Mark LaGanga is a cameraman for CBS’s 60 Minutes, but in 2001 worked for the network’s North East news bureau. I ask him to tell me everything he can remember, from the beginning.

“I was at home on the Upper West Side when my landline, cellphone, and pager all went off at once,” he says. “It was pretty unusual to have two of those three things at that time.”

In my conversations with 9/11 survivors, there is usually a moment at which they note the technology they were using. I read it as a grey-tinted nostalgic acknowledgement for anyone for whom 9/11 is a living memory of just how much change the world was experiencing at the turn of the century, and that that rate of change has accelerated in a way few of us expected, or desired.

The meeting of a particular technological and geographical moment is the reason why, for most people, although four hijacked planes crashed on September 11th, 2001, ‘9/11’ is culturally synonymous with the destruction of the Twin Towers in New York City.

The attacks in New York City were the first to occur, drawing immediate attention from the national broadcast news hub just districts away. Additionally, as a leading tourism capital and global hub for artists and the incredibly wealthy, even as camcorders had only recently become a consumer item, NYC likely had one of the highest camera per capita rates in the world.

As a result, the attack on the World Trade Center is one of the most recorded events of all time.

What is it like to hold a visceral record of one of the worst days of your life, and have everyone from nosy writers to conspiracy theorists fascinated by it?

The calls lighting up LaGanga’s new devices were from CBS’s national office – they needed someone downtown straight away to capture a developing accident. By the time he arrived on West Street and started rolling, the first tower had already collapsed. But amid the chaos and dust in the air surrounding the still standing North tower, LaGanga didn’t initially realise the South tower was missing from the skyline.

He went to investigate, and ended up capturing one of the few known records from inside the WTC complex between the two collapses.

“I’ve never figured out how it got online,” he says. “I don’t care too much because I don’t own the footage, CBS does, but somebody uploaded it from colourbars [the test pattern at the beginning of all TV broadcast tapes]. Either somebody recorded it off the satellite when we fed it into the broadcast centre, or somebody inside CBS did it.”

LaGanga also captured the only known footage from inside WTC7, another building in the complex across the street from the main plaza, and the third building to collapse that day. Back outside, he began to resume interviews with bystanders when the North tower began to collapse.

*

He stays put and captures the whole thing, from just metres away. For exactly three minutes in a pitch black landscape, he cowers with his camera still rolling. He then gets up, cleans his lens, and resumes interviewing people on the street.

“What happened?” he asks the first man to appear near him. The man is covered head to toe in thick white dust, and struggling to breathe.

“It collapsed…I saw it blow and then ran like hell….thank God,” he laughs. “I’m 69 but I can still run!”

LaGanga asks me if I ever found out what happened to that man; I let him know I tried and failed. I ask him if he had been offered any therapy by his employers, but he nonchalantly responds that no, he was immediately back on the job. This time, to Afghanistan.

He had previously reported from conflict zones, and though this was different, his home turf, he notes that those experiences “probably prepared me, as much as anybody could be prepared for that sort of thing.”

Throughout our discussion, he speaks as though 9/11 was just another day at work.

*

For interior designer Tami Michaels, it was a turning point toward a difficult chapter in her life. She makes clear that, though she knows the tape is in the public domain, “I am not promoting the tape, or advocating that people watch the tape.”

‘The tape’ has, unfortunately, become notorious in certain corners of the internet. As horrific as it is, it is a genuinely unique and powerful historical document, and has significantly influenced the course of her life since.

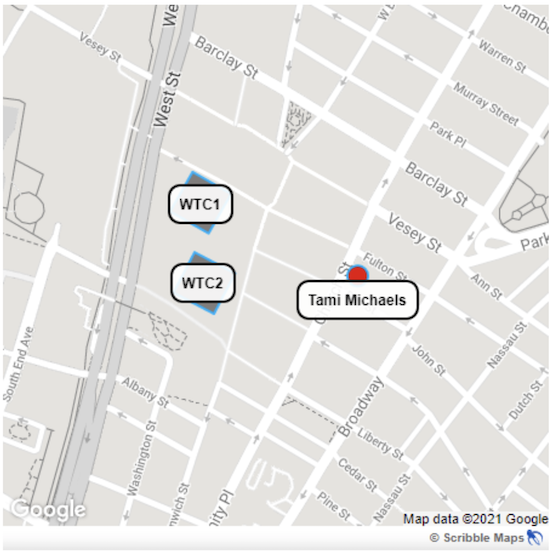

Michaels suffered “horrible PTSD” in the years after 9/11. Tourists in NYC armed with a camcorder, Tami and her husband Guy rode out both impacts and collapses from inside their hotel room on the 35th floor of the Millenium Hilton, directly across Church Street, with an unobstructed view of the WTC complex’s plaza.

As a result, parts of her tape show people jumping from the towers, just meters away. Distraught, the couple discuss what is happening in disbelief, and whether it is safer to stay or leave.

During our conversation, Michaels is incredibly frank; I acknowledge my ambivalence about making international calls to strangers to ask them about the worst day of their lives, but she anticipates all my questions. She tells me about her work in Seattle, her home improvement radio show and television appearances. She’s media-savvy.

The couple has been approached a number of times to sell the footage. “The amount of money that we were offered for the rights to this video exceeds six figures,” she explains – but so did the medical bills which accrued from the neck injuries Guy sustained when the fireball from the second plane hit their window. He hit the opposite wall headfirst.

“It would have made a huge difference in our lives, we’re not wealthy people. But it’s blood money,” Michaels says. They’ve never sold it.

Instead they turned it over to the FBI. It found its way online after being released as part of a government response to Freedom of Information requests – which is also how LaGanga’s footage ended up on YouTube.

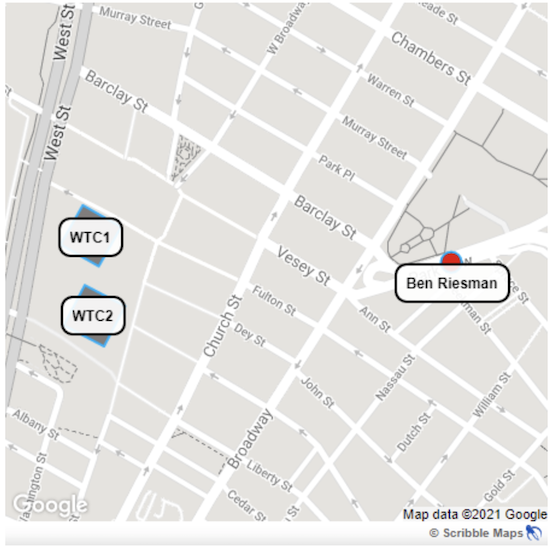

Ben Riesman was a young experimental video artist in NYC in 2001, and on hearing a skyscraper was on fire thought it could make for some interesting visuals.

He arrived at City Hall a few blocks away about 9:45am unaware this was anything but an accident. What he captured never made it into his work, but has been watched hundreds of thousands of times, both as raw footage online and in other people’s work.

“It’s weird that I’m famous in some strange corner of the internet,” he says. “So, have you actually seen my footage in conspiracy documentaries?”

I have. As a film student, I wrote a dissertation on 9/11 conspiracy documentaries and became familiar with Riesman’s footage before I ever read his name. He, alongside others, captured something on camera which provided significant fuel for conspiracy theorists’ narratives about the collapses.

About 15 minutes into Riesman’s tape, the first collapse (of WTC2, the South tower) is imminent. He doesn’t know this of course, but made a fortuitous decision.

“I zoomed into this particular part of the building where the craziest stuff was happening,” he says. “There were sparks coming out, I could see there was bent metal and I was like, ‘This looks really interesting, I’m going to zoom in there’. And then, of course that’s exactly where the building buckled.”

The ‘sparks’ coming out were interpreted by some as ‘molten steel’. Some readers may be familiar with the ‘jet fuel doesn’t melt steel beams’ meme; it comes in part from the way Riesman’s footage was interpreted and utilised by conspiracy theorists to posit that the interiors of the buildings were otherwise interfered with, in order to encourage – or actually cause – their collapse.

It’s a good thing Riesman made that creative decision. The close-up detail of the ‘sparks/molten substance’ and the process leading up to the building buckling have been useful for the National Institute of Standards and Technology, whose major study on the causes of the Twin Tower collapses crowdsourced more than 14,000 videos and images from the public to map the spread of fire and structural failure.

Was that initial experience, watching the unexpected collapse up close, traumatic for him? “If I had seen up close the human life that was lost, I think it would have been,” he says. “I saw the building fall down, so technically I saw a lot of people die, but, if I’d seen one actual person up close, it would have disturbed me. I was just shocked.”

It’s clear that for all three, the subsequent political upheaval – not least the recent mess in Afghanistan – was as significant as 9/11 itself. Tami was told by a Vietnam vet who phoned into her radio show that she needed to “deal with her PTSD before it dealt with her”. One way she did this was by participating in the prosecution of Zacarias Moussaoui, the only man so far convicted for involvement in the 9/11 plot.

Much of our conversation revolved around her work since, including her involvement in bringing al-Qaeda members to justice and working with the FBI as a witness. She’s deeply frustrated that President Biden plans to close GITMO because she believes closing the facility will mean the men held there, including self-proclaimed ‘9/11 mastermind’ Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, will never face justice. When she brings up ‘the people who jumped’, it highlights not only the depth of the terror and emotion that drives her formidable presence, but also the crystal clarity with which she remembers the worst of the event.

“There was one man, who I focused on,” she recalls. “I thought, ‘Somewhere this man has a family, friends, parents. And right now this man is alone’.”

As she watched him forced off the building, though not a religious person, she prayed for him and, in her words, “stayed with him” as he fell.“I thought to myself, ‘You’re not going to die alone, I’m right here with you.’”

She later watched three people jump together, two men who put their hands on a woman’s shoulders, while she held her skirt down. “How incredibly human," she says.

All three will observe the anniversary this year. I ask Mark LaGanga how often he has revisited his footage, whether it’s easier now. “It’s very dramatic – the sounds, the sirens – I didn’t know this at the time but those sirens you can hear coming from the dust are downed firefighters. I’ve watched it very rarely; I made a point not to.”

As every year, Tami Michaels and her husband will have dinner with their family, their way of celebrating life together and quietly acknowledging the couple’s experience. Ben Riesman has been contacted by a number of documentary makers, who will use his footage in anniversary pieces. He will also show his raw footage in public for the first time, as part of a local arts festival.

“To see it in person on a big screen with a sound system might be really interesting,” he says. I’’m interested to see how that feels. It doesn’t feel wonderful, but it feels like I have an interesting perspective on this huge crazy historical moment.”