It’s 1970 and David Bowie is spinning in a very strange orbit. Last year’s ‘Space Oddity’ seemed to be his lift-off into the pop stratosphere. January comes with a Mirabelle cover, his dreamy eyes and golden locks hurtling towards teen walls. In February, readers vote him Disc And Music Echo’s Brightest Hope, receiving his award he’s resplendent in a double-breasted caramel cord suit at London’s Café Royal, rubbing shoulders with Cliff, Lulu and Cilla. ‘A star shoots upwards,’ proclaims the paper’s pages and when Major Tom’s odyssey scoops an Ivor Novello that May who can disagree? Except March’s follow-up 45, ‘The Prettiest Star’ sinks without trace. A delicately orchestrated love letter to Angela Barnett whom he marries that spring, it features friend-rival Marc Bolan on guitar. It sells less than 800 copies.

There are glimpses of glam rock future. With a band billed as The Hype, Bowie takes to the stage of Camden’s Roundhouse as Rainbow Man. New guitarist Mick Ronson is Gangsterman, Tony Visconti on bass is Hypeman and drummer John Cambridge has become Cowboyman. June brings a remake of last year’s Memory Of A Free Festival, now split in two parts, sprinkled with stardust from Ronson’s Les Paul and Ralph Mace’s Moog, a hippy predecessor to 1972’s ‘Starman’. It flops.

The Hype move into Flat 7, Haddon Hall, 42 Southend Road, Beckenham, Kent, the Bowies’ residence since October 1969 (by April Cambridge will be replaced by another Hullensian, Woody Woodmansey). A mid-Victorian gothic lair in leafy suburbia surrounded by huge gardens, Haddon Hall has a regular visitor, Bowie’s half-brother Terry Burns. Burns’ home is a 30 minute drive away, Croydon’s Cane Hill psychiatric hospital. It’ll find itself on the original cover of ‘The Man Who Sold The World’, looming ominously in the background of Mike Waller’s cowboy comic-strip art. Spurred on by Angie, Bowie acquires Mr Fish dresses, he’ll be captured wearing one reclining on a chaise longue on another sleeve for the record he’ll later describe as ’all family problems and analogies put into science fiction form’.

It’s a haunted house of hard rock and Hammer Horror-folk, monster riffage shreds speakers, ghostly Moogs and Stylophones chill spines in a Magickal Mystery Tour through mythological gay sex, madness, power-hungry computers, Nietzschean supermen and men who aren’t really there at all. Conceived as Bowie and Visconti’s Sergeant Pepper it gathers dust in Mercury’s cupboard, a grand design going nowhere, like the minstrel’s gallery at Haddon Hall.

That August en route to a Hype gig in Leeds, Ronson and Woodmansey view the road signs back to Hull and bolt. Visconti has also vacated Haddon Hall, moving closer to Bolan, distrustful of Tony Defries, who has lured Bowie away from manager Kenneth Pitt. That October’s Visconti-produced ‘Ride A White Swan’ will hits no.2- T. Rexstasy has begun. Having started the year a hippy heartthrob Goldilocks, Bowie has now morphed into a pre-Raphaelite Lauren Bacall with a Garbo pic on the mantelpiece. But he ’s a star with no firmament, a Mad Count with a shrinking dominion…

He strums a new song into a tape recorder. ‘Tired of My Life’ is starkly personal like one of his favourite records that year, Lennon’s Plastic Ono Band (though those overdubbed voices suggest a lush, orchestral Neil Young/ Jack Nitszche-style arrangement). Perhaps it’s too revealing. It’s shelved. Eerily, when a fragment surfaces on Scary Monsters’ glossy mechanical grind via ;It’s No Game;, it comes months before Lennon’s murder. Here in 1970 those lines “put a bullet in my brain and it makes all the papers” come after a decade of political assassinations, and Andy Warhol’s shooting, from a man as wary of fame as he is willing to die for it. It also anticipates the most startling moment in a film he’ll be mesmerized by in 1971’s early weeks, the bullet entering Turner’s head during Performance’s climax.

But, as always, amid the doom and gloom there’s boundless optimism. The Bowies have a baby on the way. He signed a new Chrysalis publishing contract with Bob Grace in October. The £15,000 advance easily covers Haddon Hall’s £14 weekly rent. He’s filled the space left by The Hype with a piano he composes on furiously.

Photo by Brian Ward

David Bowie’s 1971 began with a flurry of activity. On 4 January a demo he’d cut at Radio Luxembourg’s studios was sent to Tom Jones’ management for the singer’s consideration (he never recorded it). ‘How Lucky You Are’ was part Brel chanson, part Brecht/Weill cabaret, a piano-led waltz with a sexist sting just like Jones’ ‘Delilah’. 11 days later ‘Holy Holy’, a funky cauldron of Barrett, Bolan and Bolero, was released. Like everything since ‘Space Oddity’ it failed to chart. Even his most ardent supporters in the press grew doubtful of his future. “Maybe there’s just something about Bowie that doesn’t run alongside the path of luck,” wondered Sounds’ Penny Valentine that year. That March T. Rex’s ‘Hot Love’ began a six -week reign at Number One.

Despite the appearance of a one-hit wonder Bowie was firing on all cylinders. “I forced myself to be a good song writer,’ he said later of this period of prolific, self-sufficient creativity as he toiled away at the ivories, or the 12-string Hagstrom guitar Ken Pitt had given him. Through the “sheer graft” (Bob Grace) came lightning flashes of inspiration, Bowie stumbling from bed to piano at 4am to flesh out ‘Oh! You Pretty Things’. Originally intended for Leon Russell, a Mickie Most produced version for ex-Herman Hermit Peter Noone, issued that March, rose to Number 12. Bowie played piano and snuck onto Top Of The Pops in his Mr Fish dress for Noone’s performance (plugger Anya Wilson had previously been told ‘perverts’ weren’t welcome).

Later that year Noone recorded Bowie’s theme tune for a Rodney Bewes sitcom that never was, ‘Right On Mother’ (Most even floated a Bowie-written Noone concept album). Throughout 1971 he was a potential one-man Brill Building, handing friend Dana Gillespie ‘Andy Warhol’, offering ‘Kooks’ to The Carpenters, considering an album with Count Dracula himself, Christopher Lee.

At the end of January Bowie embarked on his first US visit, promoting The Man Who Sold The World, already on shelves before it’s UK April 1971 release. Detained in his blue fake fur coat, (purchased at Paul Reeves’ Fulham Road boutique Universal Witness), after 45 minutes he was let through to meet Mercury promotions man Ron Oberman. “So free, so intoxicating and so dangerous’ was how Bowie described his initial reaction to America. In New York he puffed on Nat Sherman’s tobacco, met writer Ed Kellner who played him The Velvets’ newest, prettiest, poppiest album yet, Loaded. He saw them at the Electric Circus, mistaking Doug Yule for the departed Lou Reed, caught Tim Hardin at the soon-to-close Gaslight. On 54th St he bought blind Viking poet-musician Moondog coffee and sandwiches.

In California, Rolling Stone’s John Mendelsohn interviewed Bowie, accompanying him to radio shows (Mendelsohn was also in Anglo-centric outfit Christopher Milk). Mercury’s west coast promotions man and DJ Rodney Bingenheimer ferried him about in a Cadillac convertible, observing how starstruck people were by this troubadour in ‘a man’s dress’, attire that saw him barred from an LA restaurant, and staring down a barrel of a gun in Texas. So free, so intoxicating, so dangerous.

The Cadillac belonged to RCA house producer Tom Ayres who introduced Bowie to Gene Vincent (he offered the rock & roll legend ‘Hang Onto Yourself’; he died before he could cut it). Dissatisfied with Phillips-Mercury (ally General Manager Olav Wyper was gone, Oberman was going), Ayres suggested signing to RCA Victor because “all they’ve got is Elvis and Elvis can’t last forever” (Bowie also met Kim Fowley and Warhol superstar Ultra Violet).

He returned to England with bones for Ziggy Stardust’s skeleton, vinyl bulletins from weird America – the Legendary Stardust Cowboy, new favourite The Stooges. Like Performance, the encounter with Yule was an eye-opener about the malleability of identity. If he thought the frontman was someone else then surely he could fashion a new star-shaped space face-front for himself too? But if America made Beckenham seem ‘little’, ‘timid’ and ‘English’, homegrown thrills were still only a taxi ride away at Kensington High Street’s Yours Or Mine, always referred to as the Sombrero due to the large neon sign above it belonging to the restaurant of the same name.

If Haddon Hall was, in Angie’s words, ’a salon of distinction, a setting for a star’, then this was Bowie’s ‘laboratory’ where he took notes, road-tested looks; a small basement gay club grandly entered via a sweeping staircase, greeted by manager Amadeo, cigarette-holder in hand (like Bowie’s during the Hunky Dory photo sessions). The glamour factor was high – gay men congregated with impeccably styled women on the under-lit pie-segment Perspex dancefloor as the DJ spun pre-disco grooves; Miriam Makeba’s ‘Pata Pata’, Melanie’s ‘Lay Down’. By 1971 you might hear Sly & The Family Stone’s ‘Family Affair’ or Diana Ross’ deliciously hard-edged ‘Surrender’. “We were piss-elegant,” says regular Wendy Kirby who, with flatmate Freddie Burretti, was lured into the Bowies’ orbit one night by Angie while Bowie supped champagne in the red velvet booth. Other members of the Bowies’ Sombrero clan were Daniella Palmer and the hustler Mickey ‘Sparky’ King. It was this mileu that fed into ‘Queen Bitch’, written as Bowie put in a “Velvet Underground framework” but “also about London sometimes.” (see also All The Young Dudes).

Bowie was mesmerized by tailor/designer Burretti, (Kirby was convinced he had a crush on him), certain he was the “next Jagger,” predicting he’d be the first male Vogue cover star (Pin-ups Bowie nearly was). “The Stones are finished,” declared Bowie, somewhat ludicrously, given that the Warhol-designed Sticky Fingers was just out. The future apparently was Arnold Corns, conceived by Bowie, ‘fronted’ by Burretti. In May the pair graced British sex magazine Curious’ cover; puppet and puppeteer amid ‘flying dildo’ headlines But Burretti could barely sing. Bowie mostly handled vocals on May’s ‘Hang Onto Yourself’/’Moonage Daydream’.

Photo by Brian Ward

It’s hard not to see Arnold Corns as anything other than an experiment in hype, an exercise in a Warhol-style ‘outrageous lie’. Both sides of the 45 are undercooked; dress rehearsal Ziggy. But Bowie thought Mickey King ‘had something’ too – King recorded the fabulous ‘Rupert The Riley’, an ode to one of Bowie’s three Rileys, a Beatles-Stones sax-fuelled bopper, sadly missing from Divine Symmetry (a Riley’s starting handle nearly impaled Bowie that year, landing him in Lewisham Hospital).

Bowie would become a conduit for gay-bisexual energy throughout the 1970s, identifying with the loneliness in John Rechy’s City Of Night, seduced by the commitment to style. This circumvented capital-P politics – a benefit gig for the recently formed Gay Liberation Front was cancelled in October at the eleventh hour. But it was an act of bravery, inspiring artists as disparate as Jobriath, Tom Robinson and John Howard (and virtually every 1980s pop star). In 1971 gay protests railed against police brutality on Highbury Fields, while the Festival Of Light mounted its ‘moral’ crusade. Beyond this push and pull something queer was afoot; Ray Davies was seduced by a woman that was a man on The Kinks’1970 ‘Lola’, the parents in 1971 film Girl Stroke Boy couldn’t tell if their son’s partner was male or female.

Post-Stonewall and a decade after Victim’s compassionate plea for the blackmailed, closeted, decent Dirk Bogarde, gay cinema was becoming at turns stylish, unapologetic, happy to parade diabolically alluring, amoral or flawed characters. 1970 came with Entertaining Mr Sloane, Boys In The Band, and The Secret Of Dorian Gray (transporting Wilde’s novel to Bowie’s London). In 1971 there was Goodbye Gemini, Death In Venice, Villain and in July Sunday Bloody Sunday. Bowie auditioned for the Murray Head role in the film’s bisexual love triangle, a film where Peter Finch frankly faces the audience at the end and tells them he still misses his male lover. While Ziggy was incubating, his songs registered and demoed (Bowie mentioned the concept in LA), this was the world Hunky Dory took shape in.

After Tony Defries’ failed attempt to woo Stevie Wonder away from Motown/Berry Gordy, he fixed his sights more sharply on Bowie, firming up their management deal, extricating him from Mercury. In label limbo, Hunky Dory was bankrolled by Laurence Myers’ production company Gem.

After the Man Who Sold The World’s often Ronson-focused positive reviews and seeing Ronno play at London’s Lower Temple, Bowie contacted the guitarist, then living at home in Hull. Soon he was back at Haddon hall, bringing with him Woodmansey and Trevor Bolder – bassist, trumpeter on ‘Kooks’, hairdresser and the best sideburns in rock. The Spiders From Mars effectively made their debut for John Peel on 3 June at the Paris theatre, Lower Regent St., billed as Bowie And Friends, joined by Dana Gillespie and George Underwood.

Later that month, Bowie played Glastonbury Fayre, his magician’s cloak and ‘bippity boppity’ hat, another Universal Witness purchase, embellishing a 1971 staple, white shirt and huge high-waisted 20’s Oxford Bags. Taking to the stage at 5am on Sunday, the sun rose above the hill during ‘Memory Of A Free ‘Festival and shone off the Pyramid. “A turning point,” said Gillespie. “Wonderful,” said Julie Christie

Throughout 1971 Bowie and Ronson’s creative bond tightened – performing together acoustically at Belsize Park’s The Country Club and The Marquee (Bowie talked him into a dress for a pub gig), making Hunky Dory, for Ronson, ‘as a duo’. Ronson added a ferocious rock snarl to Bowie, heard on ‘Queen Bitch’, but he also enhanced Bowie’s innate elegance. Trained on violin, recorder and piano he’s responsible for Hunky Dory’s grandest flourishes, conducting the BBC orchestra on ‘Life On Mars?’, and adding a symphonic sweep to ‘Quicksand’; a daunting challenge he rose to, despite being ‘a bag of nerves,’ according to Bolder. With Visconti gone, Ken Scott produced. Formerly an engineer on previous Bowie albums, trained at Abbey Road during The Beatles era, Scott was the “suit and tie” professional Bowie called “my George Martin.”

Recording took place at Trident, deep in Soho, off Wardour Street, in St. Anne’s Court. Bowie was optimistic and impatient, delivering master takes with every vocal (‘beyond compare’ said Scott, whose recent work on George Harrison’s All Things Must Pass informed ‘Quicksand’’s layered acoustic guitars). Though Dudley Moore had been contacted, it was Rick Wakeman’s virtuoso playing, on the same Bechstein piano as McCartney on ‘Hey Jude’, that complimented Bowie’s charming ivory–hammering elsewhere. Wakeman had a busy year releasing his own Piano Vibrations, The Strawbs’ wonderful Visconti-produced From Witchwood, joining Yes (and not the Spiders) for Fragile.

1971 was the year of the singer-songwriter; Blue, Tapestry, Teaser And The Firecat, Nilsson Schmilsson, Judee Sill, American Pie, Gene Clark’s White Light, Gilbert O’Sullivan’s Himself and No Secrets. Hunky Dory could be added to the list but it’s more theatrical, quirkier drawing inspiration, and covering ‘Fill Your Heart’, from Biff Rose’s 1968 album The Thorn In Mrs Rose’s Side (Bowie would champion “the flower power Randy Newman” throughout the year, playing ‘Buzz The Fuzz’ live). Referred to as “a toy box of acoustic oddities” upon release Hunky Dory isn’t far removed from masterpieces of British arcana circa 70-72; Bill Fay ‘the voice of Mr Benn, Ray Brooks’ Lend Me Some Of Your Time, ex-Zombie Colin Blunstone’s One Year and Mandy More’s But That Is Me. Also from 1971, Peter Hamill’s Fool’s Mate is the prog Hunky Dory. A chronicler of dark mental states, the Van Der Graaf Generator frontman mirrors Bowie’s chart-unfriendly pre-Ziggy side (see ‘A House With No Door’).

But Hunky Dory had a Beatlesesque first-listen magnetism- a pop sensibility that had been retrieved and refined from the last, lost days at Deram – ‘Karma Man’, ‘Let Me Sleep Beside You’, ‘In The Heat Of The Morning’. Peter Noone declared Bowie the best since Lennon and McCartney. He took something of Lennon’s dazed, dreamy melancholy and Plastic Ono sound and some of McCartney’s White Album-era Tin Pan Alley camp (‘Oh You Pretty Things’’ piano echoes ‘Martha My Dear’’s). The shift to piano brought supple melodies and romantic moods. ‘Changes’ blended Sinatra soft-focus (major chords, strings and sax) with stuttering Beatles-pop, ‘Life On Mars?’ cheekily used the same chords as ‘My Way’ (sweet revenge for Paul Anka’s English lyric being used for Claude Francois’ ‘Comme D’habitude’ over his own 1968 ‘Even A Fool Learns To Love’). Brel’s ‘Amsterdam’ was performed throughout the year but never made the final cut.

A key influence was Neil Young’s After The Goldrush – off-kilter, piano-heavy, a dash of sci-fi on its title track’s eco-concern – spinning on the turntable on 30 May when the phone rang to tell him Duncan Zowie Bowie was born. ‘Kooks’ took the swing from Young’s ‘Till The Morning Comes’ and the sentiment from ‘I Believe In You’ (‘Changes’’ demo contains panting oddly reminiscent on Young’s 1968 ‘I’ve Been Waiting For You’, later covered by Bowie). Another major 1970 signpost was Ron Davies’ Silent Song Through The Land. Bowie’s version of spiritual ‘It Ain’t Easy’, with Wakeman’s harpsichord, would be held over for Ziggy but ‘Andy Warhol’’s arpeggio riff quoted the Silent Song’s title track. Gorgeous out-take ‘Shadow Man’ was haunted by a sadness similar to Davies’ ‘The Clown’ (with Young’s 1968 ‘The Loner’ and Bee Gees mixed–in). Another top-shelf off-cut ‘Bombers’ was in Bowie’s words “a Neil Young skit” with Deram-era eccentricities.

Hunky Dory was an Anglo-American art-pop hybrid, fusing flamenco-folk with Andy Warhol, music hall with country through Ronson’s guitar on ‘Eight Line Poem’ and ‘Song For Bob Dylan’. Divine Symmetry’s ‘King Of The City’ and ‘Looking For A Friend’ plunge even deeper into the un-Bowie swampy, soulful terrain of the era’s countrified rock. Similarly, ‘Queen Bitch’ may as the contemporary NME review noted, “camp Lou Reed out of existence,” but it’s no straightforward Velvets Xerox, coming off more nervous, like one of the tender urchins who couldn’t quite make it in The Factory’s tough scene. More English, “more Robert Smith” as Bowie noted years later. Since December 1966, when Ken Pitt gave him the Velvets’ debut on acetate, previous attempts to emulate them veered from a Mod-cool ‘Waiting For The Man’ cover to Benny Hill attempting hip US sleaze on the ‘Laughing Gnome’-meets-‘Venus In Furs’ of ‘Little Toy Soldier’ (both with The Riot Squad). Despite Stateside inspirations Hunky Dory mostly feels English due to Bowie’s vocals (excepting that Jobriath-foreshadowing gawky twang on ‘Eight Line Poem’). It could easily soundtrack the British cinema of 1971, Private Road replacing the Bee Gees on Melody.

Behind the pared-down immediacy and baroque flourishes, was a complex web of the personal and the detached. “Those songs came from within… they were a part of him,” said Dana Gillespie. You can hear David Robert Jones reflecting on his past’s “million dead end streets” in ‘Changes’ but you can also hear him ‘facing the strange’ 70’s, becoming ‘a different man’ (Ziggy?) to escape them.

He’s also there, beaming with fatherly pride on ‘Kooks’. ‘He’s going to be the next Elvis!’ said Bowie of his son when describing ‘Oh! You Pretty Things’. Here the clarion call to youth (echoing ‘Changes’’ second verse) comes with ‘a dash of sci-fi’ – references to Edward Bulwer Lytton’s 1870 The Coming Race and the Homo Superior not just of Nietzsche but kids show-to-be The Tomorrow People (not televised until 1973, Bowie apparently discussed these ideas with the show’s creator Roger Price in 1971). The media, like sci-fi was an alien force Bowie believed children would be so exposed to they’d be “lost to their parents by 12”. ‘Pretty Things’ shifts gears between sad, solo verses with the mad, apocalyptic, divine selection of a ‘crack in the sky’ and an old-time camp singalong chorus for the Artful Dodgers and Nancys down the Sombrero comes, a precursor to the Ziggy-era’s youthquake dystopia.

Even before the cutups came out Bowie’s ‘hodgepodge’ ideas were fractured and fragmentary (Burroughs thought ‘Eight Line Poem’ was reminiscent of The Waste Land). ‘Quicksand’, demoed in a San Francisco hotel was, Bowie said, a “chain reaction to the confusion about America” before adding, “it could be anywhere.” Possibly because it was really, like so much Bowie, about the search for meaning when all certainties or absolutes had vanished (it’s like 1967’s ‘Silly Boy Blue’ in a cracked mirror) . Possibly because it’s about an overly ruminative divided self, wandering through a tableaux of Himmler and Churchill, Garbo and Crowley, Homo Sapiens and Supermen. They’re signs of a soul torn not just between light and dark (Buddhism’s ‘next Bardo’ and mystical Nazism) but between egomania and crippling self-doubt (the artist-performer’s ying/yang). Throughout 1971 as Bowie built the star-shaped Ziggy his confidence occasionally faltered – crying in the bar of the Captain’s Cabin Pub, after the John Peel show, telling people ‘he was never going to make it’, telling Sounds he was a failure at 24, “a disillusioned old rocker.”

Hunky Dory catches Bowie’s sensibility in a state of flux, moving away from an introspective abyss (“I used to write drooling epics about myself”) towards ‘performance’ – life as theatre, as film, a grand façade. Andy Warhol’s created persona is indistinguishable from the Silver Screen, on ‘Song For Bob Dylan’, Zimmerman needs to speak to the titular hero. Both are constructions – Ziggy flickering through the homage.

The album’s tales of movies and generational conflict reach a dizzying peak with ‘Life On Mars?’ One of the last songs recorded, another inspirational flash that came easily, nagging at him as he strolled through Beckenham Park, forcing him off a bus, en route to buy shirts and shoes, back to Haddon Hall’s piano. It’s a grandiose show-stopper bejewelled with star turns – swirling, scything strings, Wakeman’s soloistic piano, Ronson’s flamboyant guitar. Recorders and tympani-style rolls add to the widescreen splendour. The melody’s one of Bowie’s finest (as is his searing vocal performance), majestically, sadly swooping ‘Somewhere Over The Rainbow’ (itself later lifted for ‘Starman’). But a false ending transports you back from big screen neverland to Trident – studio verité that can now be heard in its full bathetic glory on Divine Symmetry – Ronson cursing at that ringing telephone disrupting a masterful take.

The accident seems fitting on a song about, as Bowie said, an “anomic heroine,” both ‘disappointed with reality’ and escapist dreams – images that flicker in the movie theatre don’t enchant, they’re a recycled, ‘saddening bore’. Those brawling sailors and corrupt lawyers in the Alley Oop-quoting chorus are too close to the small-town violence and injustice in reality’s freakshow. But Mickey Mouse is a cow too – Walt Disney can’t offer transcendence to this disenchanted loner the way it does on Kate Bush’s ‘In Search Of Peter Pan’. ‘Life On Mars?’’ titular question isn’t scientific inquiry, it’s a desperate plea. It’s rooted in the English suburbia it sprang from, it yearns to get out.

A magical song about hopelessness, it surveys the wasteland of a post-Beatles early 1970’s. The heroine’s ejected from the family home, lost and friendless – not the fun-seeking missile of ‘She’s Leaving Home’. The 60’s had offered youth a pop that was a way of life but now it’s fractured, scattered like those mice-like hordes. It’s unable to keep the grim, grey early 1970’s at bay – the postal strikes, the rising unemployment, education secretary Thatcher snatching milk from kids’ mouths, bombs in Biba. Lennon’s empty sloganeering (‘71’s Power To The People, Imagine) can’t help those workers. Hot pants, 71’s style fad, cant’ cover the cracks. It was Bowie who’d offer a ‘alternative world’ to the 70’s lost kids’ who could spit in fools’ eyes – the kind that created punk.

McCartney, whose ‘Eleanor Rigby’ was another anomic heroine, had another that year too on debut 45 ‘Another Day’. There’d be string-accompanied others- 72’s ‘Alone In My Yellow’, from Mandy More, ELO’s ‘Oh No Not Susan’ in 1973. In 1975 John Howard’s ‘Goodbye Suzie’, the decade’s great ‘lost’ single was a morbid masterpiece about a teen not lost at the movies but under the water.

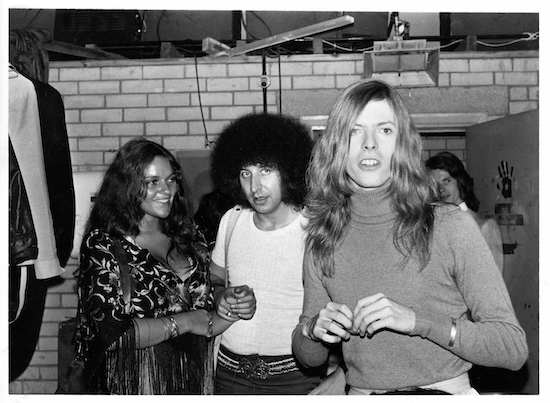

Dana Gillespie, Tony Defries and David Bowie in 1971, photo via Wikimedia Commons

Hunky Dory’s closer ‘The Bewlay Brothers’ remains shrouded in mystery, the source of much head-scratching through the years. Scott took Bowie’s dismissal at face value – gobbledygook for over-analytical US critics. Bowie’s other description, “one in a series of David Bowie confessionals, Star Trek in a leather jacket,” shows how it reveals and conceals-Bewlay, the MacGuffin of a smoking pipe, being phonetically close to Bowie. It’s riddled with false trails, but feels deeply significant, sufficiently enough to be Bowie’s publishing name, the song Lou Reed threw at Lester Bangs to silence his Bowie-bashing. It’s more likely the song contained loss, absence and sadness so profound it all had to be hidden in wordplay. Written in the studio after an unsettled, unsteady day, Bowie admitted, years later, “layers of ghosts” haunted the song.

One of them is Terry Burns, his schizophrenic half-brother, his hero who gave him Bebop and the beats; the black sheep of the family. Once Bowie became a shrewd operator, his attraction to marginal outsiders was viewed by his detractors as a vampire’s bloodlust for his next victim. but it was a pre-fame, instinctive identification, possibly shaped by Terry. Inspiration possibly comes from 60’s epics, the Dylan of cryptic sorrows, Van Morrison’s ‘Madame George’ (which Bowie covered). But the folk comes wrapped in striking sound design; a treated piano wafting through like the smoky trail of Bowie’s audible cigarette-puffing, Ronson’s backwards guitar. It’s sad but unsettling, ending in a jarring horde of varispeed voices – sonic shorthand for madness, not just on ‘All The Madmen’, but since Napoleon XIV. – Burns ‘slipping away’ from sanity, from Bowie, from Cane Hill one cold January morning years later to end his life. Throughout Bowie’s vocals subtly shift between echo-laden ‘phantom’ double-tracking and a starkly dry lone voice.

Another ghost could be David Robert Jones himself, an apt end for an album full of ch-ch-changes, of having to be released by death (‘Quicksand’), of having to become a different man for his next star-shaped move. The effect is pitched somewhere between 1971’s number one, Vincent and After All– a mind-warping wonder-house of melancholy and menace.

Not all the ghosts are Bowie’s – some could be yours. Defries certainly thought some were his, convinced it was about him and Bowie. It’s easily interpreted as a gay song too – that “crutch hungry dark,” a place where hustlers and secret loves furtively skulk in shadows, that “solid book we wrote cannot be found today” echoing a “love that dare not speak its name” (itself paraphrased on ‘Lady Stardust’.)

It’s a weird English buddy movie where mythical alliances are destroyed in the final reels – Easy Rider, Butch Cassdiy, Joe Buck holding Ratso’s corpse in Midnight Cowboy. Something precious was gone by the end some of 1971’s best films too – Harold And Maude, The Go-Between, The Raging Moon, Jenny Agutter wistfully flashing back to the outback’s ‘land of lost content’ in Walkabout. It ended Hunky Dory with a devastating kiss-off – like Blue’s dejected drunk dreamer in a sad café in 1971. Created that summer, ‘The Bewlay Brothers’ burns like a blood red sun sinking into the horizon.

After Hunky Dory things accelerated – the Bowies attended at Camden’s Roundhouse, moving closer to the Warhol crowd. In September, a second US visit, ensconced in the same Warwick Hotel suite the Beatles stayed in, saw Bowie sign to RCA Victor (a green label BOW promo featuring Bowie/Gillespie sides was circulating). He met Lou Reed and Iggy Pop, and visited the Factory, Warhol’s interest ignited not by Hunky Dory’s tribute as it played but Bowie’s Anello & Davide yellow Mary Janes. If eyes rolled as the flaxen-haired folkie mimed through his screen test, others, like Tony Zanetta saw someone with Marilyn’s star power emerging, someone able to feed off others the way Warhol did, someone who could ‘pick up on things people say and write a song about it’.

Bowie’s ever-growing confidence can be heard on the Sounds Of The 70’s performance with Ronson on 21 September. It’s on Divine Symmetry in glistening audio, as is the Fryars, Aylesbury show from days later, Bowie in delightfully camp mode, opening with an acoustic set, electrified for a full-band second half. Featuring Chuck Berry’s ‘Round And Round’, originally recorded for Ziggy, you can hear a glam rock superstar slowly being born.

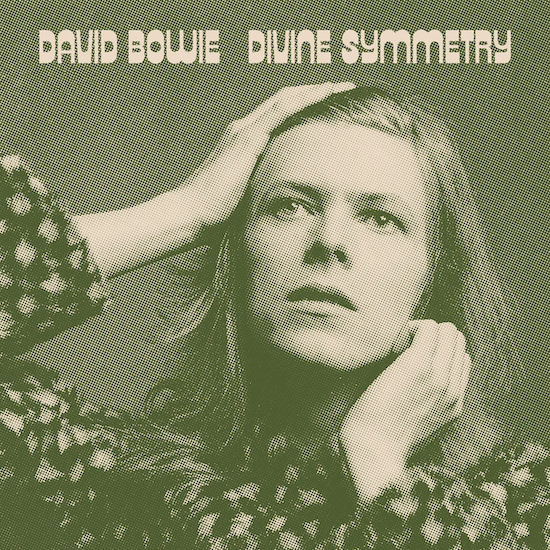

That transformation was already well underway when Hunky Dory was released on 17 December 17. Its cover caught Bowie on a cusp, sweeping back his hair, both starry-eyed dreamer and sharp-eyed student of superstardom, channelling Old Hollywood glamour – Garbo, Dietrich, Veronica Lake and Lauren Bacall. Once fame arrived, the transsexual identification flowed both ways, inspiring Annie Lennox, Julie Andrews (in Victor/Victoria) and Tilda Swinton. There’s the clown of life’s sad mysteries in those coat spots too (Bowie: “I am everyman, I am Pierrot”). Another 1971 masterpiece, Rod Stewart’s Every Picture Tells A Story, came wrapped in another vintage screen-dream sleeve.

After abandoning the original cover concept – a Crowley/Cleopatra-referencing, Twiggy-looking Bowie, Brian Ward shot Bowie at his Heddon Street studio. The portrait was retouched by Bowie’s friend George Underwood and Terry Pastor – “airbrushed for a contemporary look” – it’s colourized sepia bringing bygone Tinseltown into the deep 1970s just like that newly-minted Zipper typeface (omitted from initial US pressings). The reverse sleeve shatters the illusion – messy, hand-scrawled notes revealing Bowie’s sources- the Velvets, Frankie (Sinatra), Arthur G Wright’s original ‘Fill Your Heart’ arrangement. Like peering behind the Wizard of Oz’s curtain, a piece of post-modern myth –making/debunking echoed by ABC’s Lexicon of Love. Hunky Dory’s sound was ‘avant-antique’, a bit like the bric-a-brac from Roy Pike’s Beckenham shop that filled Haddon hall, but with a fiercely modern edge and sensibility.

Photo by Brian Ward

1971’s masterpieces came not only from those aforementioned singer-songwriters but 60s veterans (Sticky Fingers, Imagine, Ram, LA Woman), soul-funk (There’s A Riot Goin’ On, What’s Going On?, Shaft), hard rock (Led Zeppelin IV, Who’s Next?, Killer) and prog (Pawn Hearts, Meddle, Aqualung). There were other Trident Studio milestones that year – Electric Warrior, Madman Across The Water and stellar stuff from the outer-limits (Tago Mago, Church Of Anthrax). But the sense from the rave notices Hunky Dory received was that things were adrift, that Bowie was a much-needed superstar, a unitary figure for a fertile but fragmentary post-Beatle 70’s.

By the time many of those reviews came in Ziggy had formed – Bowie’s hair coiffured into that space-age mod mullet, squeezing into Burretti-designed quilted jumpsuits for his 25th birthday, January 1972, entertaining Lionel Bart and Lou Reed at Haddon Hall. Alice Cooper’s Rainbow show, November 1971 convinced Bowie’s band to mutate into glam Spiders.

If this posed a marketing problem then Hunky Dory’s initial low sales felt like destiny clearing a path for Ziggy’s grand entrance. In his wake Hunky Dory and ‘Life On Mars’ both soared to Number Three, its youth-centric songs by an expecting dad making this ‘polysexual stardust alien’ a father figure to alienated misfits everywhere – the homework-burning one on ‘Kooks’. Hunky Dory’s songs started a sexual revolution in the head, emboldening Bowie’s LGBT offspring, expanding the horizons of his straight spawn.

Hunky Dory’s mellifluous magic re-emerged in 1974 as Ziggy’s mask was cracking, on ‘Growing Up’ and ‘I’m Fine’, his contribution to Mick Ronson’s Slaughter On 10th Avenue. But Hunky Dory was terrain only sporadically revisited, as on 1999’s ‘Seven’. It’s a perverse album, transitional, forged in the shadow of another. Yet it’s one of Bowie’s’ finest, with ley lines stretching from Beckenham to The Sombrero to New York to Hollywood. A veritable manual for any aspiring composer, including The Eurythmics’ Dave Stewart, the template for Suede, ‘The Bewlay Brothers’ echoed by the shipwrecked, stricken Pantomime Horse, plucked from its lyrical maze, Anderson’s favourite word circa 92-4: gone.

Divine Symmetry’s new mixes give new twists to old favourites. ‘Changes’ comes with hitherto unused sax parts and from a different big-balled mutton-chopped swaggering 1970s (closer to early live versions). ‘Quicksand’ features a nervy, soulful early, alternative vocal, more Plastic Ono cathartic without those sweetening strings. There’s a shimmering clarity to the guitars on the new ‘Bewlay Brothers’ – though dialling down the vari-speed effects and treated piano

means the emphasis is on alternative, not improvement. ‘Song For Bob Dylan’ now sounds monitor mix fresh. The total effect is one of hearing much-loved songs from new, fresh angles, no longer in your lonely room via that dreamy cover, but placing you right there, in Trident. It’s a must-have for any Bowie fan – though whether all can afford the exorbitant £120 price tag is another matter.

David Bowie’s Divine Symmetry box set is out now via Parlophone