Yuletide portraits by Emma Goddard

I am the sort of person who can forget it is Christmas on Christmas Day. Although I am open to revelry and religious belief, institutionalised or spontaneous, I encountered hard-earned cynicism before wistful credulity regrettably early in life. The talcum powder wrapped up in an otherwise empty box of trainers was not the work of Santa Claus, my Mother had no use for Christian rituals, and my Father, a fair but ungiving man, had a thing about “false jollity” and held adults in fancy dress in contempt. My first Christmas memories relate not to our home, but seeing pretty lights decorating a small country town we drove through to visit relatives in the New Forest, a world away from the Christmas I inhabited.

Growing up I desperately wanted my parents to pretend it was all true so I could too. This meant that although I never felt the tingling, excitement and joy of a true believer, I never became a member of the party of Messers Scrooge or Grinch either. Instead I decorated my room in tinsel, sent out Christmas Cards in November, and waited to be filled with the magic, much to my Mum and Dad’s bemusement. Yet my enthusiasm never quite got me as far into the spirit of things as I would have liked. Over the years my Christmas became comparable with those reports of battle that confuse the name and whereabouts of the action, warped in a distorted sense of time, familiar and unfamiliar faces dropping in and out, where everything from the tree to the duration lasted too long after the occasion to qualify as an “event”.

But even in the midst of trying too hard to enjoy myself, “something” did occur, even if it did not happen to me. It was a “something” that I wanted more of then, and later wished to recapture; an ineffable and perhaps imagined memory of security and belonging. This, for me, is what at heart Christmas music is or should be, even if in practise it tends towards ersatz gimmickry, pertaining not to human feeling but a contrived event that is a substitute for it. It is no accident that the first Christmas song I voluntary came to, at The Woolworths on The Edgware Road in December 1987, the predictable one I am afraid, was one of remorse and exclusion from the joy others were feeling. “Real” Christmas songs did less for me than I would have liked then, and little for me now.

Yet the desire to be within heating distance of the fire is a feeling that endures, especially as I now have a family of my own. I want to take the turkeys at their own estimation and see what makes them tick, not as a sceptic but as the proselytising convert in waiting. For me a Christmas song is not an easy target, more a feeling that I wish I could connect with so as to feel less incomplete and detached (which is perhaps the natural condition for a critic, unenjoyable as it is to recognise this in oneself).

I start at the shallow end as Blondie seem about as orientated for Christmas as I am, which is my first mistake, as their Yuletide Throwdown EP is based upon a seasonal version of Rapture given away as freebie back in the day. Re-releasing it as a 2021 Cut Chemist remix is wholly on them though, a lazy mistake committed in the cold light of day. Elevating a spoof skit to a level where it may invite unfavourable comparison with a classic – literally ‘Rapture’ without the rapture – is squeezing anaemic pips out of pulverised fruit and hoping you’ll be left with juice. As Fab Five Freddy raps through a box ticking exercise of seasonal tropes, slow and exhausted by all those lists he has to remember — "Christmas time – once a year!" — Debbie stays on the edge of things, threatening to float away and pretend it has nothing to do with her, the spectral echo in her voice a supernatural disclaimer for this non-song.

No one needs to be told where Nat King Cole stands in relation to Christmas. Like Sinatra, who is also good at this kind of thing if you like it, he has a voice that becomes interchangeable with the objects and moods it refers to. Whereas some hear smug self satisfaction, gliding incuriously across surfaces, I encounter his voice as the effect of a deeper quality, a smooth veneer for suppressed insights, that smothers and smoothly asphyxiates all before it. At such moments Cole croons with the sage inner wisdom of one who is actually singing about something else, known only to him. The spell he casts by never breaking character once is interrupted on Sentimental Christmas by mixing his original standards with newly recorded contributions by various contemporary entertainers. While this is not quite as uncalled for as the Widnes Vikings slow releasing a group-fart into an already warm bath, these are not “duets”; rather rude interruptions. John Legend, in particular, goes well out of his way to demonstrate that the modern variation of overproduced sincerity simply cannot hold a Christmas candle to the 1940s variant, which at least sounds genuinely at peace with itself.

Lyn Stanley is releasing not one but six singles to mark this most special time of year. I listen to the first, ‘Moonlight In Vermont’, which is consistent with her press release’s claim that she is a highly accomplished name in big band jazz. It is a delicate yet overcooked journey through skiing holiday cliches, which could be used to sell anything from chocolate to aftershave, and might have been sung by any woman this vocally gifted between the closing stages of The Battle of The Bulge, and Biden signing off on his infrastructure bill – “timeless” only in the sense that it is tired and dated. Pentatonix or PTX, are a Texan cappella band with “have a nice day” painted on smiles (which has me wondering what the true value of sincerity without free will is), and their fellow Texans The Butthole Surfers they are not. Evergreen is a Christmas album that tries so hard to not offend that it squeezes on ‘I Just Called To Say I Love You’ to be on the safe side lest anyone confuse them for persons of opinion and character. No one will wonder what they were like when they were (very) young, because they never were, their arrangements having all the spontaneity of a Mark Zuckerberg interview scripted by his own staff, the bodies of any suspected humans having long been snatched, frozen, and smuggled into deep space.

Kelly Clarkson and I at least meet as equals, neither of us having heard of the other, although 25 millions album sales mean more people have heard of her than they have me. Her handle on Christmas is not that much more assured than mine – she knows only what the seasonal songs that use the same formulas as hers tell her, which is of course a game of diminishing returns. There is the odd nod on When Christmas Comes Around to modernity (‘Christmas Isn’t Cancelled (Just You)’), but her trite take on tradition, if heard in a public space while experiencing another of life’s seasonal setbacks, may just bring the number of shopping trips down this Yuletide. Meghan Trainor, A Very Trainor Christmas, is more evidence that reality is multi dimensional, a Christmas euphemism for, ‘Are they all fucking mad or are we?’ Meghan is a hyperbolically successful young American whose version of ‘Rockin’ Around The Christmas Tree’ makes Kim Wilde and Mel Smith’s version sound like Bitches Brew-era Miles Davis — which is unfortunate as her frightened and life-denying version of the track is also by far the best thing on the record.

Given that there are no surprises on Christmas records, and every failure need not be a disaster, it is disappointing that even a qualified shock – The Eagles Of Death Metal‘s A Boots Electric Christmas) – surprises only by conforming to existing tropes. There are no guitars here, or Sid Vicious’ ‘My Way’-style romps through ‘Silent Night’. Rather EODM sing the standards like a troop of wholesome Eisenhower-era carol singers, which at a time of year that is begging for variety, surprises with more of the same. The red-flag hovering over It’s A Cool Cool Christmas, a cult-compilation of alternative acts tackling the Noel-cheeseboard, is that crass Xmas cliches may simply be swapped for polite indie ones. If The Dandy Warhols and Snow Patrol taste no better to you than mince pies, their versions of the standards will induce double revulsion, whereas Grandaddy going ultra-wide eyed and hyper-naive to wish you a very hipster Alan Parsons Christmas, is them at their least necessary. There are some very pretty moments from Low, Teenage Fanclub and St Etienne, but the Christmas Classics have a hard-wired univocity that resists travelling too far from their received renditions. Like carols, these songs dislike change and dilution, which can often render novelty arrangements half-hearted and superfluous. Stay traditional and bore your listeners with more of the same, or go off piste with risible zany clownishness? Dull comes in at least two flavours, and Christmas is fraught with danger.

The Soul Santas (a west country supergroup featuring a member of Portishead) understand the limits of the brief, and the narrowness of the margins, so elect to go route one with a joyful twist. Christmas Crackers is a pub rock album of seasonal instrumentals, the different players coming together like a single noisy kazoo. Their agreeable din takes me back to a pub somewhere in West London where it is forever Boxing Day 1982. The grub here is always cold, the drunk guy on the electric organ falls off his stool, everything is paid for in ‘fivers’, the Sultans Of Swing are on next, and someone will sell you a Christmas tree, if you don’t mind the needles falling off “a little early next year”. Soul Santas soundtrack this Xmas of memory like they were there, which they were; this music is glorious, evocative, playful, serious and irreverent. It is Christmas as it probably never was, even then, and I love it.

Cliff Beach is similarly good value, creating an album of background music that demands a piece of foreground action. A self proclaimed “Nu Funker”, Cliff’s Merry Christmas, Happy New Year, is Yuletide spent in a superior Malibu beach condo where Sexual Chocolate’s Randy Watson sends up Jamiroquai as a party game, eventually finding it too ticklish to take anything seriously at all, before reverting to his own charming and good humoured version of events. Cliff’s warm and hospitable arrangements are immersed in stoned jouissance, peaking as he falls onto the floor in laughter with ‘You’re A Mean One Mr Grinch’, possibly then losing a little intensity as his thoughts and ours are distracted by what may be happening elsewhere in the room.

Gary Barlow looks characteristically serious on the cover of The Dream Of Christmas as well he might. Barlow is the seasonal equivalent of a cock-crinkling moment, guaranteed to put even the randiest off their strokes every December, so much of a stranger is he to spontaneity, good-will and genuine levity. With the predisposition of one who was born to vote Tory, and for whom a financial portfolio is genuine creative emotion, Barlow exhibits a sensibility which is incommensurable with Jesus Christ’s original message, which, fortunately for him, and sadly for us, is no set back in this game. He is the one artist featured here who I could imagine bringing a Christmas album out every year, without fear of censure or embarrassment, confident that not even his mother could tell the difference between them. When it comes to meaningless trimmings and po-faced renditions that pack the emotional punch of the narrator in a building society advert, Barlow is in his undisputed element, dispassionately attending to every commercial angle like a sniper covering the escape hatches of a burning building. One senses that after a while he probably does not even know what the words mean any more, singing in solemn slow motion to his imagined perfect listener, a tax haven, with the portentous gravity of saying nothing carefully. This is the true dark side of Christmas, the proper soundtrack to the lights that flash in call centres and the marriages that end in the kitchens of family gatherings. See you next year, yeah?

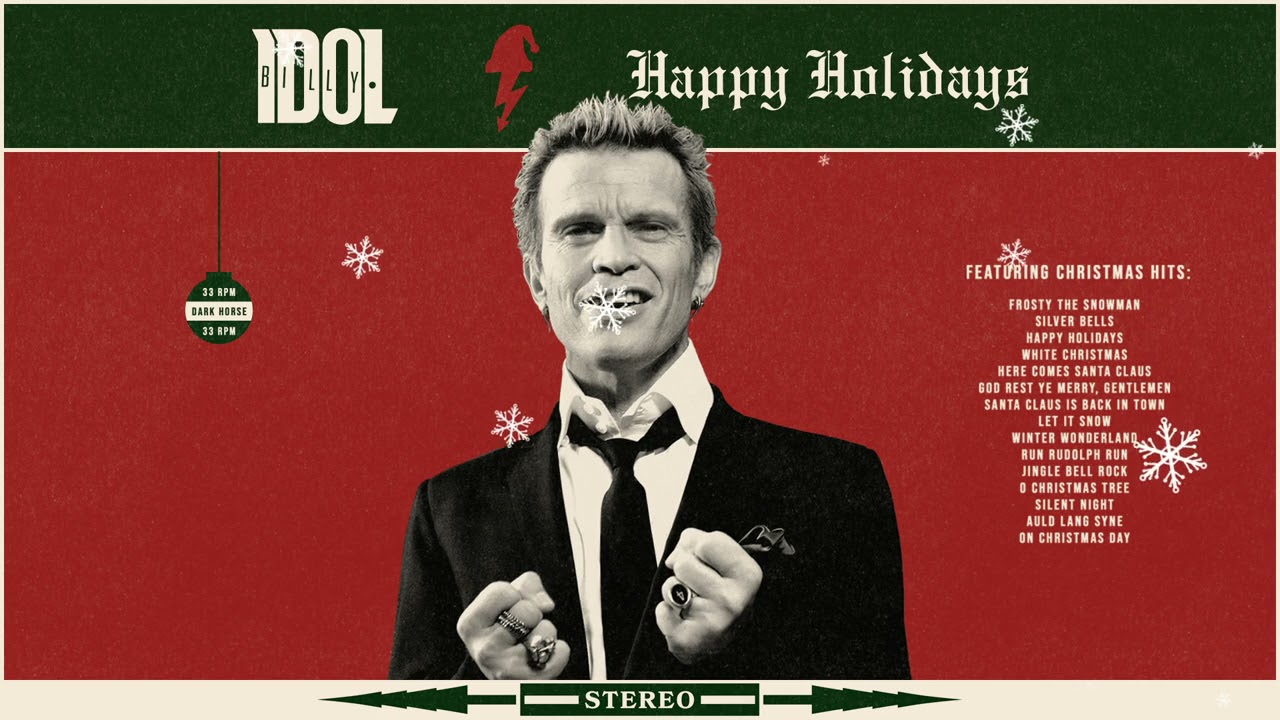

Billy Idol‘s Happy Holidays was the record I was most looking forward to, and like the later odes of Holderlin, is a lot stranger than you might expect. Idol starts in the only way the voice behind ‘Rebel Yell’ would be expected to, bullishly, going for broke on ‘Frosty The Snowman’ like he wants him to cry more, more, more. Eschewing howling axes for triangles and bells, the song is a Carry On Christmas-style piss take with a wink to music hall, full of fruity nudge nudges and spoken asides, which – unlike the awkward office party singalong it could have been – works because Idol sounds like he is having fun. He is a Bill Sykes that plays to the gallery and not to his demons. Unfortunately by track two he is beginning to grow a little more jaded, as if it is slowly occurring to him that just because we all grow old and still need something to do, that something doesn’t actually need to be this. Still, the realisation that a whole album of this stuff is going to be overkill, does not stop his version of ‘God Rest Ye Merry Gentlemen’ from keeping Richard Harris company in the astral bar that never closes, and ‘Auld Lang Syne’, a risk if ever there was one, is genuinely spooky, more Fagin watching the gallows being built from his cell than a new beginning in January.

There is a truism that all Christmas songs sound better sung by Tom Waits, and so it would follow that pretending to be Tom Waits singing a Christmas song must seem like a reasonable contingency plan. (It was clearly on the mind of The Flaming Lips when they covered ‘Silent Night’ for Cool Cool Christmas.) For most comers, this is still a degree of separation too far though. Ye Banished Privateers, “Swedish Sea Dogs” (with monikers like “Meatstick Nick”, “Monkey Boy” and “Old Red” — you get the idea) take the game-plan and walk right off the plank with it. A Pirate Stole My Christmas would like to come on like Rain Dogs-Era Waits, while actually owing more to Jack Sparrow and Gogol Bordello doing a Scandinavian Pirates Of Penzance. Like Billy they are undoubtably enjoying themselves (which is not something that could be said for every artist featured in this column, far from it), yet the rousing Christmas shanties and hearty thigh-slaps frequently straddle the not for everyone/not for anyone line, the Privateers falling the wrong side of it too often for it to be a coincidence.

Elton and Ed are the Butch and Sundance of Christmas, or the last stop before arrival at the Heart of Darkness, depending on where you stand in relation to their oeuvre. It was inevitable that they would get together over the big 25th as the architects of The Ribbentrop Molotov Pact would one day fall out. Both these giants are sincerity specialists, and if that quality were enough, ‘Merry Christmas’ would conquer all before it. Unfortunately they are a celebrity proposition, not a musical match, their resemblance to one another a wholly superficial one based on brand, sales and ubiquity. Ed is an enigma, what do they know of Ed only Ed knows, although even he may not have come up with an answer yet. Elton meanwhile is a maniac posing as an everyman, which might work as useful counterpoint to Ed’s everyman who is too shy to embrace the maniac within, if this were a wrestling team, but over a song the power lies too much with Ed (who wrote the lyrics).

Although there is some talk of this being a parody (a blend of every Christmas Number One ever to create “the ultimate Christmas number”), the two minute preview I hear is of Ed singing his verse and the chorus solo, addressing Christmas in name but not actually in spirit. Ed wants to reach the places only Cliff Richard (with perhaps a little help from David Grey) normally can, and would probably have been better paired with Chris Martin, a kindred spirit, than the Watford Mad Hatter. "So kiss me under the mistletoe/ Pour out the wine/ Let’s toast and pray for December snow" are lines that choose wistful sincerity and confidences by the campfire over the cheerful roar of a mulled wine piss-up that ends in the fireplace. A lost opportunity for them each of these men, as they could have at least had a little fun with the conceit.

Which can only raise the hope that Elton will think better of releasing his part — the Christmas purist in him ground down by commerce and emotion by numbers, and a lifetime contribution to both, deciding instead that the ultimate Christmas gift, if not Christian gesture (for lives exhausted by the responsibility of choice and invention) is the absolute absence of song this year — memory alone playing the tunes in December for an event we could hope, if not imagine, being celebrated in the divine peace of heavenly silence.

Merry Christmas.