“True creation comes into being only after the composer has discovered the spirit of the image,” wrote Croatian artist Tomislav Simović in a column entitled ‘The Composer And The Moving Image’ for EAR magazine in 1985. As well as composer, the Zagreb-based musician was also a member of several jazz bands and a pioneer of Southeastern European electronic music; he was, at that time, the only writer from former Yugoslvia to have contributed to that acclaimed American publication on new music.

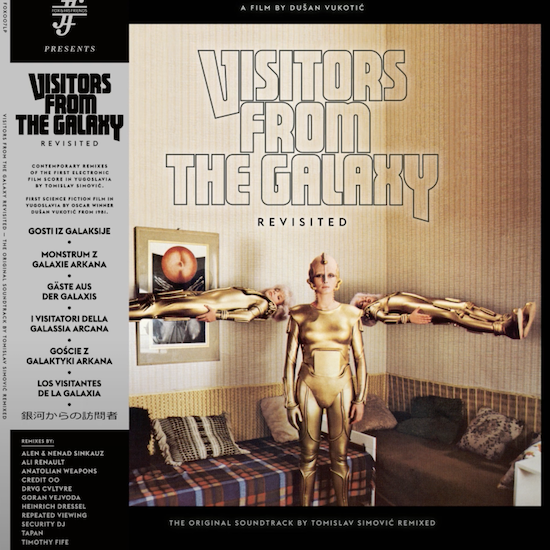

Simović was a prolific composer with over 300 film scores to his name, although most of them have been scattered and lost. He worked tirelessly and quietly, gambling that future generations of musicians would grasp the full complexities of his work. Three and a half decades after his appearance in EAR, the composer, who died in 2014, has recently received some validation from a future generation now that 11 contemporary electronic artists from 9 countries have reworked and remixed his pioneering experimental score to Visitors From The Galaxy. This music was the first Croatian/Yugoslav entirely analog, abstract, electronic and synthesised recording commissioned to soundtrack that country’s first ever science fiction feature film (which in another first, also featured a giant alien, whose costume was designed by non-other than Jan Svankmajer).

Simović composed music for the film as art – digging for psychological depth, instead of merely providing accompaniment to the visuals; he created an aesthetic gloss for the emotional interiors of characters while suggestively punctuating significant plot points. He was a true master of applied music and sonic arts, bringing them onto equal footing with the visual elements of film, maybe even reversing the sound-image hierarchy for some directors who came later. In short, his care for the sound of this film was exquisite.

Compositionally, he developed a curious richness of form whilst retaining refined outward restraint. Mindful not to interfere with the image the music was written to enliven, elevate and elucidate. Underneath his deceptively sparse atonal electronic experiments, unique auditory surrealism can be heard brimming over, brought on by a deep understanding of image-music relations utilising audio-visual elements to a higher-order of synthesis. With a dynamic hybrid of sources, he wrote musical themes as short sketches and layered them within a scene using a collage technique.

He mastered short form micro-dynamism to perfection during his work on animations while he worked at the famous Zagreb School Of Animated Films. He became known for the most famous piece of cartoon music in ex Yugoslavia, after writing the main theme to popular kids TV show, Professor Balthazar, while he was simultaneously venturing out into the avant garde (you don’t need to look any further than avant garde noise-fest ’Dnevnik’ for proof).

Collaborating with the trailblazing director Dušan Vukotić, Simović scored Surogat (1961), which won an Oscar for Best Animated Short Film, becoming the only Academy Award winning film in Croatian/Yugoslav history. This hilariously ingenious rumination on the various uses of inflatable beach objects was the first non-US cartoon to win the award, causing Walt’s ego to suffer a deflation during 1962, no doubt.

The Zagreb School’s mission statement was “to animate: to give life and soul to a design, not through the copying but through the transformation of reality”. During the Cold War it charted radical new Yugoslav alternatives, both socio-political and those of artistic non-alignment.

After their success with Surogat, the groundbreaking duo of Vukotić and Simović teamed up again for Visitors From The Galaxy. Even though it has since gained recognition as a cult classic, it was unfairly maligned at the time perhaps due to a wildly imaginative and audaciously genre-obliterating script from Vukotić (co-authored by Czech futurist comedy master Milos Macourek) and spent a long time culturally marginalised. Its eccentricities were a double-edged sword and earned it both specialised international festival awards and the local cinema-going public’s bafflement, not to mention critical chagrin. Stylistically puritanical critics, willing to priggishly overlook the film’s pure flashes of genius, would go on to consider it an abomination in the respective authors’ canons and misclassify it as trash. In truth, it is a hilariously weird and wonderful all-inclusive fantasy film (madder than a March hare and with a camp swag the size of the Arcana galaxy) made by a team of artistic visionaries with their genius on overdrive, combining sci-fi, horror and melodrama.

The film follows a wannabe sci-fi writer who has been afflicted with the powers of tellurgy and materialises characters from a novel he is writing into reality. They are a group of superior and benevolent humanoid aliens – Andra, an android superwoman (inspired by Maria, the maschinenmensch, from Fritz Lang’s Metropolis); the children Targo and Ullu; and the monster Mumu (which was quite unlike anything else from Jan Svankmajer’s repertoire) – and they appear in order to enthral their creator. They take over his daily life and create calamity in the sleepy seaside town where he lives.

There is estrangement galore, and surreal scenes that, once seen, cannot be unseen. The notion of gender is disrupted as a man breastfeeds. Svankmajer’s monster goes on a splatter-style killing spree, nudist locals welcome the aliens in an offer of peace and brotherhood, not to mention the first stirrings of an andro-erotic intergalactic romance. Oddly fresh in spirit, the film’s dynamics recall the surprise tactics of animation or even the contemporary oneiric logic of the visually-eventful and music-saturated style of contemporary made-for-Netflix series and music videos.

Science fiction here represents a radical affirmation of the imagination and art as a key force of transforming and pushing society as a whole forward, making it emblematic of the progressively utopian side of the Yugoslav spirit. But the true jewel is the score, successfully blurring the boundaries between music and sound. Simović treated all of the musical elements equally: a palette of rich sound effects; a sonic arsenal drawing equally from classical procedures, atonal experimentation, jazz and pop; showing no discrimination between so-called low and high culture. This is progressive popular modernism at its finest.

As a novelty considered a second rate replacement for live instruments, synthesizers were expensive and rare back then. While most musicians felt the new technology was beneath them, Simović had no such qualms. A smaller version of the first Polymoog and various machines he jokingly called ‘idiots’ were used for this score and when he played live. These ‘idiots’, under his masterful touch, actually showed a remarkable degree of refinement, and, perhaps unusually for the time, melodic prowess and atonal noise were balanced ideally.

Back then film music was a neglected category, denied serious critical consideration, but this in turn provided the freedom that Simović embraced. Though acclaimed both locally and internationally, behind his semi-reclusive pose, was a steely devotion to personal autonomy and artistic integrity, and he was well aware of genre limitations he’d have to subscribe to in order to fit into if he lived abroad. He strove “to watch life with my own eyes, writing music as I wish to, not as someone else wants,” according to one of his final interviews.

The Sun Ra mantra “Somebody else’s idea of somebody else’s world is not my idea of things as they are”, resonates deeply here. Simović did things his own way, which in turn was also in keeping with the Yugoslav spirit – that of personal genius being nurtured and kept possible within a specific social atmosphere. Tito’s famous refusal to Stalin is the key to understanding the unique Yugoslav experience, built precisely in opposition to the Eastern Bloc. That autonomist resistance marked the start of an unprecedented social experiment to radically transform the society post WW2 on the wings of the historic victory against fascism, a cornerstone for the Yugoslav creation myth.

I am concerned here with the positive phenomena and the conditions of social revolution that birthed the vibrant and popular modernist boom, best reflected in applied arts and design (as the recent MOMA exhibition Toward A Concrete Utopia: Architecture In Yugoslavia, 1948–1980 demonstrated). Beyond Western misconceptions of life ‘behind’ the Iron curtain, in its golden age, Yugoslavia was a fairly culturally liberal, hybrid socialist utopia. With the SFRY red passport that could take a Yugoslav as far abroad as they wanted (and in most cases without a visa), it was open to the world due to factors like a geostrategically favourable position, tourism and skilled diplomacy. Since the country I was born in ceased to exist – it was most violently erased – I no longer identify with the notion of countries. The nation-state mindset is a 20th-century perspective anyway, a collective identity anachronism incompatible with today’s global problems. That said, some of the former spirit has remained imprinted.

Visitors From The Galaxy Revisited (Original Soundtrack Remixed) is far from an exercise in aesthetic retrofuturist fetishism or of recycling the past and is even further from nostalgia for its own sake. Cultural memory must be seriously rethought, reevaluated and recontextualised, as the critic Željko Luketić and radio DJ Leri Ahel must have thought when embarking on a herculean diggers task to find, restore (at Cedar, Cambridge) and re-publish the languishing gems from Yugoslav’s golden era via their own Fox & His Friends label, based between Zagreb and Rijeka.

This exquisitely crafted and produced album, reworks and significantly re-imagines the OST, honouring the script, via sampling of the film’s most well-known lines. Producers were granted full freedom, but nonetheless, while working individually, they hit a remarkably cohesive vibe within a disparity of styles (IDM, acid, ambient, techno, electro) suited equally to the dancefloor as to the audiophile experience. Contributing musicians include Alen & Nenad Sinkauz, Ali Renault, Anatolian Weapons, Credit 00, Drvg Cvltvre, Goran Vejvoda, Heinrich Dressel, Repeated Viewing, Security DJ, Tapan and Timothy Fife.

These newly constructed minimal brutalist soundscapes are deeply magnetic, full of reflective digressions and fluid twists, and draw from the OST’s rich effects palette affording them newly augmented dimension and a massive heft, much different to Simović’s practice of layering minimalist audio sketches with sublime, soaring melodies. Heinrich Dressel’s rework honours the dominant melodic flow preserving some of the faith and optimism of the original. Operating in strange juxtapositions alternating between dystopian and utopian moods, old and new, positive and negative spaces, the reworkings, for the most part, bring a darker palette and club-friendly atmosphere.

Ali Renault’s End remix of ‘Main Theme’ most explicitly reveals the remote parallelism of two worlds, times and mindsets as not only chronologically, but ontologically separate realms.

The track stomps firmly forward on a steady earthy beat, haunted from the background by sequences of Simović’s original main theme, sounding almost incompatible as if quietly left to simultaneously play on a separate channel. While a superficial engagement might suggest a lack of cohesion, the conceptual contextualisation recognises the juxtaposition of remote perspectives as if preferring not to draw conclusions.

A deep reading of these atmospherics might find these new tracks more technologically advanced than the source material but still retaining a general sense of the austere stasis of our times. Still marked by a capitalist realist crippling of hyper-rationalisation, a repression of the unbridled imagination is inevitable. It is precisely the inspired, emancipated melody soaring to lyrical exaltation coupled with the inventive experiments of Simović’s OST marking the difference in times: popular modernist utopia juxtaposed with contemporary desolation.

The superbly enchanting OST ‘Main Theme’, giving off cosmic Morricone vibes, perfectly illustrates this utopian futurist flight of the imagination. A sonic spectre of the once manifest idea of Yugoslavia haunts our minds and ears still. While the reworked project cannot be described as hauntological in aesthetic terms, this new record preserves the eerie original blueprint of the utopian ideal. The future as an event yet to happen haunted the OST, as the now lost future haunts the reworking.

The future does not always come from directly ahead. This is a quizzical proposition sounding suspiciously hauntological, oddly disorienting, yet strangely inspiring for a progressively retrograde mindset, in opposition to the nostalgic-reactionary impulse. We turn back to tap into the unexhausted future potentials of the previous periods containing the seeds of the new. Revolution as a deathmatch between past and future, resistant to perpetuating itself, self-destructs in fear of slipping into the reactionary. The blind forward motion of the culture of replacement continues without advancement, progresses without evolving. It is a consumerist machine imitating the revolutionary form of overturning the old without actually delivering the future.

The concept of time has shifted, demanding a new logic of futurity. The future is no longer connected to historical time; instead it has been pushed from the realm of the empirical to a secondary virtual realm. Everything that gets displaced from history will come back to haunt you in the form of art. But art should help us build the kind of world we want to live in. Occasionally relics of the utopia we once lived in still linger on virtually. Infrequently utopias do materialise, but like a mirage, they shimmer and quickly vanish. They are transient reminders that a different world is possible.

The sonic dimension is especially receptive to preserving these echoes of the lost future, as equally as it is to catching the first signs of a new paradigm. Sound has an intrinsically social dimension, it occupies the liminal space between life and non-life and deals with the intricacies of organising inner social space. Aural bonds design and predate new social systems, from the inside out. Sound is the bridge between these two worlds, between virtual and empirical social spaces. But some confusion subsides when we shift the idea of defining the future from a temporal perspective to a question of paradigm shift. Simply, the future is the new paradigm shift. If you imagine a graph, there has been a vertical incursion of a new idea into the horizontal axis of temporality, a disruption serving as a game changer. The true socialist sci-fi question is really about alienation from the future – that is the malaise of going through the motions of time in absence of a new paradigm.

Isn’t all of this post-historical out of jointedness – all of this perturbation, reconfiguration and dislocation – merely a strange juxtapositional method by which we provoke the future, after all it exists through our relationship with it and never without our interference. Perhaps this interference will be welcomed by some distant guests from the past, that was once the future, now appearing to us again, like contact with an alien species.