In the 1982 documentary Say Amen Somebody, ‘Mother’ Willie Mae Ford Smith pays tribute to Thomas Dorsey, “The only one who would dare to make gospel music what it is today”. She explains how “he took the church music – spirituals, hymns – pepped ‘em up, put a rhythm to them and called it gospel.”

Before crossing paths with Dorsey – long-time musical director of Chicago’s Pilgrim Baptist Church, the “mother church of an entire genre” – Smith had been labelled a spirituals singer or revival worker. Just as founder Dorsey passed the torch to Smith, she would encourage progressives including the Barrett Sisters and the O’Neill Twins to share the good news in their own way.

One of the twins remembers in the film how gospel singers of the past were evangelists, and cautions how their generation often gets caught up on the making of a hit record at the expense of substance. It’s a fascinating debate – the distinction between worship and performance, the tension between the sacred and the secular.

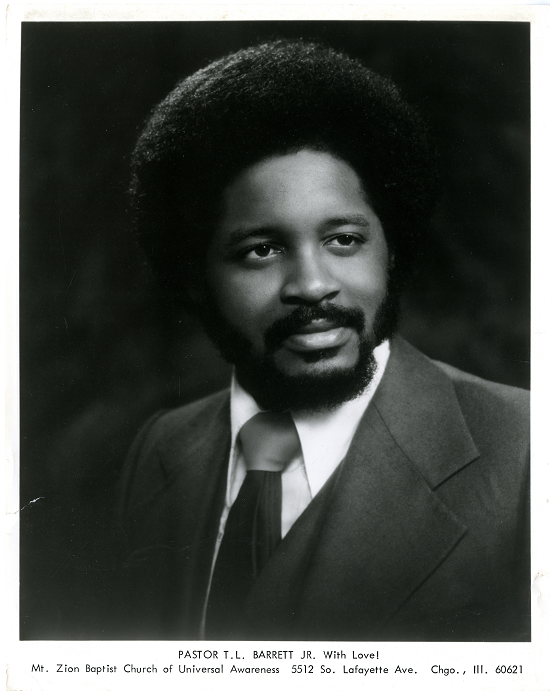

It’s a discussion that was in full flow in 1982, so imagine discovering a record made 11 years earlier, credited to a rookie pastor and his youth choir. A ‘gospel’ outlier that can hold its own against some the finest and most fervent soul of the period. What triggered such a bold and brisk evolution? “There’s some people … the spoken word just doesn’t do it for them,” Pastor TL Barrett told Chicago station WTWW last year. “But if you put music to it, [clicks fingers] you got ‘em.”

Speaking to tQ on the phone, he expands on that thought. “I would walk in the community, trying to bring the word to the people but they didn’t want to hear a sermon. But when I invited them to a get together, a youth gathering, they came. When they heard the music, with those same words I tried to share on the corner, they accepted it. ‘Like A Ship’ is just one example.”

New York-born Barrett had lived many different lives before he took charge of Mount Zion Baptist Church on Chicago’s South Side, where he would later minister to the likes of Earth, Wind & Fire’s Philip Bailey and AACM co-founder Phil Cohran. He had worked in a morgue, shined shoes, become a jazz singer and mostly self-taught pianist inspired by Errol Garner among others.

But being the distant cousin and former student of preacher and activist Reverend CL Franklin, father of soul icon Aretha, it wasn’t long before he heard the call. Misfortune also played its part. “My father passed away suddenly when I was 16, with no life insurance for us to live on,” he recalls. “My high school [Wendell Phillips Academy] had dismissed me shortly before that. One of the guidance councillors there told me I wouldn’t amount to anything.

“I remember walking from 39h and Giles to 59th and Indiana on the way to my sister’s house. I was like a ship … without a sail. But I knew I had some valuable cargo inside me. I made a pact with god, there and then, to keep my mind and body clean. To combat negatives by coming up with positives.”

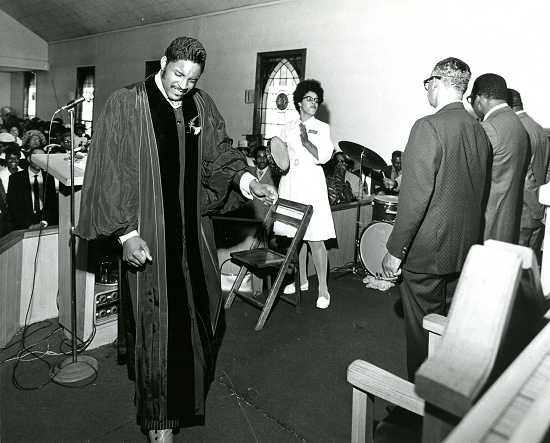

By identifying with their hardship and helping them look beyond it, the pastor was able to appeal to disillusioned youth. He gave them hope. “I would tell them, you are kings and queens. You come from royalty. That’s why we’d never call the children in our church ‘kids’. They are miracle-minded masters. I gave them a mantra: ‘I am a master, I learned it from my pastor, and I will never be a disaster.’ So you can’t do drugs, steal cars, rob stores, wreak havoc on your community…”

Mount Zion was located in one of Chicago’s most troubled areas, a place nicknamed “The Hole”. Pastor Barrett built on his sermons with grassroots activism at a time when Black Americans were seeking greater economic and political power. “Fred Hampton [chairman of the Illinois Black Panther Party] was killed by the police in 1969, which galvanised the Black community to challenge the entrenched hierarchy,” author Aaron Cohen, who contributes liner notes to a new T.L. Barrett box set, I Shall Wear A Crown, tells me.

“Violent crime had worsened into the early 1970s. there were also imposing public housing towers such as the Robert Taylor Homes, which were near Mount Zion… Pastor Barrett addressed these issues in his sermons, ministering in the projects and recruiting church members from them. He was also involved in local politics, providing forums for candidates, encouraging Black entrepreneurialism [not least by releasing his own records] and later hosting his own radio show [on WBMX].”

How, then, would this activism manifest in his conception of gospel, a sound anchored by tradition yet mutating in the ferment of Black struggle? One-time choir boy Curtis Mayfield had set the trajectory back in 1965 with ‘People Get Ready’, an R&B hit steeped in the imagery of The Bible. Then there was pianist Edwin Hawkins, whose arrangement of an 18th century hymn for the Northern California State Youth Choir crossed over in a big way as ‘Oh Happy Day’ in 1969.

The track featured a Latin groove, synthesisers and Dorothy Combs Morrison’s “good God” inflections inspired by James Brown. ‘Oh Happy Day’ won a Grammy the following year for Best Gospel Soul Performance but prompted criticism from certain quarters of the church.

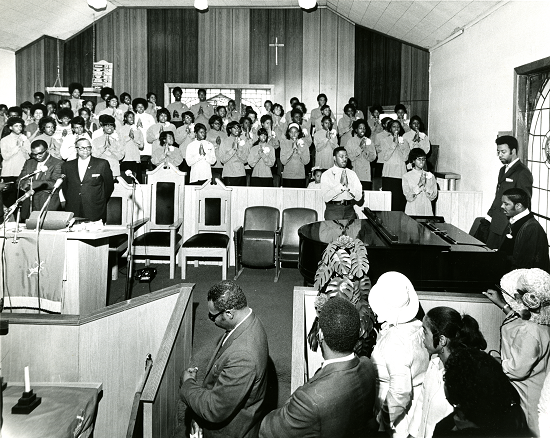

Pastor Barrett was also a songwriter and would develop ideas with his Youth For Christ Choir, a Tuesday after-school programme for children aged between 12 and 19. It caused quite a stir. Earth, Wind & Fire’s Larry Dunn and Andrew Woolfolk passed through; (the group’s legendary horns would later feature on Barrett’s‘Do Not Pass Me By’ in 1973). Donny Hathaway visited and pulled out his tape recorder.

The choir would often feature at events for Operation Breadbasket (later Operation PUSH), Jesse Jackson’s initiative to boost Black business, jobs and housing. This was crucial to the genesis of Like A Ship as house orchestra leader Ben Branch introduced Pastor Barrett to Gene Barge, a key arranger and producer at Chess Records.

Barge supervised the recording sessions at The Sound Market Studio, drafting in experienced players including Phil Upchurch and Richard Evans to bolster the church band. There were no egos in the room. “They saw the enthusiasm of the choir, the gleam in their eyes, felt the sincerity when they sang,” says Pastor Barrett. With Barge’s help he harnessed their collective potential.

The album bristles with spontaneity, and much of that is down to its chief architect. “He plays what he hears and writes what he feels,” states Reverend Edmond Blair – the pastor’s pastor – on the back of the original release of Like A Ship. Apparently critics have questioned the quality of the record because the choir aren’t professionals. He [Barrett] believes that one can do all the things through Christ that strengthens him. The Youth for Christ believe it also…”

Like A Ship’s calling card is unquestionably the title track, written in the pathos of the pastor’s turbulent teenage years. The purposeful rhythm of the intro, pure bass and drums, immediately sweeps you up as the electric piano twinkles and those sleigh bells shake along. But who would expect that resounding chorus to follow. The pastor describes it as “haunting”. It’s as if the choir is singing in defiance on the downslope. Then people join hands and clap as the drums roll and the bass undulates.

“I searched for pleasure. But I found pain,” he sings. “I looked for sunshine, yes I did. But I found rain. Then I looked for my friends. They all walked away. Through all the sorrow, you can hear me say … but I know you’re can make it, I know we can shake it…”

‘Like A Ship’ is an anthemic ode to perseverance – for the religious and the rest of us. It could serve as either rallying cry or crescendo, which is why the music supervisors of Crip Camp, the acclaimed Netflix documentary about the American disability rights movement, chose it as the coda to a remarkable tale of triumph against the odds. Covers by Beck, Leon Bridges and Richard Ashcroft have drawn in countless others listeners.

‘Wonderful’ is a subdued affair in comparison, but the message is equally positive as Pastor Barrett testifies how, “the Lord is my shepherd and my guide, whatever I need he will provide”. There’s such depth of sorrow in how he articulates the word “sad”. But then the choir counterpoints his lead at the high end, lifting the mood. You can see them standing right there behind him, giving him wings.

Where each element sits in the mix is part of the majesty of this record, its rush. Pastor Barrett is amusingly modest when I ask him about this, ruling out studio wizardry – “we just put the mics we you would put them”. Listen to ‘It’s Me O Lord’. Here the powder keg drums have that low-end punch, the piano steers the course while the chorus carries us up and away by our ears. And those claps, placed just to the side of you, daring you to cast off any inhibitions and join the congregation.

Sequencing is also important on Like A Ship, how the running order triggers a symphony of sensations. That’s down to “divine design” says Pastor Barrett. Upchurch gets to flex his bass on ‘Ever Since’ as the pulse quickens to four four and Charles Pittman’s drums start the stomp, readying us to chant those two words uncontrollably. Barrett initiates the call and response, declaring “I found him” with great conviction, telling us how the Lord’s been “soooo good”.

If there’s one song that can top the instant gratification of ‘Like A Ship’ and how it takes hold from the first beat, it’s ‘Nobody Knows’, which opens Side B. Again, the combination of rhythm section, piano and choir takes us from sublimation to salvation. Glory is a potent word and it’s a key one on this track. A way to get over.

“I been abused and I’ve been scorned,” he sings. “I been talked about, yes I have, just as sure as you born. This is a mean world to try to live in, but you got to stay here until you die. Without a mother, no no no, don’t even have a father, I’m lookin’ for my sister, I can’t even find my brother.”

As the pastor hums “hmmmm”, it as if he’s reaching deep down to that place you put your deepest pain, searching for answers. During a recent Tiny Desk performance, he gave context to this slave song (recorded by Louis Armstrong and Paul Robeson), and the weight of Black suffering it carries. It stretches all the way back to those hideous acts on the plantations and beyond to the hardship of those who have come through the projects like the pastor and many of his choir members. But “it’s not where you’re from, it’s what you made of yourself,” he reminds us.

The “nobody, nobody, nobody” outro is simultaneously eerie, sorrowful and yet exhilarating. The chorus builds tension and release with its waves of “oooooooos” and aaahs”. This is about as visceral as recorded music gets. Its kinetic, transformative power has featured in a Steph Curry sneaker commercial, the origin story, of the first Black president, and even a Black superhero series. DJ Khaled got the message, as did several other crate diggers.

‘Joyful Noise’ is dedicated to the pastor’s mother and the Mount Zion family, another Pittman-powered uptempo track that more than delivers on the title. We’re enveloped in its immense sound until Loretta Lake’s soprano cuts right through. Sometimes all it takes is a “Good Lord” here and there to take us higher.

Closing the album, we have a breezy medley incorporating heavy renditions of ‘I Love The Lord, He Heard My Cry’ and the ‘Lord’s Prayer’ – the pastor’s electric piano carrying the Cadet swing of Ramsey Lewis as he calls out to the choir. The soulful strut of ‘Blessed Quietness’ sends us on our way, Barrett emulating the percussive stride of Geraldine Gay accompanied by the sweet organ of Gary ‘Snake’ Riley.

“I was amazed he could play the piano, that’s what really turned me on about him,” Riley, who still plays with the pastor today at his "prayer palace" in Washington Park, says in the liner notes to the new box set. “He was just unique. More musically, because I was a musician, but he could preach and that was another thing that stirred me. A lot of preachers were just saying what they did last week. He never preached the same sermon.”

There were other churches and groups releasing similar r‘n’b and syncopated gospel in small runs around this time. Numero has released two compilations of them, “acolytes faithful to a spirit, but never to an ordained sound”. Into the disco era, countless other acts would follow. Over the past 20 years I have had several epiphanies to them – The Celestial Choir’s ‘Stand On The Word’, The Clark Sisters’ ‘Ha Ya’ ‘Ha Ya’ and Gloster Williams & Master Control’s ‘No Cross, No Crown’.

Meanwhile, producers such as Knxwledge and Alchemist have sanctified the headphone experience with deft samples of The Thomas Whitfield Company and The Fountain of Life Joy Choir respectively. But when it comes to conveying the exhilaration of a gospel gathering at the dawn of the 70s over two sides, Like A Ship is peerless.

I tell Pastor Barrett that so many giddy comments on YouTube are prefaced by disclaimers such as “I’m a die-hard atheist”, “religion isn’t my cup of tea” or “I don’t even like gospel music but”. What is it about Like A Ship that converts, captivates, invigorates so many of them? “There is a cosmic familiarity that supersedes the physical familiarity,” he says. “We have to sense each other through the five senses to develop the physical. That’s the god part of us, the soulful part of us, and the music helps us reach the soul. Our music is not about being a Christian. It’s about being alive, part of the miracle of life, and that’s experienced by Christians and non-Christians.”

Cohen, who thinks Like A Ship is the most significant Chicago contribution in the transition to contemporary gospel, homes in on its intensity. “The uplifting tone, the vocal delivery… people respond to that energy,” he says. “The songs also have hooks that’ll bring in anyone who grew up listening to different forms of popular music. Then you’ve got top session players. And the youth choir will appeal to anyone who was once young. So everybody, right?”

Indeed, there is a palpable innocence in the air. It’s endearing and infectious like on some of those raw schoolhouse funk recordings. Like A Ship captures an uninhibited, undeniable moment in time and the ecstasy of being in that moment. In a word, sacred.

A new 5xLP box set of Pastor TL Barrett And The Youth For Christ Choir’s music, I Shall Wear A Crown, is out now via Numero Group, and includes a reissue of Like A Ship You can find out more and order it here