The future Tai Shani can see is fleshy. Everything throbs and squirms and palpitates. Everything is pink or blood-red or yellowy (not yellow). It recalls not the gleaming surfaces that still unite Kubrick’s 2001 to the flying saucers of the 50s, nor the rusted chrome that draws Neuromancer close to Star Wars, but something more like the hardware formed of skin and tooth in David Cronenberg’s Existenz or the weird biomedical dystopia of Crimes of the Future. There is a line towards the beginning of Shani’s (2019) book, Our Fatal Magic: “No more concrete, glass, or industry. Just oozy milky rubble that expands slowly and flows down the street.” It could almost be a manifesto for the artist’s work as a whole – and this latest project in particular.

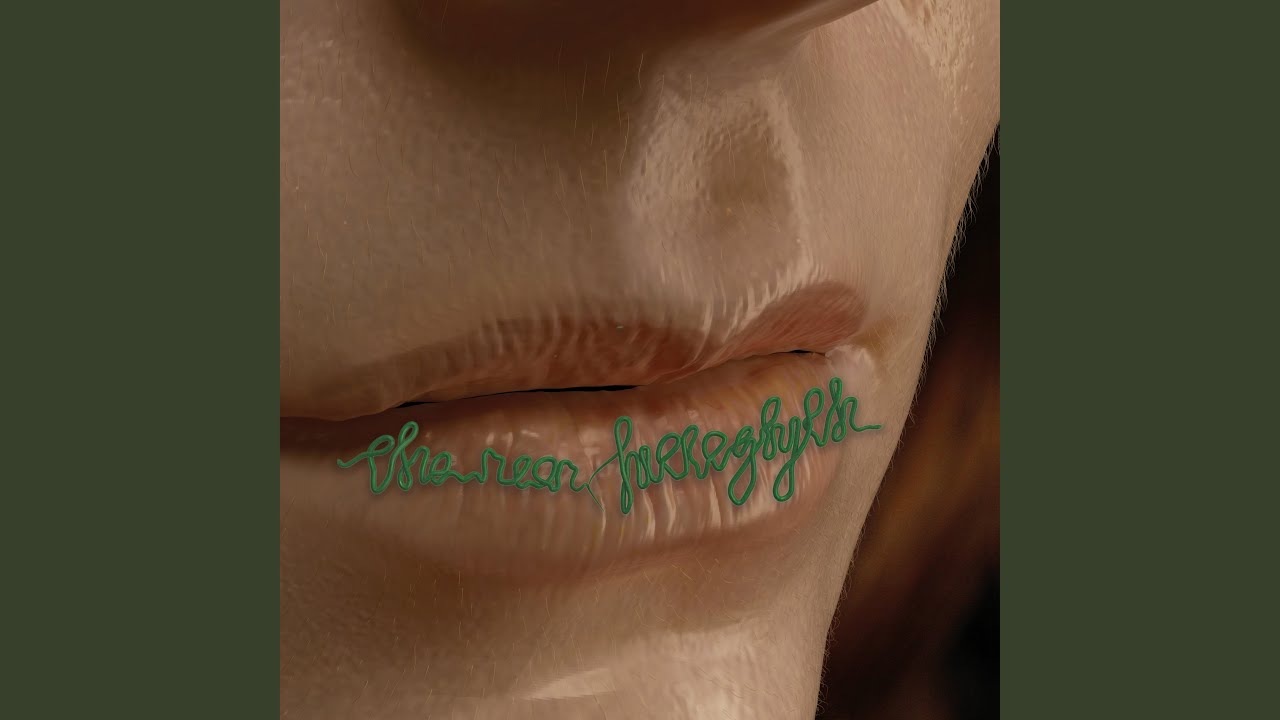

Our own era longs for enchantment. The last several years have produced a succession of attempts to re-appropriate the witchy, the gnostic, and the mystical. Cosey Fanny Tutti’s hymning of Margery Kempe. Huw Lemmey retelling Hildegard of Bingen. Even in a more mainstream context, one could cite Marvel’s hit TV series WandaVision with its girl-bossing of the Salem Witch Trials. Somerset Hourse’s blockbuster group exhibition The Horror Show divided its sprawling mass of stuff into three themes: Monster, Ghost, and Witch. The last featured work by Jesse Darling, Anne Bean, and Linda Stupart, amongst which Shani’s own jesmonite and foam sculpture, also called The Neon Hieroglyph, stood out for its uncanny combination of the playful – almost childlike – and the richly disturbing.

Like Our Fatal Magic before it, the album of The Neon Hieroglyph collects a series of stories, loosely connected and even more loosely narrated. At times, more like dreams than tales. They are not strictly science-fiction, per se. Their settings in time and space range from the mystery cults of Ancient Greece to rural France in the mid-twentieth century. But the prose has the delirious quality that good sci-fi has. And listening to the stories narrated by Molly Moody on this new record from the State 51 Conspiracy, it feels like science fiction. Partly – not only – that is due to the electronic score by Maxwell Sterling, a sinuous, swirling soup of sound in which no timbre recalls any known solid body, and no pitch is ever quite stable. It is music that slurs and squelches, creating its own imaginary spaces and undoing them, erasing and unravelling them, in the same breath.

Shani’s language is already thoroughly musical, full of assonances and sibilances, strange loops and repetitions. Sterling is wise not to try and mickey-mouse that music, aping its own inherent rhythms and melodies. Nor does he simply accompany or cushion the voice, producing ‘unheard melodies’ (to quote the scholar Claudia Gorbman’s term for the supporting role typically played by a Hollywood film’s score). Rather, the electronic sounds here are something more like the sea through which the words swim, sometimes drifting gently beneath, other times rising up and engulfing the voice, drawing it deep down within itself.

If the voice here is already musical, then the music, too, sounds sometimes like a voice – or like a splintered fragment of voice or like many voices combined. There are bits, particularly in the second half of the second side, in Parts Eight and Nine of The Neon Hieroglyph, where these bursting FM soap bubbles start to resemble some artificially stuttered choir or the curiously warped ghosts-of-voices that sometimes emerge from AI generative music projects, where the system has been fed a whole swathe of sounds – acoustic and electronic and everything in between – and asked to make a whole bunch more from a few simple prompts. Like, if this is what music is, make me some more of it – an endless flood of it. It isn’t that the system is itself inhuman or antihuman; simply that the distinction between the human and the non-human is meaningless to it. The human voice is not special to such a system, as it almost inevitably would be to any listening human ears, and so it treats it like any other sound, warping it and recreating it anew. So you get these odd half-voices, human and also not, deep in the uncanny valley.

The Neon Hieroglyph makes its home in that valley, warming its toes at a hearth in which the distinctions between people and other, non-people things start to melt and blur. Spores have desires here, and agency, too – perhaps even the capacity to change history. Ontology is fluid and unstable. Trunk Records once released a compilation of music (and speech!) taken from the free flexi-discs that used to appear taped to the front of pornographic magazines. Breathy voices telling sexy stories over a soundtrack like a louch re-imagining of the Muzak Stimulus Progression programme. If you can imagine for a minute what that CD might have sounded like had those jazz mags been created by and for not human people but instead some vast alien super-intelligence built of microchips and mushrooms, silicon and tree sap, then you’ll come close to the sound and feel of The Neon Hieroglyph. A chitinous bacchanalia. An ars erotica of yeasts and moulds.