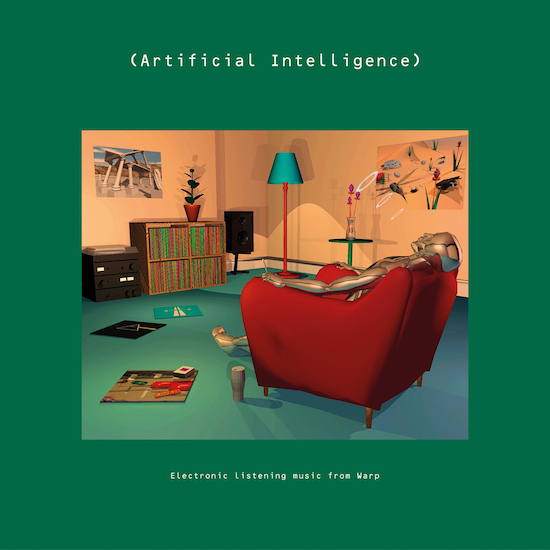

“Are you sitting comfortably?” read the sleeve notes to Warp’s 1992 release Artificial Intelligence. “Artificial Intelligence is for long journeys, quiet nights and club drowsy dawns. Listen with an open mind.”

The front cover depicts a stoned android chilling out to records by Kraftwerk and Pink Floyd with accompanying text that reads: “Electronic listening music from Warp”. It collected some of the most innovative and subversive names in British music together in one place. Many are listed under aliases, but include Aphex Twin, The Black Dog, B12, Alex Paterson of The Orb, Autechre, Speedy J, and Richie Hawtin.

Along with the release of Aphex Twin’s Selected Ambient Works 85–92 just a few months after Artificial Intelligence came out, it marked a notable shift in electronic music that removed it purely from a club context, and pumped it into people’s speakers at home, delivered in an album format specifically designed and curated to be listened to rather than danced to.

Countless new genres were being thrown at this music that eschewed a dance floor formula, ranging from ambient techno to Warp’s own suggestion of electronic listening music, but the one that stuck is the most contentious: IDM – Intelligent Dance Music.

30 years on Warp are reissuing the compilation, with its status as a document of a burgeoning and pioneering new strand of British electronic music now firmly embedded in history. Here, artists that featured on the album such as Autechre, B12 and the Orb, those involved in the album’s design Phil Wolstenholme and Ian Anderson from the Designer’s Republic, journalists Simon Reynolds and John Doran, Planet Mu founder Mike Paradinas and the co-creator of the IDM list Brian Behlendorf, all discuss the making, impact and history of the record. As well as debate the legacy of IDM both in terms of its arguably problematic meaning, as well as the culture that came with it.

Setting The Scene

Rob Brown (Autechre): The progressive house scene at the time was depressingly boring. Just loads of lame references to otherwise good work. Just stick on a four-four and get some cheesy organ on it because that’ll move bums in clubs – it wasn’t really our take on the scene at all. When people just defaulted to that it was rotting the entire scene as far as I was concerned. We were exploring all kinds of bands, like Eno, Can and Coil, that were totally off the radar of the general club scene. They weren’t anything to do with club music. It just seemed that club music was getting a bit burned out and at a bit of a dead end. Our style seemed to have infinite possibilities.

Simon Reynolds (Journalist and author of Energy Flash: A Journey Through Rave Music And Dance Culture): I had noticed people in interviews complaining about hardcore, how it was mindless and relentless and cheesy. Mixmaster Morris was a voluble voice railing against the wave of Belgian banging techno. I was really into hardcore but other people who’d been on the scene longer were just fed up with it. It was being equated with heavy metal, even described as fascistic in vibe. You did have a lot of tracks that had this almost lobotomized Wagner atmosphere – riffs like Carl Orff’s ‘Carmina Burana’. People who had been swept up in the really intense, often sinister original wave of acid house – by the time it became hardcore, especially the Belgian stuff, and things by Joey Beltram like ‘Mentasm’, they really couldn’t handle it anymore. They were burned out. They didn’t like the UK breakbeat stuff either – it was too fast, too “silly”.

Mike Golding (B12 – who appear on Artificial Intelligence as Musicology): We were in the middle of The Prodigy and rave, and it was huge, and some people got a bit tired of it. The biggest thing to do with electronic music was rave and hardcore, things were going in the charts. We went against that.

Warp and the creation of the Artificial Intelligence series

Rob Brown: We’d been sending Warp demos for a year or two. We sent them so many tapes, an hour and a half’s worth of material every couple of weeks, and one day Rob Mitchell just went: ‘Crystel’ is fucking brilliant’. If anything, that’s almost us at our most naked, a lot of the tracks we were sending were trying to get some purchase in an A&R guy’s head. We couldn’t believe they singled that one out amongst all the others that were clearly functional. This was the least functional. It was the most us. It’s almost like you suddenly know you can trust someone when they mention something that’s so out of the blue that it could only be legit, so we kind of went with that and sent them more of those kinds of tracks that were more us. That gave us more confidence in what we chose to do and we’ve managed to just do our own thing ever since.

Steve Rutter (B12): We met Richie Hawtin before Artificial Intelligence to talk about putting something on his Plus 8 label and we played him the tracks that went on the album, but we never heard from him again.

Mike Golding: We started our own record label because no one was really interested in us. We thought we can’t just set up a record label and be like, the artists are Mike and Steve. It doesn’t sound very professional. So, we said, why don’t we just make up a few different artists’ names? People might think it’s bigger than it is and that it’s not just a couple of blokes in East London. We were geeks. So, the fact that we hid our identity wasn’t a marketing ploy, it was a necessity.

Steve Rutter:Warp reached out to around half a dozen artists. We got this fax saying everyone’s meeting in the pub, it’s about the electronic music movement or something. It was really vague. We met in this pub and there was Aphex Twin, Black Dog, A Guy Called Gerald, it was almost like this fabled meeting. It was a room full of introverts and music bods who had no idea who each other were or why they were there.

Mike Golding: The album concept didn’t really exist for rave music at this point.

Steve Rutter: Rob Mitchell’s vision was sitting down listening to a body of work of this type of music.

Phil Wolstenholme (Artwork for Artificial Intelligence): Artificial Intelligence was a project that had been in discussion with Warp for some time, partly due to the burgeoning scene centred at the Warp shop, and also to the amount of after-party music sessions that were unfolding at various people’s homes, and the inevitable raiding of long-forgotten album collections that would result. The scene was very broad and quite eclectic, and very few musical prejudices existed, especially at 7am. Most of the dancing was done for the evening, so it was time for some variety.

Rob Brown: I think Warp wanted to tie these things together. They’d seen something happening that we’d been aware of for a long time. It was interesting to see that a label had actually decided to investigate these weird tracks that people were playing after hours and we knew we were part of that kind of catalogue as it would emerge over time.

Steve Rutter: There was this little genre which we loved, which occupied quite a small, and ever decreasing, space and Artificial Intelligence really brought it out as a big contender amongst all this other stuff that was going on. Warp wanted to present a movement. Like a community.

B12, photo courtesy of Warp

Ian Anderson (Designers Republic): It was a conscious decision to do something a bit different to what else was happening. To establish Warp as a label that wasn’t just a dance music label and that they could release albums. Warp were building a roster of artists who they wanted to develop, which was another sea change. Before it might have just been licensing a 12”. It was quite visionary. It was always conceived to be the start of a series.

Rob Brown: For us it felt like a bit of a steal. Like we were in a bit of heist, because we were nobodies at the time, all the other names were massive. We were suddenly stepping into this arena with all these established artists – like getting to become stablemates with a lot of artists that you’ve been following for years. I was a little bit bamboozled, a little bit startled, but also like, well, fucking hell, thanks, about time.

Alex Paterson (The Orb): Aphex Twin used to come down and listen to us play for six hours back in ‘89. I don’t want to say we were an influence on it but we were definitely part of that whole scene. I wanted to be part of that scene too and in many ways I wish The Orb was on Warp, rather than Mr Modo because that fell apart in 1994.

Mike Paradinas (μ-Ziq / founder of Planet Mu):

It was an exciting time, definitely. I think producers were making this kind of stuff all the time anyway, it would just go on the B sides. So, it had been coming anyway. But to put it all in context, like Warp did, was the clever move.

Release And Impact

Simon Reynolds: It did feel like a significant release – but more for the concept than the contents. There had been a little spate of moves in this direction. Earlier that year there had been a compilation on Kirk Degiorgio’s label Applied Rhythmic Technology called The Philosophy Of Sound And Machine, which similarly rounded up atmospheric electronic tracks by operatives on the edge of the dancefloor – including some of the same people on the Warp comp, like Richard D. James and The Black Dog. R&S records had started a sub-label called Apollo that had more ethereal, dreamy tunes on it. So that was a label identified with the most banging Belgian hardcore techno opening up this other front of serene soft-core. But Warp’s release got the most attention and it really emblazoned the whole slightly dubious concept of “intelligent techno” with the name Artificial Intelligence.

Rob Brown: I think it would have been even more groundbreaking if it had been all artists that no one had heard of like Autechre and loads of other people. It was predominantly older, big artists. So it was kind of cheeky that they were saying this is new stuff. It’s almost like they’ve harvested a load of heads that were already above the parapet. I think Warp had a bit of a coup with that. Maybe a lot of artists were getting sick of having to be a certain thing and this gave them an outlet and that outlet was a certain style where no one’s going to demand anything other than creativity on a boundless level where there’s no real rules. And that’s kind of what we’re all about anyway. We never gave a shit about rules.

Steve Rutter: At the time it just seemed like it wasn’t a big thing. Me and Mike were super proud of B12 records and what we were doing by ourselves, and it just seemed like Warp was another label wanting to do something. It didn’t seem that big of a deal but looking back now it’s a huge deal.

Mike Golding: You couldn’t tell the significance at the time. No way. Everyone who was making electronic music at that time was all in their own little bubble. It wasn’t this big community of all people that were there changing the world. It was small little bits.

Ian Anderson : It was a landmark for Warp’s position at the time to come out and tap into this thing where people were making electronic music to listen to at home. My perception was that this was something different. It’s something really interesting and the right way to go. It just hit at the right time when there was a general feeling that people wanted something a bit more than just 12 inches and remixes.

Simon Reynolds: There was a little buzz gathering around Aphex Twin through ‘Analogue Bubblebath’. It was really the double whammy of Artificial Intelligence and then R&S putting out the Aphex Twin album Selected Ambient Works that really put across the idea that there is this new “electronic listening music” direction brewing. Then you started to hear about people throwing ambient tea parties – Sunday afternoon chill out sessions for the rave-burned to recuperate. That was like a revival of something that had been hyped about 2 years earlier, around the first records by The Orb. Suddenly it was on again.

Artwork

Phil Wolstenholme: I’d done a couple of sleeve designs already for Warp prior to this project, and Pioneers Of The Hypnotic Groove had already been constructed entirely as a 3D scene, not easy at the time, but it generated plenty of ideas about how to keep moving forwards. The living room on the cover was basically an expansion of all our living rooms, and the cover concept came quite easily, formed between me, Rob Mitchell and Steve Beckett, but the practicality of building the scene was a little more difficult. When the final artwork was delivered, Steve told me that it was almost exactly what he had imagined, which was a relief after all the time it took to create – 12-hour renders were quite common in those days, and so the work process had to become extremely disciplined in order to progress without simply watching an hourglass pointer keep turning.

Simon Reynolds: In some ways, the cover was more talismanic than the music inside, which was a bit motley, as is so often the case with compilations. You had this witty and striking image of the robot spliffing up and chilling out, plonked in his armchair in front of a nice looking hi-fi set up. All the paraphernalia of the chill out session is there –the Silk Cut packet, the Rizlas, the can of import lager. And then the record sleeves are clues – Pink Floyd’s Dark Side Of The Moon, Kraftwerk’s Autobahn – almost saying: this is the canon that we are extending.

Ian Anderson: We included artist questionnaires on the sleeve design to make their personalities part of the whole thing. It was a way of meeting the artists and helping people join the dots and see what they are into. It was at a time when people celebrated anonymity. People didn’t really know what to expect so it was just a way to introduce the artists.

Rob Brown: The cover was a breath of fresh air. It’s a paradox, isn’t it? It’s warm and cold. Look how warm the room is in the lounge, the lamps, there’s no big light on it, he’s leaning back with a joint but he is a chrome humanoid. There’s warm and cosy and cold and stark, it depends what you want to see in it. The green I was never sure about though. I think they just wanted to make it almost look a bit too ugly to be a dance record.

Mike Paradinas: That’s what everyone did. Everyone was smoking joints and listening to pirate radio in their rooms. It’s just a natural extension of that from the dance floor as it is on the front cover, someone smoking and listening to it. Albeit a robot.

Phil Wolstenholme: Using other people’s artwork did feel like a bit of a gamble at the time, possibly the most contentious part of the concept, not least as they weren’t just any old people. But they were also used as they were very powerful graphical symbols, not just for the specific music they represented, but culturally too, in creating the wider scene of musical expansion that Warp were working within. They were also specifically used because their graphic simplicity meant they’d always be recognised, at any size – again, a gamble, but I was hoping that they’d see it for the tribute it was, rather than being exploitative. And they’ve not complained – so far.

I’d also always been impressed by the work of sleeve-artists Hipgnosis, and their use of the ‘cover within a cover’ [Droste effect] concept was a favourite of mine, and the use of the Pioneers Of The Hypnotic Groove sleeve in the foreground of the AI room was a definite homage to their work. Incidentally, the Evolution Of The Groove image was shown as a poster on the robot’s wall, which had just been released, so we had a nice virtual timeline running through all the sleeves.

The birth of ‘IDM’

Alex Paterson: There’s lots of different terms I don’t like and that’s one of them that I don’t mind at all. If someone called me gabba then I’d be upset.

Mike Paradinas: It was the start of the transition to listening music and albums but we still called it techno or if you went to a record shop you’d say: ‘have you got anything like Aphex Twin?’ There were no divisions at that time. It wasn’t until I started touring in the states in ‘95 that I heard the term IDM. People were asking me about IDM in interviews and stuff, I had no idea what they were talking about.

Brian Behlendorf (co-founder of the IDM list):

I had set up a mailing list called SF raves, so that everybody who knew about the rave scene in San Francisco and that had email, which was kind of rare, could share where the parties were. There were 300-500 people and that kind of took off. Around the same time was these other regions of electronic music coming up. So I thought, why don’t we create a mailing list about these two kinds of emergent music trends that seem to not really have a similar home. One of those was the whole Warp records, intelligent dance music kind of angle, the other was more ambient music.

It was a community. The idea was that these are spaces for discovering new music and sharing ideas. It’s hard to describe to people who have entirely grown up with current social media, but there was a time when you used to love the idea of having a conversation with somebody you’d never met on the other side of the world. It was a time when that felt like the future – a merging of the global brain. At the time, this sense of content and community were inextricably linked. We weren’t trying to replicate a music magazine online; it was much more like a conversation in a pub. I won’t take credit for coming up with three letters together, IDM, I’d credit [co-founder] Alan Parry.

Simon Reynolds: I was interested in the music but could see that there was something problematic about the term. I was totally up for home-listening, album-length electronic music, but the idea that this was inherently more advanced than the dancefloor oriented stuff. Well, firstly this was clearly not the case if you were listening closely to what was happening with the darker breakbeat hardcore music being made by 4 Hero, Foul Play, Omni Trio, Goldie and many others – it was incredibly sophisticated music, just maniacally fast. There was no lack of complexity there.

I think the term Warp originally bandied around – “electronic listening music” – would have been a fine term and I wish it had stuck. It’s neutral. It describes a function and context – home listening, headphones, chilling out with your mates. There’s no judgement or snobbery embedded in that. But when people started going on about Intelligent Dance Music, it seemed to be based on some unexamined assumptions about the superiority of a cerebral response to music versus a physical one. And a whole bunch of class-based snobberies were compacted in there.

Mike Paradinas: None of us thought we were taking the piss out of music or doing a white middle class version of it. Given the fact nowadays most of us would identify as autistic could be one reason why this sort of music exists. It is quite self-absorbed, for loners and introverted people. I think that’s the reason for it existing rather than any sort of class thing.

John Doran (Editor and co-founder the Quietus): Is the genre name IDM problematic? First of all, I want to say for the record that nearly all genre names are terrible. So, on that level I already find the idea of Intelligent Dance Music, slightly embarrassing, but I don’t think it’s that much worse than hip hop, death metal, punk, shoegaze, the scene that celebrates itself, or whatever in terms of being vaguely cringeful if you actually stop and think about the language being used.

But does the fact that IDM has never gone through a lexicographical unshackling – it’s never really lost the sense of ‘this music is for smart people, that other music is for dummies’ – mean there’s something worse than mere naffness going on here? Drew Daniel of Matmos, someone whose opinion on music I respect, said: “If you consider the sociological origins of contemporary electronic dance music in black and gay clubs in Chicago and New York and then consider the overall ‘whiteness’ and ‘straightness’ of the average IDM artist and fan it all starts to look kind of sinister.” Does that view hold as much water now if you look at artists such as J-Lin, Thundercat, Loraine James, Flying Lotus, Yves Tumor and so on as being the most important ‘IDM’ artists of the last decade? The optics of IDM as a name aren’t great; I would have called it something else.

Rob Brown: Rob Mitchell was like we’re going to do this thing. It was kind of casual. Warp are very cheeky, they’re kind of a funny lot. And they know when they’re winking at you but I think other people see it as a very lofty establishment looking down on the mere mortals with their big new ideas and I guess we get that levelled at us sometimes. ‘Artificial intelligence’ was just kind of a hip buzz word.

Ian Anderson: At the time artificial intelligence was something that people talked about but didn’t really have access to, it seemed to be something which caught the zeitgeist and explained, in some way, what their ambition for the music was. I do remember there were quite a few people that heard it and got the impression that it was people trying to make dance music who’d missed the point.

Rob Brown: My take was that intelligence meant just being free thinking and open minded, and artificial was, yeah, it’s techno music. It’s electronic sounds. And I’d go with that. I think the idea of intelligence was maybe just unfortunate. They just thought it’d be a catchy buzzword that wouldn’t get misunderstood culturally – like oh, it’s not dance music and stupid people dance, so this is for clever people. A lot of flag waving could come out from that but dance music has always been like that. Is it fluffy bra piano house or is it New York garage? People always have these quantifiable critiques where you have to look at what the latest thing not to be into at the time is. I think that was going on all over the place and this was just another example of that. But in America, a lot of people became really tribal about it.

Brian Behlendorf: The oldest email I have from the IDM list from a member has the subject “can dumb people enjoy IDM too?” This was my response:

‘The term "intelligent" was used primarily because of Warp’s Artificial Intelligence series – it just seemed like a good way to describe a sound while leaving plenty of room open for interpretation and invention. The focus should be on music that is more than just bounce-up-and-down music… but even that to a point is a matter of perception. Like all mailing lists, the topic of conversation is entirely up to the members. If you wanna talk about gabba, go ahead ;)’

Often you name things early on that take on a life of their own. In retrospect, you might have had second thoughts but sometimes you need a provocative name that causes people to go, ‘what the fuck is that?’ and to get across that it’s different and worth a second look. And so you could almost think of it as like a self-parodying term that intended to be provocative.

John Doran: The UK generated a whole bunch of potential names – all of them a bit shit, but none of them outright offensive. Ambient Techno. Art Techno. Electronica. Not great, but not red flag bad. The Warp compilation itself calls the music Electronic Listening Music which I could have lived with. What makes me laugh is that not only did the people behind the message board ignore this genre name being handed to them on a plate but they made what I consider to be an ironically dumb mistake in assuming that the most important bit of the compilation title was “Intelligence” when in fact is was “Art”. But – and I think this needs to be said loud and clear – no one is ever thinking about posterity when they coin these names; if they were, they’d be better. The best of the bunch was actually Braindance, the term coined by Grant Wilson-Claridge, who set up Rephlex with Richard D James in Cornwall in 1991. As spurious sub-genre titles go, it’s definitely goofy but it’s a lot more wide-eyed and full of optimism, but it was pretty much ignored by everyone. I still sort of think it should be implemented.

Aphex Twin

Simon Reynolds: The IDM list was a genuine community and it had international reach. You had a lot of brainy, nerdy people arguing interestingly. But like any community, it has its groupthink, its biases, its blind spots and deaf spots. The IDM lot – artists and fans – did cotton on quite quickly that something revolutionary was happening in jungle and drum & bass, but because their experience of it tended to be more domestic and private, they didn’t really grasp the collective vibe power of it as a dancefloor thing. A lot of IDM people were in America, a very long way from the London action, and they picked up on all the very fiddly, intricate beat-editing but not the spiritual-visceral power of the bass. And the way the samples in jungle – from reggae, soul, jazz-fusion etc – have this community memory aspect. They weren’t listening to the music to dance to, or to have a collective experience with it.

It was divisive – there was a kind of parting of the ways. As someone who uses language in my job and also had read a bit of critical theory, I could see all the biases that were entwined with this rhetoric. Not that you had to dig deep really – it was right there on the surface. In Energy Flash I have an analysis of this phrase you would get on certain flyers – “no breakbeats, no lycra”. It was a promise that the club would be playing so-called intelligent or “serious” techno, none of this breakbeat hardcore nonsense. But it’s also about the kind of people you’ll be rubbing shoulders with in the club – no sweaty, pilled-up ravers here. It has a tone of snobbery reminiscent of things people say about chavs.

John Doran: The idea that this is a split between middle class university sorts making poncey music you can’t dance to versus working class ‘ardkore guys churning out functional but revolutionary bangers is a false binary and feels like a construct designed to cater to pre-existing biases. With tunes like ‘Human Rotation’ and ‘Digeridoo’ Aphex Twin had already cemented his position in the history of hardcore and just weeks before the release of Artifical Intelligence, under the name of Powerpill he had released a “novelty techno” track called ‘Pac-Man’, Autechre’s roots are in electro and so on. I think most of the major original players in this nascent scene weren’t anti-dance by any stretch of the imagination, they just saw the idea of home listening as another string to their collective bow. Ultimately, I just think that a small number of heads in Cornwall and Sheffield felt that dance music had taken something of a wrong turn a few months beforehand in cities like London and Manchester and were trying to influence UK culture according to their own vision and willpower, which is no great crime in my book.

Purely for white blokes?

Brian Behlendorf: We were ignorant because we didn’t see people’s faces and people liked to use pseudonyms. So, we didn’t really have a concept of that. I hate saying that because often that is a release valve for responsibility and 30 years later, I probably would do a lot more intentionally to figure out how to bring in different voices, but anybody could have shown up, from any race or gender, and participated. The door was wide open. I’d really like to believe this is true, and I think it is true, that we were colourblind in our engagement.

Rob Brown: We toured America shortly after the release of Artificial Intelligence and you’d have dudes coming up going, ‘oh shit, you’re white! This is techno, why are you all white?’ We’re like, well, in England, lots of people like techno. We were also freaked out because the audience wasn’t as mixed as we thought it would have been. I think the majority were more mature listeners that were checking it out because it was slightly different and it was this unique opportunity to check out this weird stuff from the UK. It was a bit of a downer that it wasn’t as multicultural. We wanted the audiences to reflect the influences that we’d had from all over the world and suddenly we seemed to be, as far as the Americans were concerned, the influence.

So it kind of seeped into a mentality that this was special or for more interesting types. I agree with that to an extent in terms of the sound, but I didn’t agree with it in terms of it becoming a culture that was isolating its past a little bit or denying what its influences were. So it was good that we got that out there on the sleeve [via the questionnaire]. We’ve got a lot of influences and references and we thought we need to represent the strata that has brought us into being. I think we could already tell straight away it was being misunderstood, or at least it was bifurcated in ways that we couldn’t predict.

Mike Golding: I think it was pretty blokey. It’s just inherently a blokey thing. If you look at MS DOS, it is just the least inviting thing in the world. There was never an idea around exclusion. It was just the way it was.

Steve Rutter: Back then, I wouldn’t have even considered race, colour, creed, sex. It wouldn’t even come into my mind. We were just doing music. Maybe I’m being a bit naive and I don’t know if that sounds shit but it was just about music.

B12, courtesy of Warp

Mira Calix (as told to Vice in 2018): I was the only female artist on Warp. We can and should be critical of it, but at the same time if the record labels weren’t releasing lots of music by women the kids weren’t gonna write lots about music by women. My label wasn’t a hostile environment at all, it was just a lack of women putting themselves forward and a lack of opportunity. It’s not like it was a macho culture. As I’m aware, the list wasn’t particularly macho; I think it was a bit more geeky. That is a more masculine trait: I hate to say it. That doesn’t mean women don’t collect records — obviously, you’re speaking to a girl who is a geek or I wouldn’t be doing this [laughing], but I think it’s fair to say that trainspotters are mostly men, and birdwatchers… There were less women releasing and performing – like very small amounts – and there still are. Forget about the genre: that’s anything from bloody drum and bass to a symphony. We see very visible women like Beyoncé and Rihanna so we think things are more balanced, but actually women are still a minority in the industry, 20 years later.

I don’t think anyone at Warp was just sitting there looking at the List; it wasn’t used as some sort of bellwether. What was appreciated was the support, because it created a culture, a scene, a new form of communication: people being online, that was the first social media. I think that wouldn’t have necessarily happened around a rock band. Because the music was hyper-experimental and had a connection with technology it attracted those kinds of people as well. I remember some artists at Warp kicking back, going “IDM? It sounds poncey”, but upon reflection, it’s just a name. Like calling stuff garage or house.

Reflections:

Mike Golding:It’s amazing that people are still talking about it now. When you listen to this today, amazingly, or kind of maybe depressingly, this could have been released yesterday.

Ian Anderson: In hindsight, it’s a landmark album. It really broadened the horizons of the label.

Rob Brown: No one ever really knows when history is getting made and anyone that hails something is going to be changing the universe usually seems a bit mad. It was just nice that people were realising that you could actually have electronic music that wasn’t just focused on selling units out of the back of the van on white labels or taking over a club. I think people realised they don’t have to be like a sheep with this herd mentality or joining the nearest biggest queue.

Warp’s 30th anniversary edition of Artificial Intelligence is released on 9 December