Photo credit Wikimedia Commons

Loneliness – woh woh – seems to be my destiny

Made to cry in the night

No one seems to treat me right

Loneliness – woh, woh – what’s to become of me?

Joe Meek, lyrics for ‘Loneliness’, sung by Mike Berry.

It’s too soon to know how the destruction – sorry, regeneration – of London’s Denmark Street will benefit the musicians whose legacy it has been sold and marketed upon. One silver lining, or more accurately a brown one, is that the demolition work has helped to dislodge the 1,864 reel-to-reel tapes, originally packed into 67 tea chests, left behind when maverick producer Joe Meek fatally shot his landlady Violet Shenton, and then himself, on 3 February 1967 – eight years to the day of the death of his idol Buddy Holly.

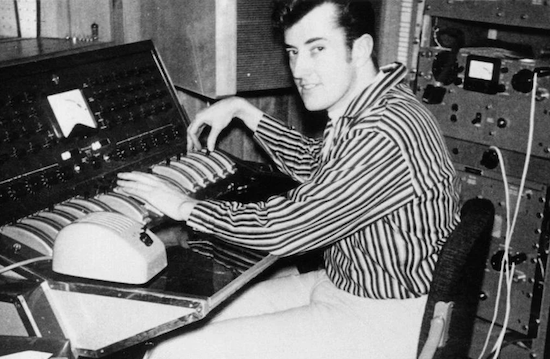

Meek is, deservedly, a legend – a social, cultural, and sexual outsider who took on the music machine and, at least for a short time, appeared to be winning. Hailing from a modest rural background, driven by an unshakable need to create music while having little training, or formal musical ability of his own, he moved to London, set up his own independent labels, Triumph and RGM (for Robert George Meek), designed and built his own innovative audio equipment, developed production techniques that would become industry standards, wrote, recorded and produced music from his own home studio, and created visionary music alongside chart topping hits… all bootstrapped together on a fraying shoestring budget.

While they may appear jaunty and upbeat on first hearing, Meek’s recordings are suffused with a deep melancholy that would have been largely unknowable to most of the teenyboppers who heard them, but spoke of his own sorrow and alienation and, that of generations still haunted by war. Meek’s use of sound effects and swathes of ghostly reverb, woven into seemingly innocuous pop songs and rock and roll instrumentals – as if the BBC Radiophonic Workshop was directed by Phil Spector – created a sense of the sublime and hinted at strange realities beyond our own.

It’s a testament to his unique talents, and his faith in the transcendent power of music over life, and death, that his songs are still enjoyed, even if their enduring pleasures are overshadowed by the pain and tragedy of his private life.

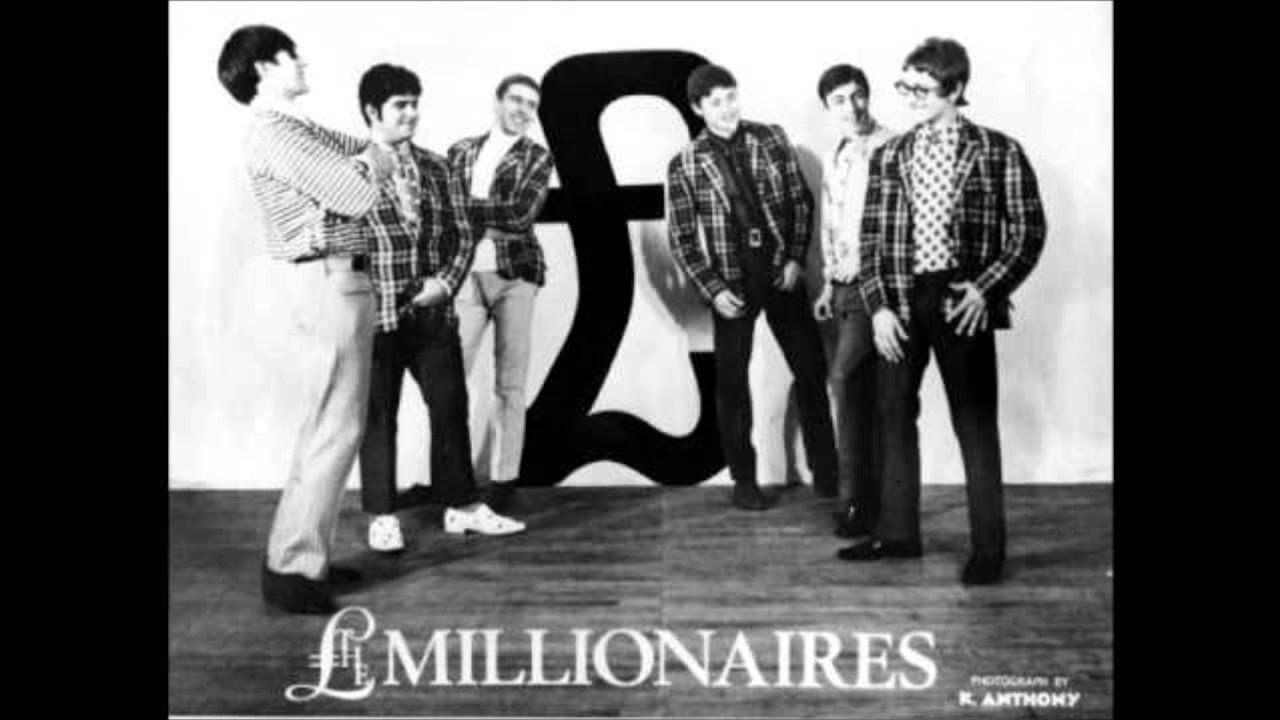

The Millionaires – ‘Wishing Well’

(1966)

The Tea Chest tapes, as they became known, were bought from Meek’s executors by Orange Amps founder Cliff Cooper, bass player for The Millionaires, who recorded the whimsical single ‘Wishing Well’ – a solid, representative RGM production, if not a standout – for Meek a year before his death. By 1967 Cooper was building a recording studio in the basement of his home on New Compton Street – a setup not unlike Meek’s own.

Sold for between £300 and 400 (about £7000 today) on the express grounds that they were to be used for recording over, and not for the music that they held, Cooper thought that buying a job lot of tapes would save him a small fortune in the studio. He might also learn a few production tricks by listening back to them. And that was pretty much the last anyone heard of them, until now.

Over the years, members of the small but vociferous Joe Meek Appreciation Society had characterised Cooper as an industry villain for refusing to share the wealth contained on the tapes – despite his insistence that he wasn’t legally able to. This culminated, in February 1999, in "the siege of Denmark Street", when about 70 members protested outside Cooper’s property where the tapes were stored, insisting that he hand them over to the National Sound Archive for preservation.

Two decades on, Cooper has finally sold the tapes, which he had gone to some lengths to catalogue and preserve, to the archival label Cherry Red, whose series of reissues debuts this month, the 60th anniversary of ‘Telstar”s release, with two EPs: one dedicated to ‘Telstar’ outtakes and demos, the other from Meek protégé Heinz. Both EPs provide fresh insights into the madness of Meek’s method.

And there is much more to come. Somewhere within the vast magnetic tangle are early demos and recordings from The Konrads (featuring David Bowie on sax), The Raiders featuring Rod Stewart, Status Quo, Tom Jones, and Mark Feld (soon to be Marc Bolan).

And, through the choir of voices, calling out to us across time, radiating through the vast washes of reverb and tape echo, is the spirit of Joe Meek himself – still lonely, still yearning for love – a lost, complex soul who remains much harder to unravel…

Jenny Moss – ‘Hobbies’

(1963)

Like many artists and inventors Joe Meek was both a man ahead of his time, and an antenna so finely tuned to the zeitgeist that it ultimately overwhelmed him.

Born in the Forest of Dean in 1929, Robert George Meek’s family was haunted by loss: his older brother, Arthur, was named after an uncle who never returned from the First World War, while his nickname, Joe, given to him by his grandmother, was the name of her other lost son. His father, George, suffered lifelong shellshock (PTSD), which would send him into uncontrollable panics and rages, something the adult Joe would also experience, though often for chemical, lozenge-shaped reasons.

Perhaps in an unconscious attempt at protecting him from the male trauma that was such a signature of their age, his mother, Biddy, dressed Joe, her second child, as a girl, and treated him as one, until he went to school.

Young Joe did boy things – he gazed at the night skies, performed magic tricks and tinkered with electronics – but he took them further than most, including building what may have been the first television in Gloucestershire (though there was nothing to watch on it). Aged eleven, with war once again consuming his world, and seeking a new trick for one of his magic shows, Joe gathered up some white phosphorous left behind after a local military demonstration, resulting in injuries that very nearly cost him his hands, and required him to spend many months in bandages. It’s hard not to project deeper meaning onto this combination of gender ambiguity, physical trauma and the lingering presence of death: hallmarks, in so many cultures, of the sorcerer’s, or shaman’s path.

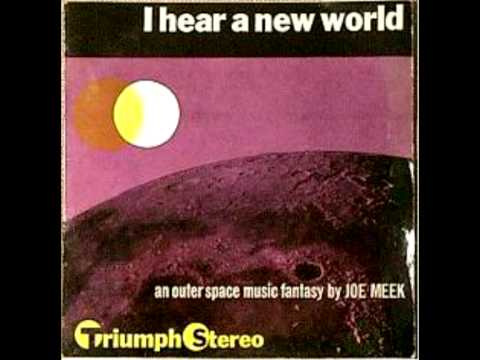

‘I Hear A New World’ from I Hear a New World by Joe Meek & The Blue Men

(1963)

On leaving school Joe did National Service with the RAF, working on radar, followed by a stint as an engineer at the Midlands Electricity Board, where he began his first experiments with tape recording, cutting his first LP, a collection of field recordings and sound effects, on his own custom-built lathe.

These experiments lead, a decade later, to the magnificent I Hear A New World, a concept album (perhaps the world’s first) about life on the Moon, initially privately pressed in only 99 copies. Its disorienting mix of austere concrète-style tape wrangling and inane chipmunk ditties has seen it both dismissed as a novelty record and hailed as a masterpiece of experimentation on a par with anything emerging from the continent’s more formal studios, utilising then-novel sound-on-sound recording techniques and tape effects.

The album’s title song is a beautifully melancholic, innovative piece of cosmo-exotica that strikes right to the heart of Meek’s personal alienation, and his yearning for something else.

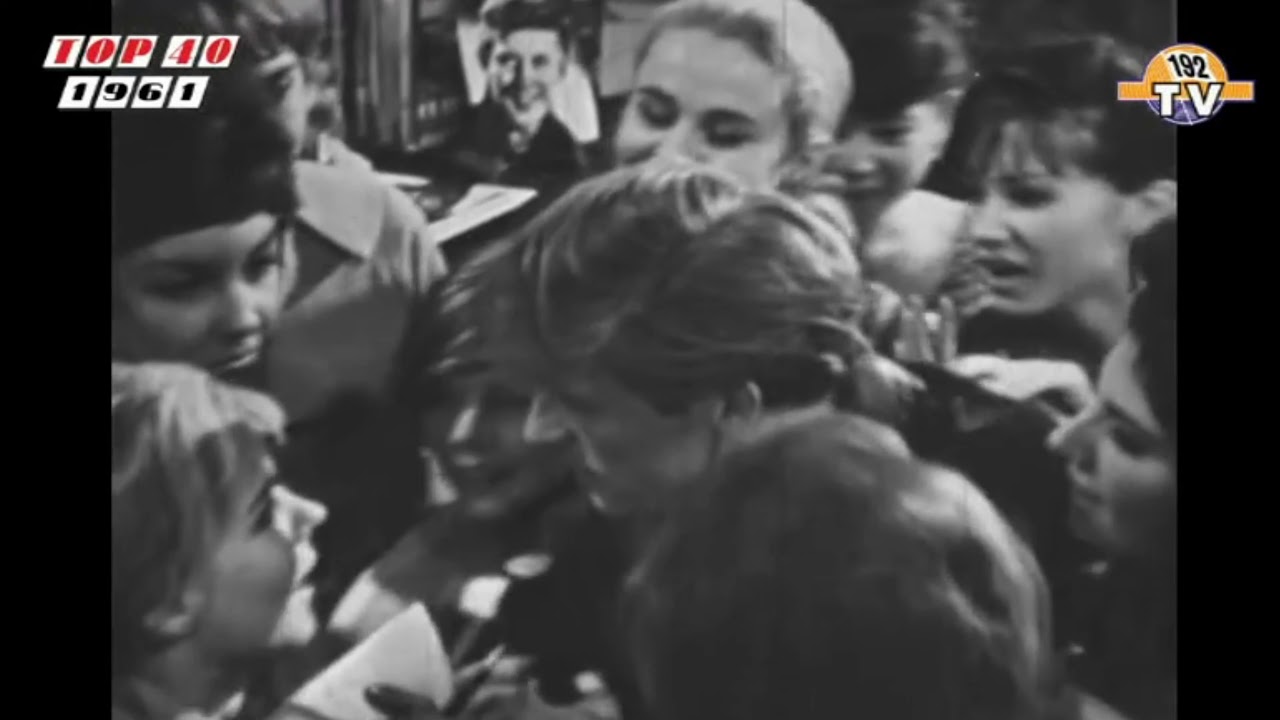

John Leyton – ‘Johnny Remember Me’

(1961)

Meek’s first number one hit was this haunting and sensational number, written by the supremely talented Geoff Goddard and sung by the young John Leyton, who was already a minor star for his role in a TV adaptation of the gung-ho Biggles books. Goddard shared Meek’s predilection for the supernatural and told Psychic News in 1961 "“I am sure I receive my inspiration from the spirit world. When I wrote ‘Johnny Remember Me’ it was early morning and I had just opened my eyes. I always keep a tape recorder by my bed, and I sang that song into it without working on it at all.”

In a moment of early marketing nous, just before the single was released, Leyton appeared as a rock star in the TV drama Harpers West One, set in a department store. His performance of the song in the shop’s music department, surrounded by adoring young fans, propelled it to the top of the charts, despite being voted a miss on BBC TV pop show Juke Box Jury.

Leyton would also record the excellent ‘Wild Wind’ (a number two) with Meek, and go on to act in The Great Escape (1963), Von Ryan’s Express (1965) and others.

Mike Berry And The Outlaws – ‘Tribute To Buddy Holly’

Banned by the BBC for its “morbid concern over the death of a teen idol”, this story-song, also written by Geoff Goddard, reflects his and Meek’s shared obsession with Buddy Holly, the American rock and roll pioneer, and martyr, who died in a plane crash on tour in 1959. Meek, like many others, felt a close connection to the singer, and claimed to have received a premonition of his death during a tarot card reading, causing him to write a flurry of letters to Holly’s and record companies, warning them of what was to come. Unfortunately the psychic flash gave Meek the correct date, 3 February, but was a year too early. (It also predicted the date of Meek’s own death, 9 years hence).

A firm believer in life after death, Meek conducted regular seances, during which

Holly made appearances as a spirit guide, along with a suicidal American Indian chieftain and the pharaoh Ramesses the Great (not to be confused with the tragic, cosmic, 1970s rock musician, who, in an alternative musical history, would surely have worked with Meek).

The Moontrekkers – ‘The Moontrekkers’

(1961)

Another record banned by the BBC, as being “unsuitable for people of a nervous disposition”, this perky horror instrumental came from a young band called The Raiders, whose 16-year-old singer, Rod Stewart, was booted out of Meek’s studio with a loud raspberry and much frantic hand waving. They became The Moontrekkers for this Rod-free track, which opens with ominous howling winds and concrète tape creakiness and ends with a terrifying scream – an impressive cameo from Meek himself – bookending a cheeky, reverb-drenched cemetery creep.

The Raiders replaced Rod Stewart with another singer, Bobby Shafto, from Hornsey, North London, who would later find minor fame. Curiously, Shafto’s real name was Robert Farrant, who was, disappointingly, no relation to another Hornsey Farrant, David, who achieved notoriety in the early 70s as the instigator of the Highgate Vampire panic, and once met Meek when they were both out seeking spirits at night in the then extremely run-down Highgate Cemetery.

Heinz – ‘Just Like Eddie’

(1963)

German-Brit Heinz Burt was working the meat counter in a Southampton grocery shop when Meek spotted him. Meek found him a role in pop idol Billy Fury’s backing band, The Tornados, with whom Meek would create his immortal instrumental hit ‘Telstar’. But Joe had other, grander ideas for Heinz, with whom he was madly in love: he moved him into his flat, dyed his hair blond (inspired by the sinister alien kids in the 1960 sci-fi film Village Of The Damned) and wrote tunes especially for his beloved new protégé. ‘Just Like Eddie’, a tribute to another dead American rock and roller, Eddie Cochran, is a classic Meek stomp, also notable for featuring Richie Blackmore, later of Deep Purple and Rainbow, on guitar. When Meek and Heinz eventually fell out, he moved out of his flat, leaving behind the shotgun with which Meek would later play out his own tragedy.

Screaming Lord Sutch & The Savages – ‘Jack The Ripper’

(1963)

One of Meek’s great contributions to British cultural history was his discovery of David Edward "Screaming Lord" Sutch, who was already making a name for himself as a wild performer on the live circuit. Joe hauled him into Holloway Road to record the roaring goth rock number ‘Til The Following Night’, with its extraordinarily long horror introduction showcasing Meek’s sound effects skills. An incredible performer and a true eccentric, Sutch’s stage presence was famously terrifying and occasionally out of control, incorporating stunts like firing a starter pistol at audience members, for which he would be arrested. Sutch always wore his hair long, which may sound trivial now, but in the 1950s was bordering on the outrageous. "Mum sometimes wondered if she had a son or a daughter", Sutch would later remark, in an ambiguous statement of outsider-ness.

Sutch lived with his mother throughout his life, killing himself in 1999, shortly after her death. This rare film shows him in 1964, performing his hit ‘Jack The Ripper’ (covered by The White Stripes and The Horrors amongst others) and provides a glimpse of a maniac at the height of his powers.

The Tornados – ‘Do You Come Here Often?’

(1966)

Something of a curio, this instrumental number from The Tornados is notable for its very camp voice over, whichh Meek later admitted was supposed to be two gay men meeting in a toilet.

While Meek’s homosexuality was hardly a secret to those who knew him, it caused him considerable personal misery and romantic rejection. Biographer John Repsch notes that he clamoured for a "normal" domestic life, which he briefly enjoyed after first moving to London, co-habiting with Lional Howard, a weight-lifting chef.

In late 1963 Meek was arrested for cruising in an Islington public toilet – homosexuality would remain a crime until only a few months after Meek’s death – an indignity that was followed by a public shaming in the London Evening News.

His prosecution for "importuning", for which he was fined £15 and received a criminal record, later led to Meek being considered a possible suspect in the still unsolved murder of Bernard Oliver, a 17-year old factory worker and rent boy known to Joe, whose dismembered body was found in a suitcase in Tattingstone, Suffolk in January 1967, ten days after his disappearance from Muswell Hill, North London. [The case features in Jake Arnott’s novel The Long Firm and was the inspiration for Coil’s ‘Boy in a Suitcase’]. Meek’s anxieties about being dragged into the police investigation exacerbated his already wild paranoia in the days before his death.

Glenda Collins – ‘It’s Hard To Believe It’

(1966)

We close with a classic Meek cut, featuring one of his favourite vocalists, Glenda Collins. Meek and Collins had a close working relationship; Collins admired Meek immensely, and Meek is said to have liked Collins enough to have at one point contemplated proposing a marriage of convenience.

This aethereal number, with its heady sense of impending doom, paints a picture of a man with too much on his mind. By this time Meek was habitually using uppers and downers to regulate his moods and keep his energy levels up – 24 bottles of pills were found at his flat after his death – with the result that his state of mind, already tending towards paranoia, became seriously delusional. He was sure that he was being bugged by rival producers, hearing clicks on tape recordings that nobody else could, and that black magic and radionic technologies were being harnessed by his enemies to beam destructive frequencies into his studio and control his mind.

Meek’s psychic storm had reached a zenith by the time of his and Violent Shenton’s terrible deaths. Who knows what might have happened had they been avoided, but the world was changing so fast that Joe may well have found a place for himself, and his incredible music, within it.

Cherry Red’s series of Joe Meek reissues began this month with The Telstar Story and The Heinz Sessions Vol 1.