Shirley Collins’ late life renaissance is one of the most heartening stories of the past few years. Since she returned, triumphant, in 2016 with her first album for forty years, Collins has enjoyed the acclaim of an audience delighted by her reignited cultural role. Her follow-up, Heart’s Ease, provided balm when it was needed most last year. Now, at the age of eighty-six, she releases Crowlink, a collaborative EP which contains the most experimental work she has ever recorded. Embedded deep in her homeland, the South Downs chalk, the music seems to emanate from the land itself in a powerful affirmation of identity and place. Crowlink, high on the South Downs above the Seven Sisters, is Shirley’s favourite place “to sit and think about what’s gone, and what is to come”. It is where separation between realities has worn thin.

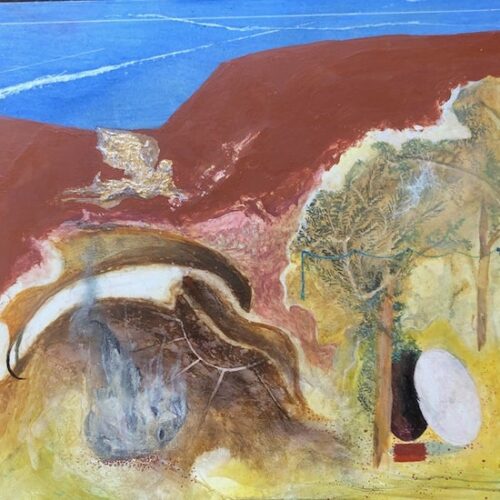

The cover of Crowlink is a remarkable, Paul Nash-like painting by Brian Catling. It reveals the landscape to which the music belongs, and signposts the calibre of artists of the hidden realm for whom Collins now provides a fulcrum. The EP is produced by another, Matthew Shaw, who takes the final, least traditional track on Heart’s Ease, ‘Crowlink’, as the jumping off point for stranger territory. The record begins with Collins speaking lyrics from ‘Just as the Tide Was Flowing’ as though describing recent events, then an instrumental track, ‘At Break of Day’, performed by Shaw with field recordings from Crowlink itself and Vaughan Williams strings. Three songs follow, one of which is a new version of the eerie Sacred Harp song ‘Wondrous Love’, included on Heart’s Ease but now retitled ‘Through All Eternity’ and made even eerier. ‘Sailor Boy’ is an echoing track, washed with sea sounds and longing. ‘The Rose and the Briar’ is the Child Ballad ‘Barbara Allen’, another song of deep longing, with hurdy gurdy played by Ossian Brown (Coil, Cyclobe).

On the surface Collins has returned to her beginnings as a folk singer, something denied to her for much of her life, but she is now a very different singer from her younger incarnation. When she was travelling with Alan Lomax in the Appalachia and American South during 1959 collecting songs, she was the outsider bringing an anthropologist’s eye to other cultures. Now, she is the culture. She has become the singer she searched for in her youth, someone soaked in the song of the place they belong to. We rarely hear the singing voices of older people on professional recordings, and Collins’ voice is now reminiscent of field recordings made by early folk music collectors in pubs and farmhouses – people singing the songs they knew, the way they sang them. Separated from the folk revival and the music industry of the 60s and 70s that made her name, Collins is unique, free, and singing the best songs of her life. She has become the thing she worked to preserve – the messenger, giving music new meaning for new singers.