On February 4, Black Country, New Road release their second album Ants From Up There. Coming exactly twelve months after their Mercury Prize-nominated debut For The First Time, the album’s main deviation from its predecessor is that vocalist Isaac Wood is now actually singing. When Black Country, New Road released the one-two punch of singles ‘Athen’s, France’ and ‘Sunglasses’ in 2019, the fact that Wood delivered his lyrics in sprechgesang – "spoken singing" – cemented the popular notion that this technique had now become the dominant stylistic form for a certain type of British or Irish alternative act, which included Working Men’s Club, Dry Cleaning, Fontaines D.C., Shame, IDLES, Sinead O’Brien and, to a lesser extent, Squid.

That BC,NR have moved on from what was a defining feature of their early work is suggestive of two things. Firstly, some of the function of their work has changed – the new record is made up almost entirely of love songs, which presumably warrant the application of different techniques – and secondly, it’s implicit that this vocal style has possibly reached a saturation point in contemporary British guitar music and the band realised they were in danger of becoming permanently associated with what is fast becoming a sonic cliché.

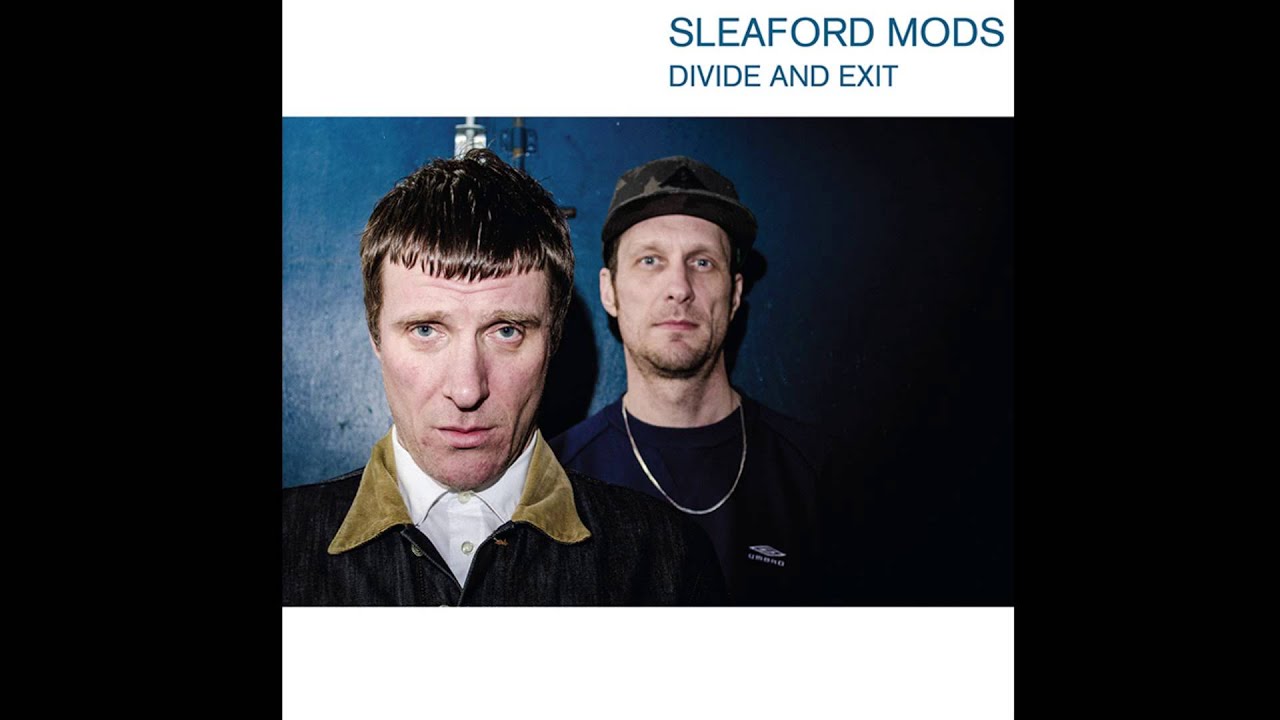

Artists that use sprechgesang now fill the BBC 6 Music airwaves and the larger stages of rock festival lineups. It’s become a feature of how British music is perceived internationally. "There’s a thing I love happening in the UK right now," explained US super-producer and Bleachers songwriter Jack Antonoff to Relix last year, "which has these sort of Lou Reed-esque spoken word verses with super melodic choruses that all these bands are doing… it’s coming hard and that’s not something you would have expected x amount of years ago." Though obviously sprechgesang is not a new innovation – the innovation has been credited variously to Humperdinck in 1897 and Schoenberg in 1912 – its current vogue can probably be traced back to the 2014 release of Sleaford Mods’ Divide And Exit.

With a bit of distance now, Divide And Exit can be clearly seen as one of the most influential British releases of the previous decade. Jason Williamson has evolved significantly as a lyricist since then, but that record’s densely packed aggro poetry not only felt fresh, it also chimed with the changing demands of listeners in the 2010s. So-called British alternative music had been politically quietist to the point of amnesia in the early ’00s – seemingly to exist on a separate timeline to, say, the Iraq war. Over the last ten years, however, the shock caused by a new Conservative government, austerity and the 2016 EU referendum seemed to force some kind of sea change. As a performance technique, sprechgesang provided bands with a powerful vehicle – a formal solution to the problem caused by the vocabulary of politics feeling jarring when sung. Sprechgesang counteracts the earnestness implicit in melody, shrinking the distance between vocalist and listener. It seemed particularly useful as a lens through which national decline or personal anxiety, or, even better, some combination of the two, could be observed. While not coming from the same place politically, Black Country, New Road’s Isaac Wood was able to use sprechgesang with brutal effectiveness nonetheless. It was wielded like a Swiss army knife of literary techniques, allowing him to deploy unreliable narrators, modernist shifts in narrative voice, and metatextual pop culture references, all with stunning impact.

That many of these acts enjoyed a commercial breakthrough seemingly did not pass indie musician James Smith by. Smith spent most of the ’10s in the post-punk influenced Post War Glamour Girls, with their third and so far final album coming out in 2017. Smith formed Yard Act in the autumn of 2019 with Leeds musicians Ryan Needham, Sam Shjipstone and Jay Russell. "About ten years ago, we were doing post-punk when it wasn’t popular," Smith told Louder Than War, "and maybe we saw a bit of gateway out when IDLES opened the floodgates, with Shame and Fontaines D.C. the other big ones that came through. We kind of knew there was a scene for it again and probably thought, ‘Well, we can fucking do that, [even though] we know that’s not what we are’. We’ve said it in a few other interviews. We definitely Trojan Horsed it, to get a bit of attention [off] the back of some of those groups but knowing we were gonna subvert it and move away from it as soon as we can. Which sounds quite cynical."

Though the band had only performed a handful of shows before the successive COVID-19 lockdowns, 2020 single ‘Fixer Upper’ broke through to become a minor 6 Music hit – the track was a polished, relatively polite reading of British post punk and satirised a seemingly Leave-voting, buy-to-let landlord, macho pub bore cypher named Graeme. That single’s success led to a deal with Island Records in the summer of 2021. Releasing debut album The Overload, Yard Act have spent January blazing through such milestones as the BBC Sound of 2022 list, Later… With Jools Holland and plum features in what remains of the English music press.

Across a brisk 37 minutes, The Overload paints in much the same colours as the nervy and proficient post-punk of Fixer Upper – even resurrecting that song’s narrator Graeme for the album’s indie disco-ready title track and lead single. "If you don’t challenge me on anything, you’ll find I’m actually very nice," mugs Smith as Graeme – there’s even meta advice from Smith’s creation to his band, offering, "Don’t be doing originals, play the standards and don’t get political." Though Graeme’s second outing in song, the character remains a caricature – one that’s particularly close to Steve Coogan’s townie character Paul Calf – and an early sign that The Overload may suffer from an imagination deficit.

The album has been praised for bluntly confronting post-Brexit Britain, but why does the country it describes feel curiously unmoored in the present? Outside of a reference to "fake news" that might have felt urgent half a decade ago, almost none of its observations and namechecks couldn’t have been written in the 1970s and ’80s. (These are also the decades that this record slavishly apes.) If this is meant to suggest that British public life has been trapped in a feedback loop since that point, then Smith never makes that case explicit. There are references to the National Front, the middle class growing their own lettuces, and kids out on the streets sniffing glue. With no disrespect to what I hope remains a vibrant and inclusive solvent abuse community, these are not references whose vivid specificity conjures life as lived in modern Britain. Unlike sprechgesang contemporaries Wet Leg, the band’s line in surrealism never quite lands – a scattershot reference to right-wing culture as "knobheads Morris dancing to Sham 69" sounds like it would make a pretty good Jeremy Deller short film.

‘Dead Horse’, complete with heavy-handed Lynn Collins ‘Think’ break pastiche, is Yard Act’s state of the nation address – comparing perfidious Albion to, you guessed it, a dead horse – but it’s too mired in familiar imagery and dead metaphors to deliver any killer blows on target. This should be important if, as Smith sings here, you take seriously the idea that England "does not realise it has already sentenced itself completely to death."

Both ‘Dead Horse’ and ‘Pour Another’ deal in stock liberal generalities – "The press have normalised the idea that racism is something we should humour," "I’m not scared of people / Who don’t look like me, unlike you" – that do plenty of telling but very little showing. You can feel ‘Pour Another’ visibly relax as it arrives at its inevitable chanted outro. Elsewhere, a guest appearance from the excellent Nottingham musician Billy Nomates – who elevated 2020 Sleaford Mods’ collaboration ‘Mork And Mindy’ to one of their strongest singles to date – somewhat lifts ‘Quarantine The Sticks’, which deals not with COVID-19 as the title might suggest but a happy-go-lucky embezzlement fraudster.

Hand-wringing liberal tokenism was antipathetic to Mark E. Smith, and the influence of The Fall is a contentious part of Yard Act’s genetic makeup. Reviewing the album in The Guardian, Alexis Petridis correctly points out that single ‘Rich’, with its "hypnotic two-note bassline, percussive clatter and distinctly Mark E. Smith-ish vocal intonation – ‘Skilled lay-BUUH in the private sec-TUUH’ – sounds so much like The Fall circa Perverted By Language you start wondering if it’s actually a knowing double bluff." But the idea that James Smith is playing some kind of cosmic brain 3D chess feels like a charitable reading when considering an influence that sounds derivative to the point of parody. In flaunting this influence the band seem to misunderstand The Fall frontman as a ranting lefty social realist, when he was a relatively conservative but formally inventive pulp horror visionary.

With widescreen production values and a six minute runtime, it’s ‘Tall Poppies’ that’s the most ambitious entry on the record. Much like the Kinks’ ‘David Watts’, it’s a portrait of a popular local figure – captain of the football team, the most handsome in his class – that, for its first half, feels like another of Smith’s borderline patronising character studies that have populated the rest of the album. It zooms out, though, revealing the fictional subject to have died of cancer, that he was a friend of Smith’s, his funeral is recounted. "He wasn’t perfect but he was my friend," speaks Smith, "He wasn’t perfect but it was one of us."

This homily is presented as part of a larger message that the album is striving to articulate. "I’ve become quite defensive over Graeme," explained Smith to The Guardian, adding: "He’s just a bit of an idiot really, with a lot of half-formed opinions he thinks are gospel. He’s an amalgamation of friends’ dads and men in the pub when I was growing up; they’re rife in small towns. Ultimately, if we can’t figure out how to coexist with the Graemes of the world, we’re not going to get anywhere." An admirable sentiment perhaps, but it makes for particularly boring art and, possibly demonstrates the suspicion that, when pushed hard, liberalism always falls to the right.

Sequenced close to the album’s end, the track fills a similar function to the stand-up comedy trope of an emotional or traumatic truth aired close to the set’s end, giving the hack illusion of narrative arc and emotional satisfaction even if the preceding material has underwhelmed. Promotional material for the album is keen to point out that the ban’’s aim is to "poke fun at society without punching down from a place of lefty superiority." This seems designed to pre-empt and counter the kind of critical response that followed IDLES’ 2020 single ‘Model Village’. Accused of being "patronising" and trading in class stereotypes, the band have subsequently confirmed that they will not perform it again – the pesky work, no doubt, of what IDLES frontman Joe Talbot referred to onstage recently as "pseudo-intellectuals masquerading as journalists."

In any case, critical response to The Overload has been overwhelmingly positive. Writing in The Times, critic Ed Potten outlined that in "their overcoat-wearing singer, they have a northern antihero with the ranting obstreperousness of Mark E. Smith, the angular intensity of Ian Curtis and the saturnine wit of David Thewlis in the film Naked." Whilst it’s hard to imagine Thewlis’ Johnny character saying anything as bloodless as "The last bastion of hope / This once great nation had left was good music," the comparisons garnered by Yard Act can often reveal a misreading of a certain strain in British pop music.

In his review for NME, Thomas Smith said "the band’s witty streak has more in common with Notts renegades Sleaford Mods or even Pulp and it’s mercurial frontman Jarvis Cocker." But Pulp were more than just observational writing set to indie disco, they throbbed with queasy sexuality and had a sharp-eyed complexity when it came to class. When Self Esteem’s Rebecca Lucy-Taylor writes about relationships or lust, I hear far more of Jarvis Cocker’s sensibility and lyrical eye than I do in Yard Act – Lucy-Taylor is never compared to Cocker, though, because she’s a woman, unlike seemingly every single British male lyricist who has jotted down a two-line character portrait on the back of a beer mat.

In their reliance on archetypes, their convenient adoption of influences and the undercooked limitations of their sound, Yard Act’s The Overload skirts perilously close to approaching a kind of landfill sprechgesang. When the journalist Andrew Harrison first used the term ‘landfill indie’, it was in a 2008 album review of the Swedish musician Jens Lekman, saying his music "resembles an al fresco health farm next to our own blighted landscape of landfill indie." Harrison’s term was apposite and proved sticky – used, sometimes unfairly, to describe the effects of the goldrush which followed NME‘s so-called New Rock Revolution. The major labels moved in and ill-prepared bands were fattened up and sent out to market. Bad bands can toxify the good by speeding up the process by which a genre becomes exhausted or defined by cliché, the half-life of interesting early acts like Franz Ferdinand or the recently reappraised Long Blondes becomes diminished by association.

This time round whilst some of what is happening is due to a much older story about corporate co-opting of independent music, some is also shaped by the pandemic. Live music having been in stasis for two years provides dire conditions for newness to flourish. People did not meet, new projects did not come together, A&R people were unable to do the work of going out and watching new acts. Yard Act have a sound with an obvious audience base, a newsy post-Brexit hook and in interviews make much of their underdog status. They are presently on course to hit the top spot in the UK album charts.

Elsewhere, sprechgesang still has plenty to offer in artistic terms. Last summer, Self Esteem’s single ‘I Do This All The Time’ – named The Guardian‘s best song of last year – broke through commercially, first gradually, and then suddenly. Something of a sleeper hit, from May to July it seemed to spread like a contagion around friends, particularly women, in my life. I had conversations about the song that were illuminating about people close to me. As a male listener, I was not let off the hook – Had I ever made anybody feel like this? Had the best night of my life been the worst night of someone else’s? The song’s power comes directly from its spoken verses – Lucy-Taylor’s voice feels conversational and direct, it evokes the self-help culture that it comments on. Its form and function were linked.

In Jack Antonoff’s earlier quote about sprechgesang in Britain, he specifically praises Self Esteem. North-East band Benefits have spent the last two years releasing work which used spoken word alongside ideas from musique concrète, industrial and noise – often written, recorded and released quickly, the songs felt like automatic dispatches in dialogue with their specific moment. So we shouldn’t be in a rush to bury the sprechgesang mode. The problem, instead, lies with bands who are talking loud but have little of use to say.