with a cover of Carla Thomas’ 1966 hit, ‘B-A-B-Y’. But Kirsty refused to bend to record companies’ expectations of women. Her mother. Jean Newlove, told the Guardian in 2012 that her daughter had insisted on making her own decisions from an early age, and always refused to have her career directed by men, so often switched between record labels as a consequence.

Then came Real, an album influenced by the synth pop of the early 1980s. Its engineer, Philip Bodger, later a producer for Cathy Dennis, remembered: “She was in slightly uncharted territory as an artist between labels, but she was enjoying that period with synth pop being on the rise, and was a real creative force, driving everything herself.” It includes the pulsing, energetic ‘Time’, two songs that mesh textures together in a way that recalls softer moments of early Talk Talk (‘Up The Grey Stairs’, and the sweet ‘Lullaby For Ezra’, with lyrics inspired by a friend’s baby) and a slinky opener, ‘Bad Dreams’, a Human League-style hit in another universe, complete with razor-sharp lyrics (“I dreamed I was standing in Croydon again/ With my life on the line being chased by some men/ My affection’s just a token, and the rewind switch is broken”). Nobody picked it up. It sounds glorious forty years on.

Some success came with 1989’s Kite (top 40) and 1991’s Electric Landlady (top 20); nevertheless, she was dropped from Virgin in 1992 when the label was sold to EMI. She and Lillywhite were also in the last years of their relationship, but her next LP Titanic Days, still swirls with some of her most beautiful songs. ‘Soho Square’ and ‘The Last Day of Summer’ are studies in deep melancholy; ‘Big Boy On A Saturday Night’ shows Kirsty’s raging power; the soft house beats of ‘Angel’ and ‘Just Woke Up’ show how easily she could absorb the sounds of the times.

She also taught herself Spanish and Portuguese before making her 2000 album, Tropical Brainstorm, inspired by her lifelong love of the music of Cuba and Latin and South America. Its second single, ‘In These Shoes’, has since been covered by Bette Midler, Hazel O’Connor and Camille O’Sullivan; its third, ’ England 2 Colombia 0’, is a highpoint for English pop humour, and a savage takedown of adultery.“I didn’t want to try and fail at being the Buena Vista Social Club,” she said of the way her album blended global influences with her voice. “I wanted to succeed at being Kirsty MacColl.”

Digging through Kirsty’s archives, you see how she was happy to present herself simply, without unnecessary glossy nonsense. In 1985 when she had a no. 7 hit with ‘A New England’, she wasn’t slapping on the shoulder pads or Elnetting her hair for video: she was two months away from having her first child, wandering around London in a big coat. “It was a good video,” she said later, adding, “It’s pretty hard getting changed in a toilet cubicle when you’re seven months pregnant.”

She sounds at ease on 1991’s ‘Walking Down Madison’, a track she wrote with Johnny Marr, whose landlady she’d been in the late 1980s when he lived in her old flat. He’d sent her some music to seek her opinion, and she decided to write over it herself. “She thought pop music was the greatest thing,” Johnny Marr said to me in an email. “To her, it should be moving, and clever… elevated almost. She was so good with words and what she loved she loved with a passion.”

The endorsements she had for her 1995 anthology, Galore, further show how revered she was. Bono called her “the Noëlle Coward of her generation”. “When you hear these songs of Kirsty’s, you’re going to want to hang out with her, too,” said Chris Frantz and Tiny Weymouth. Such endorsements didn’t lead to investment, support or bigger commercial success. Some would say she wasn’t prepared to polish herself to fit other people’s specifications. I’d say many of her male counterparts didn’t have to. She could have been someone, but so could anyone – and Kirsty wanted to be herself.

In October 2023, we can soak ourselves in this vast set of songs, remembering how good she was. Try ‘Free World’’s spirit of political protest, or the snappy repartee on ‘Fifteen Minutes’, full of lyrics that the likes of Randy Newman and Lily Allen would die for. Among the forty-seven unreleased tracks, enjoy her brilliant 1992 Glastonbury set, a Croydon-flavoured cover of ‘Eu Só Quero Un Xodó,’ and the session of ‘Soho Square’ for Greater London Radio that makes my heart truly ache.

‘Fairytale of New York’ will always be there. So will the shape of Kirsty’s time on this planet. But this music, like the best music, also feels like it is living and breathing right now, staying true to itself, staying right here.

Kirsty MacColl – See That Girl 1979-2000 is released by UMR tomorrow