A Coil publicity shot, circa Love’s Secret Domain

Coil’s Love’s Secret Domain is perhaps the band’s most potent time machine, albeit one locked firmly to the spacetime coordinates of its creation, 30 years ago. And, while it certainly reflects the musical world that it emerged from, on reappraisal it’s also clear just how thoroughly othered its influences were by exposure to Coil, and how unique its collision of, amongst many other things, noise, acid house, flamenco and musique concrete still sounds.

Its title track’s howling torch song groove, the crackling electro-exotica of ‘Teenage Lightning’ and the jarring excesses of ‘Things Happen’ remain unlike anything else I can think of, while ‘Titan Arch’, ‘Chaostrophe’ and ‘Dark River’ sound like, well, classic Coil. Even ‘The Snow’, with its hefty kicks and snares marking Coil’s deepest nod to the period’s all-consuming club culture, now feels more weightless and aethereal than it does corporeal, while the throbbing bass undertow of the album’s glistening, hypnotic centrepiece, ‘Windowpane’, should have made it an eternal club anthem.

Sure, there are occasional missteps – the foregrounded didgeridoo on ‘Where Even The Darkness Is Something To See’ was perhaps an unfortunate choice – a crusty scene cliche even at the time, now further tainted here in the UK by the shadow of Rolf Harris; and the rhythmic backbone of ‘Further Back And Faster’, a sample from Renegade Soundwave’s ‘On TV’ chains it firmly to its time, even as the Performance and Night Of The Hunter vocal snatches pull it into other dimensions (and thankfully the didge has by now been significantly mutated). But the combined musical impact of Love’s Secret Domain remains undiminished: a sonic world erupting with mind-spinning ingenuity, that beneath its surface strangeness, holds more hooks and grooves than a Cenobite’s playroom.

As always with Coil, however, Love’s Secret Domain is about more than music; it’s an exploration of what it meant, in 1991, to be a deeply inquisitive consciousness, all channels on, all bandwidths open, trapped in a human body and surrounded by the joy, anger and madness of existence. It’s a palimpsest of an incredibly potent time for London’s underground cultures, a mindmap of spaces, now largely lost, that I was discovering for myself as a teen: from music shops – Ambient Soho and Sister Ray on Berwick St in Soho, Vinyl Experience in Camden, with the motorcycle permanently crashed through its window, Rough Trade off Covent Garden, and on Talbot Rd in Notting Hill, around the corner from the Powys Square house where Performance was shot, and where, for many years, a Coil poster of a teenaged boy with electrodes running into his Y fronts hung threateningly above the counter (Teenage Lightning indeed); bookshops: Compendium in Camden, for all your beat and counterculture needs, Atlantis, Skoob and Watkins in Holborn for the occultists, So High Soho for psychedelia, Forbidden Planet 2 for genre films, books and ephemera and the Fantasy Centre on Holloway Rd for pulp SF, fantasy and horror; indie cinemas like The Scala in Kings Cross and The Metro on Rupert St; live music venues, Subterania on Ladbroke Grove, the Mean Fiddler in Harslden, the George Robey in Finsbury Park; club nights like Club Dog, Rage and Megatripolis at Heaven, Hardclub at Gossips on Dean St, and queer worlds, unknown to me at the time, like Trade and FIST. These were the some of the physical and psychic spaces we travelled to, and through, to feed our heads.

That Peter ‘Sleazy’ Christopherson and John Balance (Geff Rushton), Coil’s body and soul, are no longer with us is one of the culture’s tremendous losses, but they persist through their works, inevitably, and deservedly, more widely loved and appreciated now than ever in their lifetimes.

Thankfully, however, we can still talk to Stephen Thrower, Coil’s core third member during its first phase; now of Cyclobe and UnicaZürn and a much admired film historian. So please join us as we roll back the hands of time and re-enter Love’s Secret Domain…

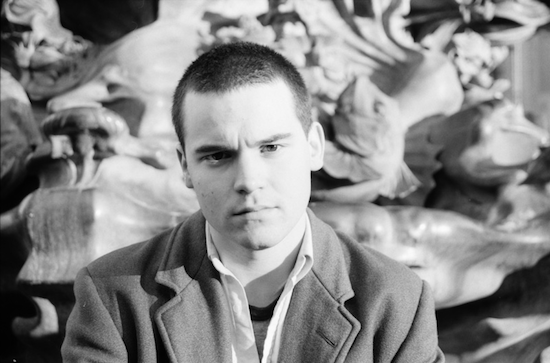

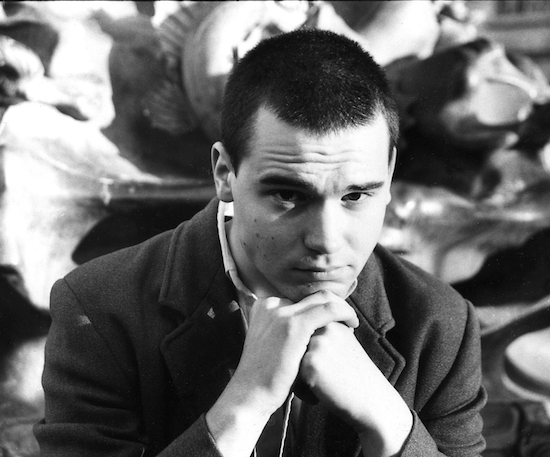

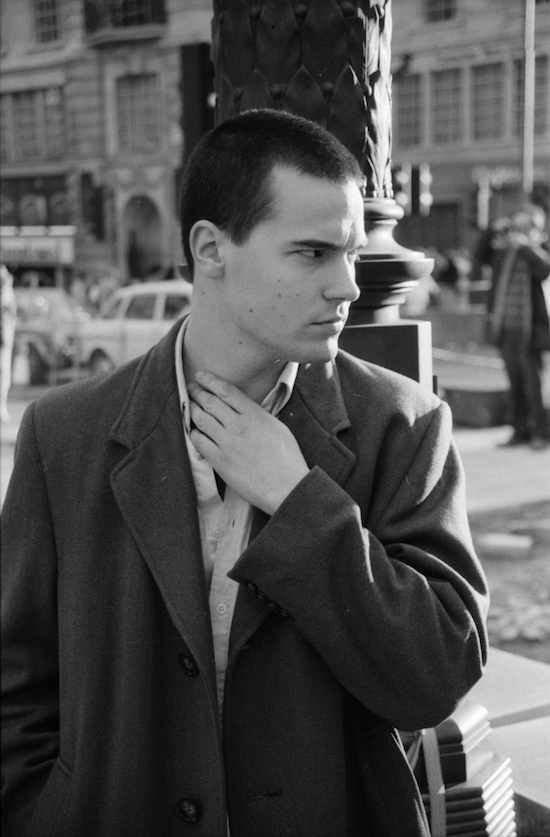

Stephen Thrower, portrait by Peter Christopherson, late 80s

How did you first get involved with Coil?

Stephen Thrower: I first got in touch with Sleazy in December 1983, when he was still in Psychic TV. I wrote a letter saying how brilliant I thought their video for ‘Terminus’ was, which he directed. We corresponded frequently after that, during the time that he and Geff left PTV and pooled their resources as Coil h. In August 1984 they invited me down to London, and we got on so well that a month later we were in the studio in Chalk Farm, working on the Scatology sessions. I co-wrote two tracks, ‘At the Heart of It All’ and ‘Solar Lodge’, and played on three others (‘Clap’, ‘The Spoiler’ and ‘Godhead-Deathhead’). Things moved pretty quickly after that, and I moved down to London permanently in summer 85.

Was Coil something that was always happening for you, or was it only when you were with Geff and Sleazy?

ST: In the musical sense, it was something that happened when I was with them, and principally when we were in the studio, but we were listening to music all the time together and they were among my closest friends. So really it was a friendship, especially with Geff, because Sleazy would be away frequently, globe-trotting and shooting commercials and music videos.

Geff and I would just hang out, listen to records and get blasted in one way or another. We had a shared love of absurdity and playfulness. something we both were always concerned should be present in Coil, because the one thing we didn’t want it to be was some sort of gloomy goth cliche. So that humorous side, the antic, sort of absurdist side of it was something that we bonded over, and was part of our shared enjoyment of each other’s company. Having said that, ‘At the Heart of It All’ is probably the most sombre depressive piece on the album, so musically I was tapping into something darker too.

Another important facet of the way that we were with each other was that we both enjoyed delirium, and obviously chemicals played a significant part in that. There was always a strong element of intellectual curiosity, plus hedonism, which led to a fascination for delirious and out-of-control states. But it was really about the enjoyment and fascination of it, rather than just a kind of dry experiment.

Musically we might play around with instruments and record ideas down as improvisations, but that didn’t take up a lot of time. It wasn’t like when you hear accounts of Can recording constantly for weeks on end. It was more that the ethos and the attitude and the shared sensibility was kept alive via the friendship, and then when it came to the recording sessions, the dam would burst and out would come, you know, the musical expression of that.

Sleazy would hire in expensive new equipment like the Fairlight sampler or the Emu Emulator, and would often be up all night making samples, rhythm loops, and audio peculiarities – this was something he would do to amuse himself, as much as anything else, and he built up a fairly extensive library of sound ideas like that. Geff would contribute to some of them as well, though I wasn’t always aware of quite what he did – he wasn’t a programmer or tech savvy in the same way that Sleazy was – but I think he probably did have some interaction with them.

Sometimes the three of us would sit together and play melodic ideas, but at that stage it was mostly just a matter of listening to and selecting these often quite rudimentary, basic sketches. With Scatology, a lot of the basic home-recorded ideas were little more than rhythmic loops, though they got more complex as home studio technology started improving and Sleazy was in a position to do more before going into an actual studio.

While we were listening to things I would suggest adding elements, but my direct musical involvement was almost always later, in the studio, playing live instruments. Geff and Sleazy lived in a very nice three-story semi-detached house with neighbours on one side, so we didn’t want to create too much cacophony. I played saxophone, guitar and kettle drums, things you can’t really play quietly! Well good players can play quietly, but not me!

How did the tracks themselves evolve?

ST: It varied. The first two albums happened relatively quickly. I think the initial recording for Scatology might have been six months before the proper studio sessions, and the same with Horse Rotorvator before going into the studio two or three times. Gold Is The Metal With The Broadest Shoulders was an album of material that didn’t make it onto Horse Rotorvator, but which we still thought was good, so we made our version of The Faust Tapes – a collage album.

Those came out in 1985, 86 and 87, then there was a bit of a gap until Love’s Secret Domain came out in 91, because there was an attempt to do another album in between, which never came about – The Dark Age Of Love. Ideas were being put together, but at some point Geff lost affection for it. Some of that material ended up being rejigged and refitted for Love’s Secret Domain.

Our non-Coil lives were also starting to interrupt the music. I started writing for Shock Xpress around this time [a vital horror and trash film zine, edited by Stefan Jaworzyn, also a great source for wild music coverage] and began my own zine, Eyeball in 89.

I think there was possibly too much going on… socially… as well. Maybe the club-life side of Geff and Sleaze was slightly cutting into getting an album done!

Stephen Thrower, portrait by Peter Christopherson, late 80s

Love’s Secret Domain features a varied roster of guest artists. How did they get involved?

ST: Marc Almond had been a friend of Geff and Sleazy’s since Psychic TV and was always up for doing something. Annie Anxiety had been living in London since the early 80s. She’d met Sleazy back in Throbbing Gristle days, and Geff and I were fans of her work with On-U Sound.

Contacting Charles Hayward was my suggestion. We were talking about the limitations of sampled drums and drum programming, and the benefits of a live drummer. I was, and still am, a huge fan of This Heat and thought that Charles would bring a really interesting new development to the sound. I knew that he was massively gifted as a player, and thought he and Coil would be an interesting combination. Geff liked Deceit as well, so it was an easy thing to agree about.

Mike McEvoy, who played the keyboard solo on ‘The Snow’ was recording in the next door studio. We were working on the song and everybody was on E – although I’m not sure if he was – but he sort of floated in, in a very lovely way, and said, “Hey, this is great! I’m just working in the next studio and I heard this coming together and thought I’d come and say how much I liked it.” In the general, euphoric, improvisational spirit of the session he was invited to just come in and play something. And he played that great, gliding, jazzy, synth solo.

Cyrung, who plays the didgeridoo… To be honest, I can’t tell you how he came to be involved. It was through Geff and Sleazy… he might have been playing at a gig they went to, or something like that. Rose McDowall was a close friend of Geff’s in particular. They were very, very close. She only came in to do one song, which was called ‘Wrong Eye’ at the time and later became ‘Windowpane’. She was thrilled to hear what had been done to her vocals. When she heard them back later, she said, “What the fuck! Is that me? What’s going on in there?” Sleazy had done so much work, sort of collaging and changing the sound of her vocals, that she was almost unrecognisable, but she loved it.

Listening to ‘Wrong Eye’ (released on Stefan Jaworzyn’s Shock label, a spin off from his Shock Express magazine), it’s incredible to hear how the deranged lumbering chaos of that original track transformed into the glistening ecstasy of LSD anthem ‘Windowpane’, like a reverse Jekyll and Hyde. It’s a testament both to Coil’s studio alchemy, and the power of combining the right drugs with the right music.

ST: The other side of that Shock single was a piece called ‘Scope’, done at the same sessions. When Charles Hayward came in to record with us, he was setting up his kit and getting his drum sound with the engineer, and Sleazy was busily recording him while he was doing all this. By the time Charles was ready to start, Sleazy had already built up a bed of samples from Charles’ playing, and these became the backing for ‘Scope’.

After Charles left, I recorded the bass on ‘Scope’. I was absolutely soaked in E at the time, and yet that piece is one of the least E’d-up songs you can imagine. It’s so heavy and furious and clotted – but yeah, that was me on E basically!

Kudos to you all for being able to keep it together! Was there a particular studio you would use? I’m just thinking about how tolerant studios must have been, having these deranged-sounding sessions taking place.

ST: Nobody ever said anything. I mean, nobody ever complained. There were three or four studios that we went to during the course of Love’s Secret Domain, and I’d be hard-pressed to pin them all down. Matrix was one, Milo was another one; one of them was in Holborn near the British Museum, and another one was in Old Street.

I don’t know whether I would describe it as debauchery, but certainly I think most of the studios in the 80s were quite accustomed to seeing people who’d had a little bit of chemical assistance to get to where they wanted to go.

Coil, circa Love’s Secret Domain

Were there any contemporary musicians or bands that fed explicitly into Coil’s sound?

ST: I never really thought there were many bands that directly coloured our sound, to be honest. Maybe a little bit of Nurse With Wound, here and there, but I never really felt that Coil sounded very much like anyone else.

Exploring the possibilities of new technological developments can lead to similarities, but there weren’t many people who could afford to hire a Fairlight at that time, so Coil often sounded more like high-end arty pop, like Kate Bush or Peter Gabriel, than our experimental contemporaries.

Geff and I also both absolutely adored the Butthole Surfers: their musical world was so absolutely delirious and insane, but they had an amazing ability to pull it all together when they needed to. We were fascinated by them and the craziness that was kind of emanating from their sound. We saw them live several times – some of the best live shows I ever saw. Geff and I were just in awe: "Oh my God, this is what Coil gigs should be like!" But you know, obviously, we were musically a million miles removed from what they were doing but the derangement of it was so compelling. We hung out with the Buttholes several times, and Sleazy provided

them with their infamous penis surgery projections.

There was always a pop sensibility within Coil’s music, sometimes buried and sometimes right there on the surface. Given Sleazy’s video career inside the pop industry, was there any urge towards pop with Coil?

ST: Well there was no taboo about pop, there was no separation or a sense of, "We can’t do that, it’s too poppy." Nor was there a point where we’d say we want to be more like pop. The continuum was continuous! Our musical tastes ran across the board from pop to David Tudor, so there was no sense that you had to stop yourself from making a decision that might lead you anywhere along that continuum. There was no censorship of intent, there were no strictures or rules about where we should or shouldn’t go. We later came to disagree about certain strands that we were exploring, but when we were coming up with new musical ideas, or making musical decisions, it was all about the context of a particular piece or moment. There was no pressure to steer away from pop for fear of polluting the more experimental side of things.

Were there any approaches from the more commercial pop world to turn Coil into something else?

ST: No. We were too out and gay. At the time, Coil were a rare group in that our sexuality was a clear and present factor in our aesthetic, our music and our style. Nearly all of the other gay recording artists of the time were either fully in the closet or kind of, you know, coy and evasive on the subject. There were the Communards and us, I suppose, off the top of my head.

Did you have any support or interest from the gay community?

ST: No. One thing that used to annoy Geff in particular – I don’t think Sleazy cared so much – was that the gay press hardly ever paid any attention to Coil. It really was the cliche of, if you’re making disco bunny or house music then you might get covered in the gay press, but if you’re not doing something that appeals to that rather superficial aesthetic, which was the hallmark of the gay scene, they didn’t even deign to glance at you.

You were just the wrong kind of gays… Given that your cover of ‘Tainted Love’, and the themes of Horse Rotavator explicitly referred to what was happening with Aids at the time, it seems remarkable that you’d be ignored like that.

ST: Yes, you would have thought that the political act of releasing a single, ‘Tainted Love’, whose proceeds went to the Terrence Higgins Trust in 1985, would have gained some respect or acknowledgement from the gay press, but it didn’t – we were almost invisible to that world, certainly in its written form. We had gay fans obviously, who didn’t need the gay press to tell them what to take an interest in. But yeah, the gay press were really quite conservative in their musical scope.

Talking of disco bunnies, you’ve mentioned that Geff and Sleazy were enthusiastic clubbers, was that something you shared with them?

ST: I did go to a few clubs with them but I had a very utilitarian approach. When Aids and HIV started to impact on gay men’s lives, they started to spend more time on the dance floor, and being at the club itself became the be-all and end-all of clubbing. But I didn’t want to spend time listening to records I didn’t like played at ear-splitting volume. I was there to do something else entirely, so as soon as I could persuade somebody to leave with me, we’d be off!

But Geff and Sleazy enjoyed the clubs for themselves; also the backroom experience, which they were into more than I was. I always thought, you know, if the lights come up suddenly and it’s Charles Hawtrey, what am I going to do?

Stephen Thrower, portrait by Peter Christopherson, late 80s

It seemed like everything was being consumed by club culture at the time. Was there a sense of the club scene encroaching into Coil’s world?

ST: From my point of view at the time, yes, encroachment was the way I would have seen it. What we were saying earlier about having an open field as far as musical influence and musical appreciation was concerned, that was all part of it, and Geff and Sleazy definitely enjoyed the acid house and techno music played at those clubs a lot more than I did. I generally found most of the music quite boring, and they didn’t.

It’s the old musical differences thing, isn’t it? When that musical ingredient started turning up in the Coil mix, for them it was just a natural progression to be opening their parameters to include it as a possible route to take. To me, there was a kind of a homogenising element going on with that kind of music, lots of other groups started incorporating it into their sound, and when it started to have an influence on Geff and Sleazy’s musical choices, it sounded to me more like the music was swallowing them, rather than the other way around.

I didn’t like the idea that Coil were heading towards becoming part of it. I didn’t want to be like Spinal Tap, where you see the flashbacks to their earlier records, including their flower power single!

I can now listen to ‘The Snow’ on LSD from a detached perspective and quite enjoy it, in a toe-tapping sort of way. But at the time I just thought it sounded too much like a wholesale influence imported almost intact from another musical field instead of being perverted, twisted and spun in interesting ways.

‘Windowpane’ also absorbed some influence from dance music, though it’s slung very low and slow in comparison, while ‘Further Back And Faster’ also has an element, but it’s percolated through the technology in an interesting way.

Can you tell us about your departure from Coil?

ST: It was just people moving in different directions. And drugs moving in different directions… I was much speedier than they were. I was also entering a darker patch in my life, and maybe that was freaking them out.

The drug situation meant that things were always going to fall apart eventually. It’s very, very difficult to take colossal amounts of drugs, in different combinations, and not lose your mind at some point. I think it was inevitable, given how much we were shovelling into ourselves, that something was something was going to break eventually. I can’t really see how it could have been avoided, because the hedonism, and the experimentation, and the deliberate cultivation of delirium was all part of Coil’s raison d’etre. You couldn’t strip it away at that time and still have Coil, so it was inevitable really that we were going to crash and burn.

What’s funny is that my ending with Coil coincided with my partner Ossian Brown becoming their lodger in Chiswick. He and I got together around the time that I left Coil; he then moved in with me and we didn’t see Geff and Sleazy for several years. But because Geff and Ossian had been so close, their friendship reignited. And then obviously a few years later, Ossian ended up joining Coil himself, and Sleazy, Geff and I had a chance to kind of re-approach each other and start again.

Are there things that you took from working with Geff and Sleazy that you still carry with you to today?

ST: I think certainly my contributions to Cyclobe were informed by my experiences working with Geff and Sleazy, at a spontaneous, intuitive level rather than a technical or aesthetic one, although I did learn a lot technically from Sleazy during the Coil period, and that came in useful with Cyclobe and my work in UnicaZürn.

With Coil it was about trying to keep all of your options, all of your channels, open, so that what you ended up with was such a kaleidoscope that the music never sounded like it belonged too heavily to one strain of influence. And that’s something Ossian and I felt strongly about with Cyclobe: it’s fine to have influences, but you don’t really want the end result to feel like it’s been imprinted too heavily by any one of them. You hope that out of that openness to possibilities will come something else, that the openness itself, rather than the influences, ends up shaping the result.

Love’s Secret Domain remastered from original sources is available now on CD/DL from WaxTrax! Vinyl ships at the end of July