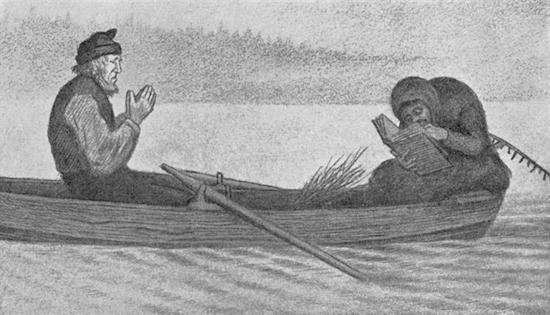

Over Sjoe Og Elv by Theodor Severin Kittelsen

On the pristine train to Oslo a big man in a Dimmu Borgir shirt whose light blue medical mask is so big he is nearly wearing it over his eyes. He reaches into his black backpack covered in patches (Mayhem, Darkthrone, Slayer) and gets a small and round silver box out. The metalhead takes the mask off, carefully opens the package, moves his fingers into the direction of his head, opens his mouth, puts some snus between his cheek and purple gums, starts chewing before placing the mask back where it belongs.

Welcome to Norway. The country where there’s always something primitive and dangerous hidden under a clean and seemingly safe surface. Norwegians Ibsen and Grieg created works that with resound with this very concept and now reside in the nation’s artistic canon. They have built a national identity. And contemporary artists are still developing a sense of Nordic pride. Its experimental scenes — including black metal, free jazz, noise — are definitely worth traveling for. Because nowadays live performances by sonic explorers are as rare as toilet paper was during the first days of the pandemic.

I will be the first international visitor in 18 months to Blå, one of the leading contemporary venues for everything leftfield in all musical genres. Their Vrompeis Fest 2021 is a perfect example; it features shows from contemporary composers like Maja Ratkje, noise-rock bands such as Deathcrush and guitar masters like James Welburn. Even the acclaimed Norwegian author Bård Torgersen is on the poster.

Also new discoveries can be made, like the extraterrestrial world music of Alwanzatar, an alias of Kristoffer Momrak, member of prog-rock outfit Tusmørke. Maybe the first artist ever to wear rubber boots on stage, and looking like a long-haired history teacher (which he actually is), the cosmic composer is inventing new levels of weirdness, inventing the prog rock side of Aphex Twin. It sounds like acid on mushrooms from a Norwegian forest; intelligent dance music for elves. Momrak is using instruments that attract cliché in general (flute, theremin), genres that are clichéd (prog-rock, IDM) but still pushing the perspective forward once more. Maybe, from a retrospective perspective, Aphex Twin was the prog rock of the 90s. Alwanzatar would not only fit in at forward-thinking metal festivals such as Roadburn but would also rock a massive acid party like Bang Face Weekender.

Another highlight of Vriompeis was Sheriffs Of Nothingness; something completely different. Two seriously looking string players, one of them persistently wearing a medical mask, take the stage. During an acoustic set full of popping and snapping noises, the duo reflects on their situation: “Tonight is the release party of our last album. We released it in the fall of last year.” Sheriffs Of Nothingness consists of Ole-Henrik Moe on viola and Kari Rønnekleiv on violin. They are two of Norway’s most distinguished artists. Both received the Norwegian Grammy. Moe played on records by Motorpsycho, Deathprod, Jenny Hval and many more.

And now it’s the last day of July. Almost a year later. Their album An Autumn Night At The Crooked Forest, Four Fireplaces (In Reality Only One) is dedicated to the hearth, maybe one of the most traditional places for people to come together and share experiences. A place where nature is comforting and dangerous at the same time. A place where you just can be and surrender to the void.

Their first composition consists of a Tony Conrad-like drone which sounds like a mosquito on a hot summer night. Beautiful and uncomfortable at the same time. It’s a meditation on the timbre of their wooden instruments. Technically very difficult, played by a duo that’s a perfect match. But I’m bored. If it were a CD, there would be a forward button. If it were a real mosquito, I would swat it. Now I’m forced to listen and think about things.

The album was recorded in October 2019 in the middle of Krokskogen, an old forested area west of Oslo, in an old cabin, and by a fireplace that was, in different ways, burning all the time. By listening carefully you may hear the fire, crackling gently. Compositions have names like ‘Muted Birch-Logs’ and ‘Great Spruce-Log’. Because of Covid regulations it was not possible to have the audience sitting around them, which Sheriffs Of Nothingness originally intended. So they perform on the stage.

A fireplace is like a concert. Although Norwegian public TV broadcasts a 12-hour wood-burning programme, there’s nothing compared to the real thing. Fire is the reason this country exists, otherwise everyone would freeze to death in winter.

Like campfires don’t really burn on TVs and words don’t live in books, music does not live on records. The first vinyl recording was made to replicate the live concert. Fundamentally, music is a shared experience. Although music is only air moving around, it’s not a matter of sound being transported from amplifier to eardrum, between artist and audience. Music is a liberating trip where you can become free of yourself. Where bodies touch each other without touching. When emotions flow, memories are being created. By listening, we translate our inner feelings and emotions toward outward movement, trying to disappear in the audience. The body of an audience starts to move to the flow.

Live music is all about tuning. Blå is an old graffiti-covered factory mutated into a music venue. Outside, on a beautiful terrace next to a river, beautiful people are partying and drinking beers with a Viking mentality. Boof, boof, boof, a DJ is playing. Bang, bang, bang, toilet doors are opening and closing. Inside, the PA zooms and buzzes, angry at the musicians for not being used when it’s finally possible again. Grrr… Grrr… Grrr… Those bastards! All the life on the terrace outside blends with the acoustic ambience inside. A purist would prefer a soundproof concert hall with state-of-the-art acoustics. But this is an experience of real listening. If you want to hear the naked sounds you can play the CD at home. This setting leads to new dynamics and new forms of sonic awareness. We are the outsiders sitting inside.

The always fun and flexible Blå booker Sten Ove Toft started the concert series Klubb Vriompeis in 2007, bringing sonic arsonists like Justice Yeldham and Stephen O’Malley to Oslo. For 2021 it pivoted to a festival focusing on the experimental Norwegian scenes. Vriompeis is an old saying, slang for a person being or acting difficult. A stubborn person. Toft put himself on the bill as an opening act: he is performing under the moniker Undertegnede with country singer and producer of the upcoming Darkthrone album Silje Huleboer. It’s country noise with the voice of an angel, covering ‘Anytime You Need A Friend’ by Mariah Carey. Both are putting loops and drones to it. They set the tone for the rest of the three days: absolute beauty, combined with freaky sounds in all kinds of genres and styles.

Before the concert, Toft, wearing a black T-shirt, drinking black coffee and smoking Camel Blue, was fighting with Facebook to announce a three-day residency of Supersilent while doing an interview. “I’ve been on furlough for 14 months,” he says, “so it’s amazing to create work for artists, staff, the administration and myself.” The Norwegian Arts Council announced the last stage of the "Covid Stimulation Package" ten days prior to the application deadline of the 1st of June. The total budget for the last period from July till October was around €75 million — quite an investment for a country with 5.5 million inhabitants.

There was quite the stir last year when World Idol winner Kurt Nilsen got 13,300,000 kroners (€1,271,000) for 26 Christmas concerts that they already knew would be cancelled. But in general the money seems to be well spent. It went to the whole cultural infrastructure, from bookshops, booking agencies, film distribution companies and festivals like Inferno and Øya, to stand-up comedians and artists like Paal Nilssen-Love and Kings Of Convenience. I’m asking Toft if Turbonegro also applied: “A lot of the major bands haven’t dared,” he says. Some have even blatantly said “give it to those who need it, we’re good”. That’s Norway at its finest.

In under a fortnight Toft booked 230 events for Blå for the period between the start of July and Halloween. Which might be a world record. They were funded to the tune of 15.4 million kroners, approximately €1.47 million. Even with the restrictions of a maximum of 40 people in the audience, this allows them to operate with a normal production and create jobs they would normally not be able to do with the restrictions.

Toft looks at the action around him and proudly says: “This gets the wheel spinning and gets people back to work instead of having all of them on furlough”.

I’ve travelled from the deep-red Netherlands to green Norway. There was uncertainty at the border. Fully vaccinated people from Africa and Canada were sent back. After Customs scanned my QR-code to check if I’m fully vaccinated, they gave me a photocopied paper so I could skip the Covid tests. These things could be forged very easily by using a copy machine. Norway is not used to foreign visitors yet. Venues only accept payments with QR-code that only works with a Norwegian bank account. Cash is considered dirty.

After being stuck at home for 18 months, this trip feels dangerously new. A stranger sitting next to me. Eavesdropping conversations. The sound of crying babies in an airplane. The smell of puking babies in an airplane. The sound of drunk people in the street. The sound of drunk people puking in the street. And of course there’s the excitement of artists pushing boundaries of noise volumes, bass in your face, smoke machines, flashing stage lights, a live audience of like-minded people, conversations about music, more music, øl, jokes, the smell of cigarettes, falling beer glasses, more øl, real-life discussions, tasting the bitterest ever bitter, being bored, being excited; the feeling of collective effervescence, a sense of belonging and real meaning produced by collective action.

Quietus favourite James Welburn played a great concert where he pumped up everything that he normally plays calmly and smoothly. These were drones on steroids. One month he had been working on a special solo set in a soundproof cabin somewhere close to Lillehammer. For the performance itself Welburn was almost invisible, covered in blue light. The only striking thing was the very long neck of his guitar. The result sounded like Sunn 2.O))) with guitar riffs on a very high level, stripped to the bare minimum, almost making them mechanical. The audience could feel the tension and the release of performing again. At the same time there was the ambivalence of listening to loud guitar music I can feel in my stomach while sitting on a bar stool, unable to move to the heaviness of the sound, without a headbanging audience of people standing next to me, it still felt abstract and unreal. It was just there, a big ocean of riffs, full of sounds to get lost in, firing the senses to overload.

Talk about sensory overload: already, the first 30 seconds of Deathcrush on the first day was everything we have all heavily missed during lockdown. Their physical and shamanistic approach to live shows opens up a spiritual side in the audience. They’ve broken with the song structure of their former punk-noise work, broken up with a band member and operate as a duo consisting of the ferocious and energetic singer/performer/guitar player Linn Nystadnes and drummer/electronic guy Vidar Evensen, the coolest couple in town. The new set is only about texture, tension and release, moving their sound more from the noise rock of Sonic Youth into the legacy of surrealist post-punkers Chrome; with whiffs of Suicide. Deathcrush proves that they are still one of the most exciting live bands. Always pushing things forward.

After the concert Evensen, in perfectly coutured thrift shop clothes, is feeling both release and exhaustion. After months of composing and rehearsing, Deathcrush could suddenly perform. They released their record in March 2020, planned a tour with a release party in Oslo and a few weeks touring Europe. “On the release day Norway got shut down”, he tells me. “That’s a proper flop, you might say.” It was Friday the 13th. “So finally it happened”, he continues. “Once in a lifetime actually.” The music press was only talking about the pandemic. Getting reviews was hard. “You lose attention”, Evensen says as he moves his eyes to the table. “But it sold OK.”

Deathcrush was on the brink of losing all their savings, which they had put into the tour. But then the Norwegian cultural department stepped in. “We are very privileged compared to other countries”, Evensen says. “We could keep the funding for the European tour and got a grant for programming and composing the new album. Still, making music was weird. It was hard to get inspiration while not going to gigs. The chit-chat is gone. It’s all about the medium itself. My lyrics are more references to books, rather than real life experiences.”

How is it, being a revolutionary in a welfare state? “It’s very easy”, he says decidedly. “Because you can rebel against luxury and ideas and philosophy. You don’t have to struggle with real world problems. It’s more of an intellectual rebellion.” For people from other countries, working as an independent artist, wearing a nose piercing, rehearsing in a former squat, coming from a culture of resistance but being dependent on the state might seem contradictory. Especially when you’re working in the field of pop music. Evensen can’t agree with that: “Norway is a special case. We’re just a small country with a low population. Without funding, some things we really like in society would not be possible. I don’t own a car. I only use the road when I’m touring. But I still pay my taxes for building roads. The cultural part is what my life is about. It’s a fair share.”

In July Norway got cultural life on the road again incredibly quickly. Next to government funding, a fundamental DIY approach is key to the Norwegian scene. A flexibility of roles is the default mindset. Evensen plays in Deathcrush but also takes care of visiting artists at Blå, books the rock venue Revolver in Oslo and keeps expanding his scope. During the pandemic he took online marketing courses: “I’m learning all the tricks evil, to use it for good causes”, he says with a twinkle in his eyes. “I finally have the time to do other reading than just weird books.” It’s not something only for his own projects. The knowledge flows back: “I’ve already spoken to venues and record labels,” he says. Labels and bands want him to work for them so he can tour and at the same time help the music scene at home.

This small scale and hybrid approach seems very healthy. Lots of artists perform solo or as a duo. On the bill at Vriompeis there are no big bands that need to rehearse and book a tour, just Norwegians With Attitude. Often in new combinations. Trying things. In their approach improvising is composing. Evensenen comes from the small town of Haugesund. “A lot of people moved to Oslo to be able to do live stuff,” he says, taking a drag from his cigarette. “In a small place you have to develop everything yourself from the bottom up. You’re really cut off. There’s no good record stores. There’s no equipment shops. Creative people, freaks and the drug scene all connect. They are the only alternative people. It’s good and bad. Some get fucked up and lose their talent. Some thrive on it. I’m friends with crust-punks, drug addicts, maniacs getting in and out of hospital, but also people who work in the government. That’s the game of a small place. It’s more of a balancing act, or a balancing game.”

On day two, the internationally acclaimed composer Maja Ratkje is headlining with a noise show. It’s still 40 people sitting on barstools. A person in the audience is doing fist-pumps, moving his closed hand up and down several times as a sign of victory. Nothing wrong with a good dose of Viking dancing. Earlier, people were air drumming from their chairs. But the context is quite peculiar: is there any other country where the top contemporary composer plays a noise show in a former squat for 40 people, including a lone fist-pumper sitting on sports bar furniture?

Maja Ratkje is unparalleled. She composes for distinguished orchestras, works in the jazz field, and also knows her underground noise. With this set she shows that, to her, those totally different fields are not separate entities. Calling it noise is too easy. Calling it improv is too easy. Combining extraordinary craftsmanship on both electronics and voice, she shows what a great musician she is. There’s always a sense of structure, of composition, but not within the traditional forms. Ratkje challenges her listeners and knows exactly where she’s taking them.

At first it sounds like a Pierre Henry remix of Tom Tom Club, with gliding and sliding noises reworking the voices of female rappers. At the end of the set the listener is transported to totally new territories. Ratkje puts a piece of styrofoam between her microphone and throat. Then, with her own voice, altered with electronics, she produces a primal scream that’s so intense, so scary, so real. It makes Coil’s Hellraiser soundtrack, or Suicide’s ‘Frankie Teardrop’ — considered by some to be the scariest music ever being made — sound like easy listening.

Nordic culture has a long history of screaming. Of course there are the screams of Munch, the sax sound in free jazz, and the typical screams and growls of black metal. It all goes back to Galdr, an old word for “magic spell,” which is a falsetto-like primal scream. Some are used for magic healing.

Ratkje’s voice is unforgettable. Her performance is unforgettable. 18 months of fear of death, of isolation, have been squeezed out by one throat. My memories about this period will not be about doomscrolling and home shopping. This scream. At that transformative moment. From a real voice. From a real PA. With real people. With real emotions. That’s what life is about.

Fear and death seem to be an integral part of Norwegian culture. There’s a vivid tradition of Black Death legends like the old Norwegian tale about Pesta, a pallid old woman who travels the country with a rake and a broom. She’s the personification of the Plague. If she carries a rake, there will be some survivors; the broom means no one will escape. And if she carries both, the outcome is uncertain. The tale embodies the stereotypical Norwegian wariness of new influences. But at the same time they are a country of traders: although the outside world is scary they’ll have to deal with it and sail the seas of global commerce.

The traditional Sami songs are a big part of the Nordic heritage. Yoiks, notable for their static drones and bass lines, have a special influence on contemporary music. There’s a long line, from Grieg to Gabarek to Wardruna to Lasse Marhaug, all transforming tradition into modernity in their own way. It’s a combination of cultural and esoteric rituals; modernist strategies mixed with a primitive past.

Filip Roshauw is one of the festival’s visitors. He works at the Oslo World festival, played with avant-garde metal band Virus and writes for Now’s The Time, a weekly blog about the Oslo scene for the jazz magazine Jazznyt. He’s reflecting on the extremes: “Fenriz from Darkthrone, one of the biggest black metal artists ever, works at a post office”, he says while sipping a beer. “Fenriz enjoys the quiet life, watching Kolbotn, the local women’s football team — and the biathlon. He enjoys the calm. I hear these calm movements in the music”, he says. “Black metal is slow and romantic. It has a lot to do with the jazz label ECM. You could do a sampler with half Jan Gabarek and the other half Burzum. It would make total sense.”

But still — Accusing the notorious murderer, church-burner and all-round dubious Varg Vikernes of making elevator music, that’s something radical. “There is a lot of noise in his music,” Roshauw explains, “but a lot also has a softer side to it, without compromising.” According to Roshauw the Norwegian free jazz scene has the same characteristics: “It’s jazz with a smile. Ordinary life is so noisy. You have to create a different space. Noise is a valid protest when society is too silent. Where do you go when politics is bizarre and grotesque? It might be dirty and mild, messy and kind.”

Norwegians take their pride in extremes. “Even people who don’t listen to it say: ‘we’re good at that’”, Roshauw says. “Politicians brag about black metal in Norway. Which says a lot about social-democratic cultural policy. It starts as underground, outcast, contra-everything and it ends up being something we’re really proud of as a national culture and also city-wise.” At Neseblod, the infamous basement where black metal started, there’s even a guest book for the blackpackers – international tourists on a black metal pilgrimage. “Molde and Kongsberg are small cities, the jazz festivals started as something the city was sceptical to”, Roshauw says. “But now it’s a point of pride. Jazz and the festivals are very important for Norwegian identity.”

And that identity is everywhere. When I open my hotel window on a Sunday morning I hear a trad jazz band playing on a public square. Along with a colleague, Roshauw started Now’s The Time because the activity in the Oslo scene had been so high the previous couple of years. “I thought: what’s gonna stop this?”, he says, then taking a sip of his beer. “When does the bubble burst? And then March last year came. I feared for the small alternative stuff. But what the period showed was that when there was a possibility of having some kind of concerts the alternative scenes were best equipped.” Places like Kafé Hærverk and Blå were quick to reactivate and Roshauw is proud of that: “The situation has proved that this is a quite special moment in Norwegian alternative music. It also says a lot about the social security net that music has in Norway.” The jazz world receives some money from Norsk Jazzforum, a collaboration between musicians, jazz clubs, bookers, festivals, the whole scene. “The collaboration is more important than the money in itself”, Roshauw says. “When the pandemic happened at least some money was close at hand, which could be distributed by people with knowledge of the scene and where it was needed.”

The last day. The last act. I thought I’d already heard everything experimental, but the acclaimed writer Bård Torgersen will be performing with the saxophonist and violist Dario Fariello, who comes from the improv scene. I thought about dropping out, because I don’t like literature as performance art. Poetry is a solitary act. Besides, the Norwegian language is a bridge too far and there will be no subtitles tonight for the first foreign visitor in 18 months. Sten Ove Toft is trying to get me the translation, but Torgensen quickly messages him back that it’s impossible. Their whole performance will be improvised.

Before their performance Torgersen, a writer who looks like the cool uncle that might give you Metal Box by Public Image Ltd. for your 13th birthday, assures me that understanding is not an essential part of language: “I’m working with Dario, who is from Italy”, he says. “We speak different languages and meet in the middle.”

I ask him whether there’s any difference between working as a writer, which will always be an introverted job, and working as a stage performer. “To me it’s been very helpful to do live performances”, he replies. “You move in different characters, in different moods. And always become a different character. When I write it’s helpful to also do the performance bit. I can take the solitary experience of writing onto the stage. I like this cross-pollination between literature and performance.”

He’s right. And the result is hard to describe. Torgersen (silver hair, big beard) is a true performer who has been on stages for decades. A Blixa Bargeld without the pretentious abracadabra and blablabla. Togensen and Fariello are confronting the audience with their feelings of shame and Unbehagen. It’s a dead serious game about meaning, semantics, rehearsing and playing. Two improvising artists playing with all the clichés that improvisers can do. Deconstructing the meaning of performance with a lot of fuel for loud laughs. And also some seriously disturbing poetry as well. One poem is especially touching:

The future of language. The future of the book. The future of the poem. The light at the end of the tunnel. The other tunnel. In the end of the language. Another tunnel. And a tower. Big big big big big big big big big big big — tower, tower tower. And a tunnel underneath the tower. And a light. A new tunnel. The future of the tunnel. A light at the end of the poem. This is too direct maybe? Can you hear me? Can you hear me? Can you see me? Is it OK? Is it OK? The future. Tunnels. Towers. Light-speed. Big big big big big big big big. After. The start.

Talk about a new start. Will the pandemic lead to different arts? In pre-Covid times dystopian fiction about fear was en vogue; Torgersen wrote about societal breakdown in his debut novel Alt skal vekk from the year 2005 and has returned to it many times as a topic: “Hope and fragility are totally different emotions. I’m interested in how things can collapse. After it happened I wanted to move away from it. It’s been true that it could happen. What can come after this? What can be built from this?” he says to me. “It’s more interesting to reach out to new possibilities. How can we get out of this, while remaining relational, being kind and open, getting through this together.”

I push the stop button. This is a great ending. I’ve travelled to Norway to feel and hear how a unique musical scene can still develop. It’s what Iggy Pop says: it’s about a lust for life. Although death will always win, we can learn from ancient stories that still channel our primal fears, and build something human and optimistic from despair and deception. All by ourselves. I’m contemplating Maja Ratkje’s primal scream, the sonic meditation at the musical campfire of Sheriffs Of Nothingness. Who will envision a story about a new Pesta that will be told by generation after generation?

Three days of festival and constant social contact have exhausted me. Irrationality is starting to set in.

I want to leave and give Torgersen a big hug. But suddenly the poet-performer continues talking and I push the record button again. Now I’m listening back to it, at home. It’s so beautifully said, maybe even comparable to that time Werner Herzog Went to the jungle and was overwhelmed by misery, one of my favourite views on nature ever. So I wanted to keep everything like a closing aria. And share it with you.

“We need to rethink our relationship to death”, Torgersen says without hesitation. “We’ve been living for a long time avoiding risk. If the pandemic continues we’ll have to live with the virus. The need to be with other people is stronger than the fear of death.” Torgensen comes a bit closer, and continues: “We’ve been told all the time that it’s irrational: when you live here, especially in winter, it’s quite rough. It’s cold. The environment tells you it’s impossible to be here. But at the same time it’s a very safe, controlled, easy society”, he says with the ease of a writer who’s totally into it. “You have to live with the paradox. You can be drawn into different directions. If you walk out in the winter and stay there you’ll die after 12 hours. It’s dark — dark and cold”, he says to the recorder. “The country is manic-depressive. Wintertime is so down. No smell. No colour. In the summer it’s totally the opposite: there’s no darkness. There are smells and colours. You have different moods.”

Torgersen is guiding me through emotional landscapes: “You have been told all your life that safety is important but people have an undercurrent of rebellion against that. I like that everything can break down, I like the risk”, he says to the recorder. “The fragility. The world is in a fragile state. Use it for something. Be in touch with it. It can be overwhelming but still it’s interesting and valuable to feel the fragility without being scared of it. But also without the opposite, like pushing it away and being cynical.”

Torgersen takes a small break. “We have been living in times where everything went bigger with more and more people, everything’s working, working, working, not thinking about how fragile things really are.” And he’s trying to finish it. “Now we have been confronted with a more true reality. Which is fragile. This is more real.”

For real.