Somewhere in the metaverse, a popstar echoes the loneliness of her LGBTQ+ fans during Covid lockdowns, as a smiley-face jellyfish floats through a Far-Eastern city. “I never knew,” says the voice of a fan, “How much I needed other people to feel alive.” In another utopia, a glitching, pencil-drawn, comic-strip boy holds out his hand to a bored girl in a café and pulls her into his universe.

Two very different music films this year unintentionally expose the delirious yet pernicious co-dependency between pop idols and their impressionable fans. The first scene mentioned is the opening of Charli XCX: Alone Together, directed by Bradley Bell and Pablo Jones-Sole. The second, of course, is Steve Barron’s iconic video of A-ha’s ‘Take On Me’, the 1985 sparkling, synthpop classic. The song plays on repeat through Thomas Robsahm’s film, A-Ha: The Movie, until the viewer is as haunted by this ageless ghost as its stars, grown men who wanted to be like New Order, but are doomed forever to play a boyband.

Both films reveal the cost of youth-led, summery music, that grand high of Charli XCX’s ‘Boom Clap’ of early love, from the 1980s to the 2020s – one through a mask of repression worthy of Scandinavian cinema, the other gurning through Zoom hangouts and Instagram livestreams. A-Ha: The Movie is a fascinatingly grim portrait of Pål, Magne and Morten, the exquisite comic-boy-lover who bequeathed ripped jeans to the world. Despite admiring critical re-evaluation by artists from Leonard Cohen and Coldplay to Kanye West, they find themselves lucratively trapped in their image.

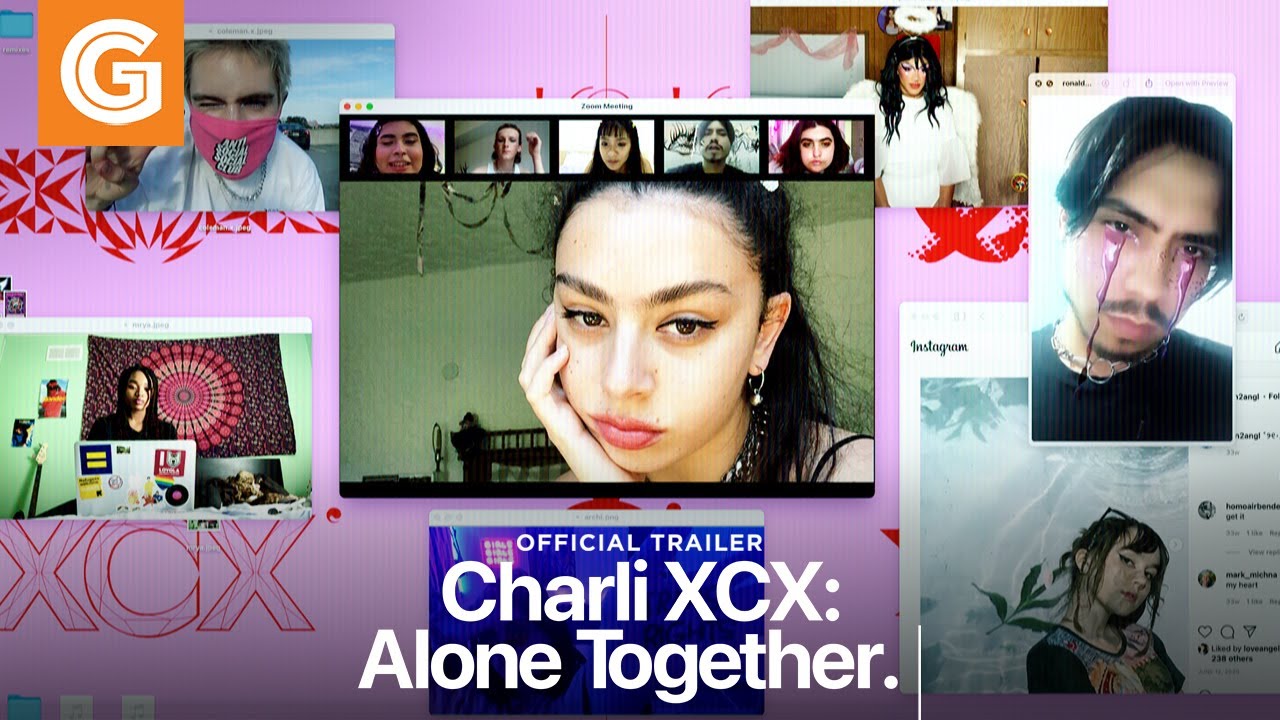

Alone Together, the lighter offering, presents itself as a D.I.Y documentary, filmed largely on phones. Charli XCX, the likeable, talented, gritty electro-punk-hyper-pop star, promises to make an album with her fans in 40 days, under lockdown. Unfortunately, in an industry supposedly driven by fan clickbait, this film feels it needs to be something more sensational. Haphazardly, it emulates the new breed of confessional music memoirs, pitching Charli’s mission as a way of improving her mental health. But by aping films like Demi Lovato: Simply Complicated, or The Jonas Brothers’ Chasing Happiness, the film reveals more about their queen’s use of her fans than perhaps anyone intended.

Pop has a tradition of LGBTQ+ fanbases passionate about straight dancefloor divas (Beyoncé, Britney, Kylie, Madonna). At one point, Charli bursts into tears of gratitude, on stage, to a euphoric response from fans. When they film themselves in their lonely bedrooms, they shine, these open-hearted queers. But not once does the film deliver a private moment between a fan and Charli. When she crashes a virtual Charli XCX party, fresh-faced and casual, it’s a royal P.A: no chat, just, “Do you want to hear my demo?” For all her punk-pop ‘Vroom Vroom’ IG realness, the hierarchy remains. Charli says the self-confidence of her LGBTQ+ fans enables her to express her vulnerability.

In fact, she has no problem narrating her self-loathing in phone videos, posting about her anxiety, the fear that she’s a terrible person (paining her boyfriend and mother but carrying on, regardless). At one point, she seems to be fishing for trauma, blaming the subconscious of her stalwartly supportive dad, because he was adopted. Does such Insta-reel ‘suffering’ equate to the vulnerability of one fan, for example, a queer brown drag artist ostracised in homophobic South America? I’m not sure, but the fans lap it up, creating a mutual panic room of trauma and healing.

The rise of on-screen trauma has been criticised this year with the hugely popular Euphoria provoking a rush of excitement and anxiety in its viewers. Alone Together isn’t about sexual assault but we see Charli crying, Charli lying paralytic with anxiety (but still talking and recording it). Panicked cells of screens proliferate: Covid on TV news; a doctor demonstrating how to breathe; the sobbing, mascara-running livestreams of Charli and her fans.

This trip, in its IG-friendly palette of lilac and cappuccino is distressing yet blissful, heightened and real. This is the same mingling of melancholy and euphoria that makes Charli’s electropop, and indeed A-Ha’s influential synth-pop, so intoxicating.

A-ha’s songs rise and fall like the North Seas, surfing on Morten Harket’s yearning, angelic voice. With their sad-sunshiny synth, ominous reverb and revving guitar, A-Ha sounded nostalgic before they became ‘80s nostalgia. They were – and still are (their 2015 album Cast In Steel debuted in the UK charts at No.8) – the romantic sound of what was lost before it was found. How fitting, then, that Magne, composer of ‘Take On Me’’s joyous, forward-travelling, earworm synth riff, should be made ill by the stress of being in this band. Forced by Pål, his childhood pal and self-appointed band genius, to give up guitar and learn keyboards (because the guitar was Pål’s instrument), he never receives the full song-writing credits he deserves.

Pål and Magne’s brooding friendship is one iceberg diplomatically submerged in the documentary’s quiet tragedy. Visually, a-ha: The Movie makes the most of the chilly spaces it uncovers in the band’s isolated green rooms and the limo where Morten travels alone – not for Covid reasons but his own sanity. “It’s my cocoon,” he says, quitting fans clamouring for his photo, his hands, his touch. It’s not only his fans he wishes to avoid. Once upon a time, Morten Harket, Pål Wakter-Savoy and Magne Furuholmen were three Norwegian schoolboys who decided to become megastars from a London bedsit, and did it. Now, they’re unable to write in one room together, without stirring up “a hornet’s nest”.

Robsahm’s portrait draws its grim energy from the trio’s toxic silence, dwelling on the emptiness of whale-grey backstage corridors, where placards announce one dressing room for Morten and another for the rest of the band.

Grizzly-handsome, the men speak phlegmatically in separate green rooms. Robsahm’s access feels guarded, each band member talking alone with him, their sombre faces enhanced by the beige and black corporate comforts of their tour. There’s no drink or drugs, no sex and rockn’roll. The effect is bleakly riveting. Robsahm tells a tale of lost love – the band’s love for each other – with CGI snow flecking the screen. With limited pre-internet footage, he segues his narrative with pencil-drawn animations that evoke the ‘Take On Me’ video. Morten’s honeyed beauty in old performance footage is breathtaking, tugging on our sense of lost better days.

Like Shakespeare’s Cleopatra, age has not withered Morten Harket, nor made stale the infinite variety of his posings. At 62, splayed like an old fart on a sofa, smirking at himself in the mirror, or embalmed in his limo, Morten accepts his burden of beauty. While Charli XCX makes her image in a time of diverse bodies, Morten hails from the era of invulnerable supermodels. His slanted cheekbones and faraway Viking eyes are as magnificent as the ethereal instrument of his five-octave voice. When, during a concert rehearsal, he folds his catlike limbs to settle, sphinxlike, on the edge of the stage, Robsahm’s camera is transfixed. Though the band rue marketing their looks, Morten grits his teeth and checks that his minder has his sunglasses and black leather jacket. It’s painful to watch him bearing Robsahm’s lens. Every second the star says nothing, we press forward towards his gleaming, godly eyes. What lurks in their deep blue? Is it rage, exhaustion, or is he thinking about the plants in his greenhouse at home?

“It’s very hard, as a photographer,” says Just Loomis, a-ha’s photographer since 1985, “When people don’t want to be together”. Robsahm, however, utilises the physical discomfort between the three men, Morten stoically occupying the spotlit centre.

While Charli XCX reports her upset to her fans continually, A-Ha recognise their fatal mistake of framing themselves in that iconic comic-book panel video, attracting the lemon sherbet fizz adulation of children. But they cannot agree on a mode of escape.

“We were all sick of that teenybopper style,” says Pål, praising the stylistic departure of their 1990 prog rock and blues influenced album, East of The Mountain, West of the Sun. But Magne feels it was “dishonest” and felt crushed under Pål’s “heavy hand”. Whatever Morten thought, he wrapped his new long hair in an Americana headband and got on with the show.

a-ha: The Movie is a poignant Faustian fable. But though Morten, rephrasing Keat’s sonnet, says “fuck fame”, the band, for all their love of New Order, Soft Cell and The Doors, seem too mired in their success to do anything else. One feels the limits of Robsahm’s material, at times. Though it’s a good moment when Morten finally flies off the leash, it’s a fleeting one. But watching him hold a high note for the longest time in recording history (20.2 seconds) in ‘Summer Moved On’, in a packed stadium, backlit by electronic fireworks, you have to wonder, isn’t this what teenage fans want, even now? Music that sweats tears and flashes fire? For summer to never end.

Alone Together is out now. a-ha: The Movie will be released on May 20