For centuries, London has played the role of enabler, but also seducer and corrupter, of the young in search of liberation, work, love, fame or fortune. The delicious anonymity of ancient, uncaring streets is a place where a transaction of self-reinvention might take place, where innocence is traded for risk, the sensitivity of childhood for a rougher arrogance that masks our insecurities. This is the dialogue between city and self that Patrick Wolf turned into his remarkable 2003 album ,Lycanthropy, a record that, given the soaring rents and corporate lifestylification of the capital, might just be one of the final documents of the life of a misfit disappearing hopefully, naively, into the bright lights.

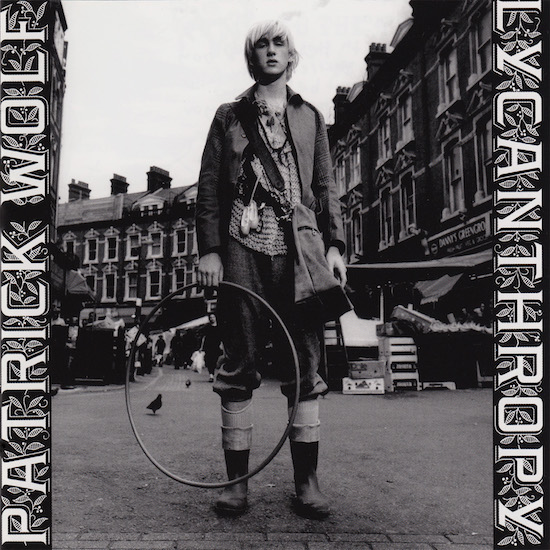

The boy Patrick Apps started writing much of this record in the chaotic years of puberty, when by day he was the victim of school bullies, and by night hung around with Leigh Bowery’s art troupe Minty, London (and, for a while, Paris) becoming zones of escape and creativity. It was at that time he adopted the Wolf persona, in part to create a layer of protection but perhaps also because he wasn’t yet ready to become a man, whatever that meant back in the doldrums around the turn of the millennium. In interviews around the time of Lycanthropy’s release in 2003, he described many of the songs as being a dialogue between his nineteen and twelve-year-old selves. You can sense that in the heady derangement that sounds like puberty, the urgent precocity as audible in the startling collision of musical styles as it was visible in Wolf’s shock of bleached blond hair above dark eyebrows. If Patrick Wolf was the identity he took on in that time of transition, then London was the midwife who shaped it. Together they birthed these fourteen songs, many awkward and painful creatures that capture so explicitly the trials, not a rosy nostalgic glow, of his coming of age. It’s a record as a spell to shudder off the bullies, the authority figures, the conventional life mapped out.

This tumult of both adolescence and trying to survive in London is reflected in how Lycanthropy lurches between tender, slower material of loss and regret to exuberant self-confidence. In terms of the capital, ‘London’ begins with a Westminster chime, looped and then echoed on a piano as a louche rhythm contrasts with melancholy viola. It’s the city as a violent playground of “car jackers and bullet showers / a yellow sign / too many fools in power”. ‘Pigeon Song’ makes the loss of the young self against the urban backdrop more explicit, using the melody of Mary Poppins’ ‘Feed The Birds’ in a graceful folk lament – “London did you have to take my child away/ you buried him under rent and low pay”. These quiet, reflective moments, of “going alone to the cinema”, talking to pigeons, an understanding of something childlike slipping away are brushed aside in favour of the more heady and sensual distractions to be found when sunlight dissolves into the glow from tens of millions of streetlamps and windows. ‘Don’t Say No’ is a murky 4/4 with fizzing static and a determination to immolate self-doubt and then dive in to life’s possibilities, no matter how dangerous: “if you’re brave enough you’ll just let it happen / if you’re brave enough you’ll just succumb”. It’s an acknowledgement that the pleasure of the city can come in being annihilated by it. The song ends with a couple distorted lines from the plague poem ‘Oranges & Lemons’, "atishoo atishoo we all fall down". ‘Bloodbeat’, built from glitch and an infectious repeated melody, becomes a moody banger in celebration of the city’s more murky attractions – “No need for comfort / No need for light / hunting down demons tonight / Eat the terror, lick the spark”.

It strikes me that this hunger for London is often one expressed most eloquently by queer musicians, most notably in Bronski Beat’s ‘Smalltown Boy’ or tracks from Pet Shop Boys’ first few albums, such as ‘King’s Cross’, and certainly present in Suede’s more sexually ambiguous quest for “the love and poison” of the capital. Lycanthropy fits into this tradition, a record not just about youth, but how difficult it is to progress over the threshold to adulthood when you’re deeply conscious of not fitting into conventional sexuality or expectations of masculinity. Part of the appeal of London for me in the late 90s, slightly older than Patrick Wolf but no less wide-eyed and unready, was a sense that my twinkish self simply couldn’t survive anywhere else in this brusque, boorish country. I wanted London, as much as anything else, as a place where I could work out who I was both as a man, or person, and sexually. The city at night, its parks and tree-shaded, scrubby squares as much as nightclubs, offered a sanctuary in which to explore both, but like many others I knew this was a bargain in which I had to give up a part of myself. I was ready to kneel before London, and whoever she brought my way.

It’s why Lycanthropy hit me so hard when I first encountered it, why I would go and watch Patrick Wolf play live whenever I could, in London and beyond, always anonymous and alone within a crowd of people who seemed to be passing through a similar questing time of life. We weren’t quite as bold as him, of course, worked in offices and had sensible clothes, but that’s the thing about the pop stars who mean the most – they possess that piece of you that’s so familiar, but take it somewhere just out of reach, often at such cost to themselves. These days, my inbox might be full of records being marketed using the various letters of LGBTQI+, but back in 2003 Wolf’s refusal of gender in the title track were like nothing else: “I was once a boy / ‘Til I cut my penis off / And I grew a hairy skull / Of stubborn fire / Then I was a girl / ‘Til I sewed my hole up / And I grew a hairy heart / Of dark desire.” This was the era when The Strokes, The Libertines, The Vines (Christ alive) and Razorlight were on the rise, soon to be joined by the Arctic Monkeys in heralding the return of the indie lad. The machismo of nu-metal was still knocking around, queer rap far in the future. Patrick Wolf spoke to boys like me like nobody else.

There was one song, at the heart of the album, that made this especially acute. When I first heard ‘The Childcatcher’ it was a punch to the chest, crunching breakbeats and squirling, lo-fi keyboards under Wolf’s most panicked vocal on the record, gasping, throaty. It breaks down into a jaunty recorder part, like Michael Nyman at his early music time travelling best, creaking electronics and chaos. “I gave you what I had between my legs,” Wolf half-sings, half-speaks in an ogrish growl, “you held me down and said ‘I’m gonna be your right of passage, so boy you better spread, spread ‘em’”. It was the first time I had heard someone articulate experiences I’d had as a teenager at the hands of predatory older men, and over the years the song became a channel that allowed me to delve into that hurt and shame and find a way through it with writing my first book Out Of The Woods.

It’s this visceral willingness to go into the rough physicality of masculine frailty and sex that makes Lycanthropy more than your typical ode to being young in the city. It’s odd that in some ways it would fit right in with our contemporary vogue for art that is at once confessional and a means of exploring trauma, yet feels messier than is allowed now, more brutal, more abrasive. Wolves, after all, have eyes that glow with hunger, and snap and snarl with bloodied jaws. As Patrick Wolf raged against his abuser, “I wrote your name in my shit across the town”.

Listening back, twenty years on, it’s these jarring moods and refusal to be bound by form that means Lycanthropy still sounds remarkably fresh compared to nearly anything else released in the same year. With the Sugababes, Girls Aloud, Justin Timberlake all at the peak of their powers, this was a vintage era for mainstream pop, but Patrick Wolf was too odd even to be allowed to gather the crumbs from under their table. Back then, you can still see records slotting into their easy niches and genres. Patrick Wolf was lazily described as folktronica, despite having nothing in common with other artists in that particular niche save the rather obvious descriptor that he did indeed mix together folk and electronica. In spirit, it is perhaps the best soundtrack I have to the memory of my own musical boundaries dissolving alongside the personal ones, of discovering the heady sexuality of electroclash and being on permanent warnings at various crap jobs thanks to 4am nightbuses home from dancefloors and the other places in which we got up to no good.

You can comfortably listen to Lycanthropy alongside some of the music played in those places, from Peaches to Chicks On Speed, Selfish Cunt, Max Tundra, No Bra, or Simon Bookish, who played recorder on some of Lycanthropy’s tracks, and Kristian Robinson AKA Capitol K, who mixed and released it on his Faith & Industry label. Patrick Wolf himself spoke about the influence of Björk, but this was inspiration working in the best possible way, by osmosis rather than imitation. Lycanthropy sounds nothing like a Björk record, but it inhabits a similar space of invention and confidence in self-expression. Perhaps there’s a similarity in how Wolf uses his very English-accented and honest voice, pushing the intonation, revelling in how it fits the music like awkward limbs pushing into clothing. There is of course a trouble with this when you come up against the mainstream – like Björk, Patrick Wolf was frequently described as an eccentric, an oddball, as if trying to carve out a niche for yourself as both artist and human shouldn’t be trusted. It clearly had a toxic effect, for the story of where Lycanthropy led, and what Patrick Wolf tried to become, is one of the most startling of recent times.

When I interviewed him earlier this year, Patrick Wolf reflected on the bolshy persona he’d created to survive his teenage years and move into his twenties. “On Lycanthropy the motto is: ‘I’ll do this on my own, be your own hero, be your own saviour,’ he told me; “I found out what happens if you apply that logic later on – life ends.” After his debut, 2005’s Wind In The Wires was more cinematic in scope yet a similarly sensitive and inventive record about escape from the city to the coast. Yet from 2007 album The Magic Position onwards it was as if he had given too much to the city and all it represented as the place to find commercial success in an increasingly desperate mainstream music industry that tried to control his fire. It was a grim irony that by trying so hard to become a pop star, Patrick Wolf (for a while) lost what made him such a unique one. He was less lupine and more mothlike, drawn towards the false light of fame, consumed by alcoholism and drug addiction as he did so. He was declared bankrupt after his manager and accountant failed to pay his tax, became creatively unmoored, wrote no new music for years, until a move to the Kent coast and sobriety brought Patrick Wolf back to life.

Happily, his new EP The Night Safari, made using the same instruments and DIY approach as his debut, is almost its equal. When I saw him play at London’s Village Underground recently, it was as if nothing had changed from those early days, aside from the size of the room. A few months shy of his fortieth birthday, Patrick Wolf moved about the stage in homemade clothes, at once commanding and beautifully awkward, just as he always was. The songs of innocence and arrogance that made up Lycanthropy have eventually helped the wolf-boy to become a man, at last on his own terms.