Jean-Luc, CC BY-SA 2.0

All Clear 1980

Personal—eyes only

Tragedy Converted

Into comedy

Indifference

Complete lack of

Task

To be 67 by 1990

To win a revolution

By ignoring everything

Else out of existence

To own personal copy of “Eraserhead.”

—‘Thoughts on the New Decade’, David Bowie, Melody Maker, January 1, 1980

Bowie’s list of predictions for the new year of 1980 suggest a (purposefully) scattered mind: glib, subversive, and slightly at odds with itself. But masquerading behind a playful disregard for the counting of years remained a fierce sense of purpose. Staring down the barrel of the 1980s, David Bowie faced an uncertain future that blurred feelings of optimism with old reflexes of fear and dread. Jumping off from his golden era of music, Bowie had enjoyed a breathless run of eleven studio albums across a ten-year sprint. In the 1970s, Bowie lived by distraction, recording one album ahead before the last one was even released; the further he accelerated forward, the greater the weight of musical history accumulated behind him.

Shifting from struggling singer-songwriter, glam superstar, (plastic) soul man to krautrock crooner and arch-experimentalist, by 1980 Bowie had already lived several lifetimes of creative reinvention. He should have been confident and secure in his career, but his internal critic continued to edge him into a deeper sense of doubt and self-questioning. Bowie would have to draw on new reserves of energy to keep pushing himself onward to relentlessly merge old forms into something different; managing to exist outside of the mainstream while producing a consistent flow of hit singles to support each album. Faced with the great unknown of the imminent new decade, Bowie felt like he was starting all over again.

The 1970s had been a time of political, cultural, and social extremes; many now hoped that leaving behind that difficult decade and arriving into the 1980s would be like looking back to another country, captive in time. Bowie would compare the close of the era to the tumultuous 1920s, a waypoint to mark the beginning of the late twentieth century’s descent toward a long, dark night, suggesting that he was heading toward the divided confusion of the new 1930s. But it was within – or perhaps against – the 1970s that Bowie had come into his own as a catalyst to revolutionise the popular imagination, subverting everyday reality and making transgression his safeguard against forced normality. Still echoing the fallout of Bowie’s most self-destructive phase, Scary Monsters would straddle time, as much an artefact of the 1970s, as an album out of time. For Tony Visconti (2007), “[Scary Monsters] sums up the whole era from Space Oddity; it wasn’t our original intention but we realised that we had ten tracks which were all very commercial, and encapsulated one period or another. Like the title track was back to the Ziggy days, and ‘It’s No Game’ was like a Low kind of feeling.”

From the heights of pop glamour, Scary Monsters soon runs into a downhill trajectory racing towards the very real pressures of modern life to expose the cracks within democratic society. The songs are forceful and urgent, strong-arming the listener to attention; the close-listening experience demands a deep immersion with Bowie whispering pain and despair as much as he screamed self-loathing and horrific outrage, where the race to the top was in fact heralded by a vicious struggle on the way down. Scary Monsters sees Bowie rise up from the ashes of his most confessional music since Low to become the definitive exorcism of his greatest struggles and highest lows.

Bowie’s internal conflict doubled as a reflection of the times: where the distance between desire, dreams, and reality came into stark relief; as dark shapes began to emerge from all corners, new hopes soon coalesced into nightmares. The 1979 election of a new British Conservative government helmed by Margaret Thatcher aimed to overturn the stagnation of the previous prime minister, James Callaghan, and deconstruct the postwar recovery years dominated by the Labour Party. The 1970s had seen Britain slowed by a cycle of strikes, inflation, and power cuts until it began to feel that society was in retrograde. With Shakespearean verve, the period was branded the “Winter of Discontent”.

In the run-up to her general election victory, Margaret Thatcher fed on paranoiac energy, name-dropping dystopian visions made popular by artists and musicians like Bowie. She warned of imminent disaster if a more authoritarian government was not brought into power alongside secret fears of an imminent socialist coup: “When rule of law breaks down, fear takes over … criminals prosper, the men of violence flourish, the nightmare world of A Clockwork Orange becomes reality.”

Speaking in 1977, Bowie described himself as a social observer, but instead of focusing on specific events of the past he tried to capture the energy of the present, his albums merged into a living performance. Having completed the artistic revolution of the Berlin Trilogy, 1979’s Lodger album divided critics and fans between grudging acceptance and deepest adoration. Bowie’s final call on the closing track, ‘Red Money’, unites the album as a grouping of “planned accidents”; where Bowie yelps, “Project cancelled” over angular, convulsive funk-rock, the record is written off as an auto-destructive exercise, another exploding ticket to nowhere, the infectious document that must eat its own words. Chris O’Leary hears Bowie’s natural evasiveness come full circle, devouring its own tail; as the abortion of process becomes its own catharsis revealing Bowie stung by the malaise of the twentieth century’s “nervous disease.” Spiked with fresh uncertainty, Scary Monsters is still tangled up in the same hesitancy and divided struggle of Lodger. According to Greil Marcus (1979), the songs of Lodger “all speak for a future in-the-present in which one must protect oneself from the world, from other people and from one’s own visions, desires and fears,” combining the shock of brute reality and more private internalised horrors.

In his self-enforced American exile and later drifting into mainland Europe, Bowie was largely absent from England for the brief explosion and even shorter fizzling out of punk. Less a movement than a short-term affect, it became a grassroots avant-garde rejection of the body politic still tied to monarchy, church, and state. The Sex Pistols’ cry of “no future” would seem prophetic echoing down the decades; if not entirely fulfilled, it would be met by the true struggle of Thatcherism yet to come.

Bowie emerged blinking into the cold light of 1980 to find a new Britain. The election of a Conservative government seems to be the moment of first blood; death as rebirth, sparking his renewed interest in the growing discord reflected across society: “Scary Monsters always felt like some kind of purge," Bowie said in an interview with Bill Demain from 2003. "It was this sense of: ‘Wow, you can borrow the luggage of the past; you can amalgamate it with things that you’ve conceived could be in the future and you can set it in the now’”. This fed directly into Bowie’s continued fascination in post-apocalyptic scenarios, always jumping the gun to the greatest hits of the worst-case scenario –even Ziggy Stardust’s good time rolling in 1972 kicked-off with doom and gloom of ‘Five Years’.

From his review of Lodger, Jon Savage noted “a small projection from present trends, call it Alternative Present if you will,” in Bowie’s music. This granted him the perspective of an advanced future (present) tense, seeing through the everyday atrocity as if with a knowing sense of inevitability. Everything seemed to be running fast-forward, in free fall, accelerating toward the hyperreal technocratic state chained to the conspiracy theories of the military-industrial complex – the hunger for progress driven to a fever pitch at the bleeding edge of now. Viewed through the twisted prism of a thwarted political climate, everywhere Bowie looked, the world seemed full with clear and present dangers of terrorism and foreign conflict – some imagined, others very real – made manifest in the political rhetoric of Reagan’s “evil empires” and Thatcher’s “enemy within.” This weaponized language provided just cause for witch hunts to root-out the freaks, radicals, and rebels on the domestic front, to normalize the notion “war all the time” against one common (invisible) enemy after another – all for the preservation of Western conservative supremacy. Scary Monsters is infused with the same spirit of paranoiac doom-ridden rhetoric chattered among the political classes and echoed throughout sustained media bombardments; Bowie’s lyrics are flush with violence, broken bones, and damaged lives cut short. Where before Bowie had heard warning shots fired overhead, they now rained down as friendly fire from loose cannons and assassins, all with the deadly intent of the sniper picking off undesirables.

Where so many people’s inner lives hinged on daily uncertainties, the songs of Scary Monsters find Bowie setting himself against an unhinged global picture. His lyric notes express burning ambiguity mired in contradiction; for once, Bowie seems afraid to make the first move: “Half of me freezing, half of me boiling, I’m nowhere in between,” as Bowie seemed to write compulsively across his lyrical sketch sheets: “A reactive person … too much data, possible events.” Chris O’Leary hears the album as a singular “horror documentary,” the reel caught in its own teeth; phrases tumble out of him, spooling endlessly, turned over and over in a frantic mind as if overhearing oneself from another room: a wild terror, fresh heartbreak, psychic collapse.

Tired of occupying his station as the permanent outsider looking in, passing commentary on a planet that in many ways had always seemed alien and foreign to him, Bowie discovered a newfound need to reconnect with other people, though still focusing on himself as an introspective subject. Chris O’Leary noted that the David Bowie of 1980, whether by accident or design, found himself most at home in a “society of one.” The rising atomisation of the individual remained at the heart of Bowie’s music for several albums, charting humanity’s widening separation from common cause. In 1997, Bowie observed of himself, “Thematically I’ve always dealt with alienation and isolation in everything I’ve written.” Putting himself into the mind-set of loneliness as a place to write from, where small universes bloomed inside the mind, this act of self-distancing would increasingly become a mutual splintering disconnect. As Bowie watched the real-time heat-death of common mutuality, it seemed to confirm that alienation was simply a new expression of freedom (from others), so worldly concerns became centred around transactional analysis, individuals weighing the needs of their own lives against the invisible many. The decline of the nuclear family, rising divorce rates, and the carve-up of land and homes into ‘real estate’ spoke to private interest trumping collective responsibility, with each Englishman raising the drawbridge of his or her own castle. This confirmed the entitlement of a round-waisted petit bourgeois middle class, championing the climbing of the social ladder and the accumulation of “new” money to escape their past and avoid working-class associations, kicking the rungs out beneath them as they strained to climb ever higher.

Writer and journalist Jon Savage, who began as a music fan and became the man-on-the-ground chronicler of punk, noted the perilous times of 1980 in which Bowie had arrived. Still popular, it was as the glam rock entertainer that mainstream audiences and casual radio listeners valued him most. But now even his most outlandish tendencies had been absorbed into the new subculture. Bowie was no longer himself; he was “us,” standing at odds with the unsettled mood of the times, while the most radical of new musics that emerged in the brief renaissance of post-punk would gradually become less confrontational, more acceptable, and unthreatening as the decade wore on or remained underground as nonconformist subversion, somehow ruining the party: “In the face of increasing hardship and political polarisation, arty posing and homosex – inextricably linked too often thanks to Bowie’s example – are definitely seen to be out: the former as a childish luxury, the latter as a definite social disadvantage as dog eats dog.”

On Scary Monsters, there is a suppressed rage that mourned, mocked, and sampled the Bowie mythology, dissecting the beautiful corpse, still living. The faint and resigned “woah-ah-oh” line that ushers in the pre-chorus of ‘Ashes to Ashes’ is heard again on Tonight’s ‘Loving the Alien’, reaching strange heights of self-awareness but also managing to sound new and different and standing entirely in its own right. Elsewhere, Bowie blogger Neil Anderson points out that Bowie’s 1999 song ‘Pretty Things Are Going to Hell’ revisited the youthful spring of ‘Oh You Pretty Things!’ like ‘Changes’ in reverse, backward growth that interrogates images of the past. The sheer magnitude of Bowie’s back catalogue meant that he was weighed down by the number of songs and the refraction of images, making Bowie confront his many selves. As Greil Marcus noted, “Right at this point, then – the verge of the 80s – Bowie should be ready for a major new move, or a major synthesis.”

Visconti and Bowie dug in for a longer, more considered recording process: “We decided to give ourselves the luxury to think of every possible thing we could do. That was the premise. And we took ourselves very seriously.” Noting that the role of the producer often required him to make hundreds of creative and technical decisions each day, Visconti points out that Bowie was keen to experiment and discard approaches that weren’t working – more parts were left out than included. The producer would later compare Scary Monsters to the more urgent and vital intensity of the Beatles’ Revolver; thankfully free of the nostalgic whimsy and kitchen-sink drama of Sgt. Pepper’s, it remains a leaner, sharper, and harder record despite having a less focused track listing.

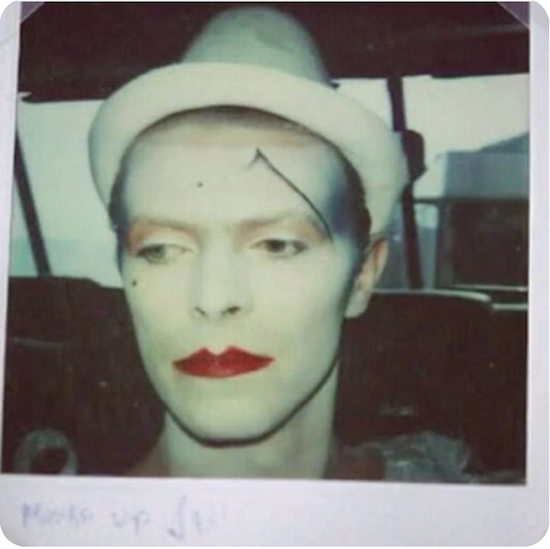

Embodied by the staggering and wayward Pierrot figure of “Ashes to Ashes,” Scary Monsters, shows Bowie trying to regain his balance with no small sense of desperation to keep things contemporary and interesting. Interviewed by Angus MacKinnon for NME in 1980 Bowie presented as a self-confessed outsider working within the music industry to be both blessing and curse, a situation under which he suffered “lacerating self-analysis” demanding constant reexamination divided across zones of past/present/future. Bowie confessed to these deeper anxieties on ‘Teenage Wildlife’, confronted by the rising tide of young hopefuls following in his wake that already threatened to eclipse him as yesterday’s news. MacKinnon noted: “It must have been exhausting to be David Bowie. You could tell that it weighed heavily on him.”

In describing the direction of the new album, Carlos Alomar could have been talking about Let’s Dance: “Scary Monsters was a new awakening," wrote Demain in 2003. "The intention was up-tempo, high-energy songs. It was to hit them right between the eyes.”. The album sits at the peak of Bowie’s most accessible and immediate songwriting: short, sharp songs in praise of pop and rock traditions, pieced together by studio musicians but endlessly adapted and altered by studio production. In the days before digital recording, Bowie and Visconti would reach for better and better takes, knowing that once they had recorded over the last tape, there was no going back, fighting alongside one another for the best of the best. As Tony Visconti put in 2007, “We were pushing the boundaries further than we ever had with this album”.

Silhouettes and Shadows: The Secret History of David Bowie’s Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps) by Adam Steiner is published by Rowman & LIttlefield