John Cheever, one of the great American masters of the short story, wrote ‘Christmas Is A Sad Season For the Poor’ in the late 1940s, as the country was on the brink of a post-war economic boom. Its protagonist is Charlie, an elevator operator in an exclusive uptown Manhattan apartment block who is lonely, hard up and clearly in a funk. It begins:

“Christmas is a sad season. The phrase came to Charlie in an instant” and goes on to describe “an amorphous depression that had troubled him all the previous evening. The sky outside his window was black.” As he encounters the wealthy residents one by one, they choose to lift his ailing spirits with lavish dinners and their unwanted gifts, in what is eventually described as an “avalanche of charity”.

It’s a charming read, but curiously out of kilter with so many stories written by the notoriously tormented Cheever – misanthropic, alcoholic and a closeted bisexual burdened, as his journals attest, by his ‘depth of discouragement’ – and is as if he is carried along by the need for all Christmas tales to have a happy ending.

Anyone who has ever been to New York in December can’t fail to spot that more than any other nation, the USA turns the dial up to eleven when it comes to celebrating the festive season. From the flashing lights and illuminated Santas on the facades of modest homes in Queens to the legendary Rockefeller Centre Christmas Tree – this year an 82ft tall Norway Spruce, 50 feet wide weighing 14 tons – it is, as countless Hallmark greeting cards claim, ‘the season to be jolly’. Ebullience is mandatory.

But forty years ago this Christmas, musicians from New York and Detroit gifted their home country the most extraordinary Yuletide album ever compiled. One that, like Cheever’s elevator operator, was loaded down with financial struggle, loneliness, broken relationships and malaise.

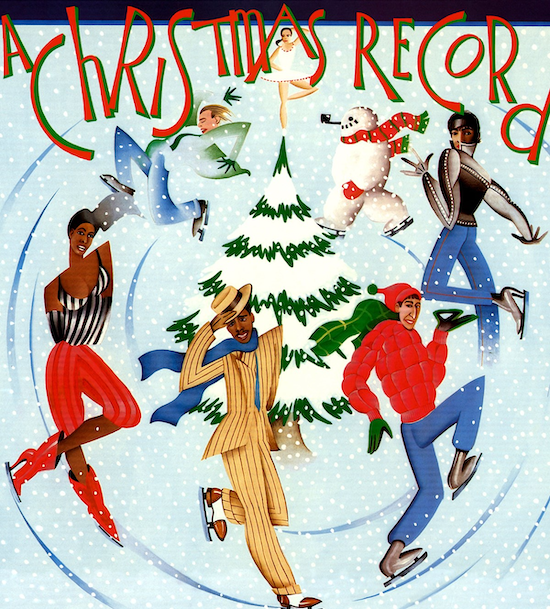

A Christmas Album, featuring the roster of New York’s fashionable-label-of-the-moment, Ze Records, was on the surface as celebratory as any Hallmark Card. On the front cover its stars are painted in bright snowbound colours, merrily skating on an ice rink that could easily be the perennial attraction at the foot of the giant Rockefeller tree. But who’s that chasing a pipe smoking jolly snowman around the ice? Ah yes, it’s Alan Vega, frontman of the electronic duo Suicide whose most notorious song to date was a nihilistic drone about a young father whose struggles to feed his family end with him killing his wife and child before turning the gun on himself. Which begs the question: what’s in that snowman’s pipe?

Ze’s Christmas record had in fact already slipped out in the UK the previous year to limited attention, though the New York Times music critic Robert Palmer, reviewing 1981’s seasonal records, made it top of his list and noted that “it is worth seeking out and worth paying import prices for.” He wondered why the US label bosses had chosen not to give it a domestic release. Could it have been that its fabulously twisted mix of disco and despair was just too raw a commercial prospect in a city – a country – in economic dire straits?

In the year that the album’s songs were being recorded the USA was experiencing the worst economic downturn since the Great Depression. And as the Christmas of 1981 loomed, in the Ze heartland of New York, a strike by the city’s refuse workers resulted in more than 100,000 tons of garbage piling up on city sidewalks. It may not have been intentional, yet one of the more enduring achievements of A Christmas Record is its document as a Yuletide ‘state of the nation ‘.

The album itself was never envisioned as conforming to conventional notions of a Christmas album. In Ze co-founder Michel Esteban’s sleeve notes to a later reissue he gave his rationale behind the project. “I have always thought that the principles of Christmas: family, the tree, gifts, peace in the world etc. were slightly contradictory to a certain vision of Rock & Roll. I found it hard to imagine John Cale and Lou Reed sitting around a Christmas tree exchanging gifts with Nico and tucking into a turkey dinner.” His Christmas record would twist the knife as it carved the turkey.

That said, Esteban also acknowledged its inspiration was the record that the Beach Boys’ Brian Wilson has always claimed his favourite album of all time: A Christmas Gift for You From Phil Spector, the wall of joyful sound that celebrated Frosty The Snowman, Santa Claus and Rudolph the reindeer in truly impeccable style in 1963 and continues to eternally stand as a landmark in seasonal recordings. But ironically Spector’s sleigh bells and perfect harmonies were also launched into an American society in the throes of turmoil. The ‘Flash Crash’ of 1962 saw a huge decline in the US stock market and the post-war age of prosperity under the Presidential term of John F. Kennedy, a leader all too aware that “The Nation is still falling substantially short of its economic potential.”

Spector’s Christmas album was released on November 22, 1963. That morning, JFK was assassinated in Dallas, Texas.

At the start of 1981, Ze had issued a compilation called Mutant Disco, a definitive statement of where New York music was at. Few people could have predicted that they would bookend it at the year’s close with forty minutes or so of Mutant Christmas, the soundtrack to the most bleak Christmas party of the 1980s, the mood less bonhomie than melancholia.

To my mind, the American 1982 release is the definitive version. Here, the tracklisting was altered to great effect. It no longer opened with ‘It’s A Holiday’ by Bill Laswell’s Material and Labelle’s Nona Hendryx, with its funked up riff reminiscent of the Gap Band’s ‘Burn Rubber On Me’. With throwaway lyrics about celebrating in the city, it was the weakest effort of all the Ze artists to contribute. August Darnell’s romantic ‘Christmas On Riverside Drive’ – capturing the spirit of Spector with its nod to “old Jack Frost” and heading to spend Christmas with his sweetheart – was also moved further down the mix.

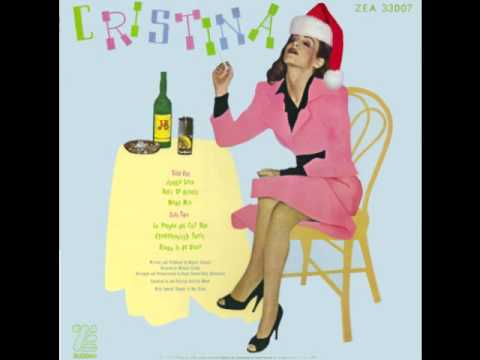

Instead, it begins with the anti-Christmas gem by the jewel in Ze’s crown, Cristina. The first artist to release a record on the label, Cristina – wife of label co-founder Michael Zilkha – was its pre-Madonna, the embodiment of Dorothy Parker if she’d held court at Danceteria instead of the Algonquin Hotel. Smart, acerbic, loquacious and drolly deadpan, Cristina had already caused the label trouble with a cover of the Peggy Lee classic ‘Is That All There Is’, reimagining the lyrics to include references to arson, gay dancers, Quaaludes and an abusive boyfriend, resulting in an injunction from the songwriters Leiber and Stoller.

In ‘Things Fall Apart’ – the title alone so brilliantly anti-Festive – Cristina’s mother has become too ill to reach the top of the tree to hang the angel who has, fittingly, lost a wing.

The song’s protagonist is so broke herself that she has to make do with a cactus decorated with earrings she meant to pawn. Attending a swanky party she notes that “They killed a tree of 97 years / And smothered it in lights and silver tears”. She goes back to her apartment, her boyfriend has dumped her, and in the end she “wept a bit. And fed the cat.” Cristina’s delivery is exceptional, driven along by an almost hair metal guitar riff and Ze’s own version of a ‘wall of sound’.

‘Things Fall Apart’ was produced by the duo recording as Was Not Was, one of whom argued it was perhaps “blasphemous to turn Ze artists loose on Christmas." Their own contribution, ‘Christmas Time In The Motor City’ is set in the barren streets of Detroit – recorded at a time when the state of Michigan had an unemployment rate of seventeen percent, with nearly three-quarters of a million people out of work. With their art-punk-funk style geared up a notch from the Cristina track, they prowl the streets ‘paved with rusted pennies’ before a spoken work breakdown from the point of view of a homeless man sharing a square on Christmas Eve in the park feeding bread to pigeons. Resigned to his lot he seeks refuge in an all-night donut shop where:

“A sad-eyed girl mops the floor next to my feet

The light in here is far too bright

The radio plays ‘Silent Night’

I sit and watch the traffic panic, it sails away

Look at this, it’s Christmas Day.”

Should this suggest A Christmas Record is a tough listen, the truth is that it’s frequently sharp and punchy, with its label’s strain of ‘mutant disco’ running through it, and there’s often a self-awareness to the bleak narratives that’s wicked black humour. On top of which, Davitt Sigerson’s closer, ‘It’s A Big Country’, is the closest you could get to turning a family Christmas greeting into a soft rock classic.

That said, the two outings by Alan Vega and Martin Rev of Suicide are stark electronica as brittle and icy as the rink Vega skates across on the record’s sleeve. Both utilise the same backing track, which sounds as if Kraftwerk’s ‘Neon Lights’ had taken a valium and headed off to Tompkins Square Park to score more. Yet there’s sincerity and despair in Vega’s ‘Elvis in Alphabet City’ vocals and some clinging to hope in a trash-stricken New York. “This year it’s gonna be so different,” he croons. “We ain’t gonna be so broke. No more blues. We’re gonna smile, smile, smile…” Whether conviction or delusion, there’s no doubting this was, for its time, the most hopeless a Christmas song had sounded.

Martin Rev and Alan Vega

But what would any Christmas narrative be without its happy ending? It took some time, but the Ze Christmas Record eventually gave the holiday season one surprising, stone cold classic – the punningly titled ‘Christmas Wrapping’ by The Waitresses. Starting with knowingly cliched sleigh bells straight out of Phil Spector’s mixing desk, it’s carried along on a Chic-inspired bassline swaggeringly played by Tracy Wormworth. Spector himself might have been impressed by its production, where those bells carry on subtly panning from left to right throughout the verses, the double tracked chorus packs a punch, and its saxophone cuts through like a brass bauble gleaming on the tree.

Songwriter Chris Butler had intended to go with the general vibe of Ze’s anti-party, being himself a festive refusenik. “I poured my sourness into this song,” he recalled. “The first words I wrote down were: Bah humbug.” But, much like John Cheever some thirty years or so earlier he couldn’t fight the feelgood fantasy of the classic American Christmas. And thus ‘Christmas Wrapping’ is a great legacy for the late Patty Donahue, as she inhabits the character who doesn’t have the energy to deal with the madness leading up to the big day but still gets “the world’s smallest turkey” from a budget supermarket and then, forgetting the cranberries, bumps into the man of her dreams at the all night grocery. There’s a lot of pathos and indeed social commentary on A Christmas Record but the moment when Donahue sees him and says “You mean you forgot cranberries too?” … well, only the stoniest of hearts would fail to fall for it. Merry Christmas one and all.