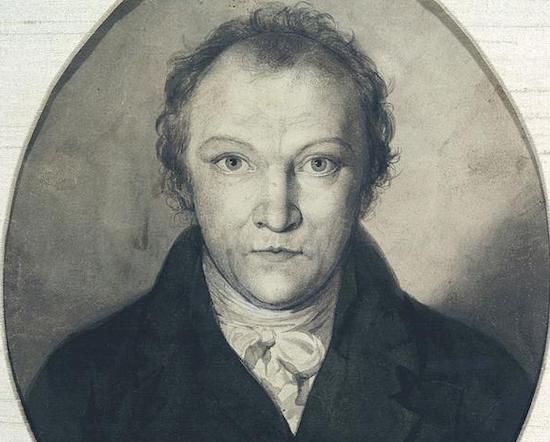

William Blake, the eighteenth-century poet, artist and visionary, is usually described as unique. There was no-one like him before and no-one remotely like him afterwards. His work was so baffling and his mind so neuroatypical, the thinking goes, that we can never hope to understand or label him. But this is not necessarily true. There have been other people who were mentally strikingly similar to Blake. His closest recent equivalent is the late Minneapolis musician Prince.

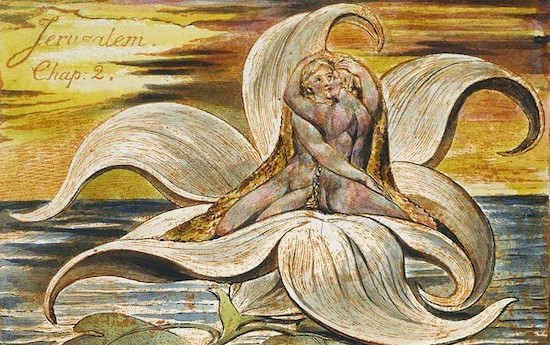

Prince and Blake were the products of very different worlds and they created very different art, of course, but they both saw beyond their contemporary circumstances and came to remarkably similar conclusions. The most prominent themes in their work are spiritual liberation and sexual freedom. They portrayed these not as opposites or contradictions, but as essential and related concepts – interlinked pathways that we need to follow, if we are find our way to paradise.

Blake and Prince were both visionaries. Blake’s most famous vision was probably the tree full of angels he saw on Peckham Rye when he was around eight-years-old. Prince also claimed that he was visited by angels as a child, and that they cured him of epilepsy.

Both men were compelled to create, regardless of whether there was an audience for the art being made. Blake produced an astonishing amount during his lifetime, despite being largely ignored, dismissed or patronised by his contemporaries. He saw the work itself as self-validating and the act of creation as divine – even if its only audience was the artist and the spirits. In a similar way, Prince had a compulsion to continually make music, winding down from his lengthy concerts by playing even longer sets at the aftershow parties. At his own Paisley Park studios, he had sound engineers on standby 24 hours a day, so that he could record whenever the urge came. Much of what he recorded has never had an audience – after being recorded, it was simply placed in his famous vault. Like Blake’s work, it was the act of creation that mattered. Presenting that work to an audience was secondary.

Then there is their unusual genius across different mediums. Blake has entered the canon as both a poet and a painter of genius, a situation entirely without precedent in the history of art. Prince was untouchable as a writer, performer, vocalist and as a producer, and he was the master of every instrument he touched. In the field of music, there was nothing he could not do. In a manner that remains phenomenally rare, both Prince and Blake possessed a genius separate from the medium that they used to express themselves, which was capable of using many different forms and tools.

In Blake’s mythology, his male characters generate both a female emanation and an evil shadow he called the Spectre. The Spectre is your dark side, the side of your personality that is cut off from the light and contains all your doubt and self-hatred. These characters, as Blake saw it, were the personifications of different aspects of our minds. In the mid-80s, Prince also generated a female or androgynous emanation, whom he called Camille, and a devil-like figure who was the distillation of his dark side, whom he called Spooky Electric.

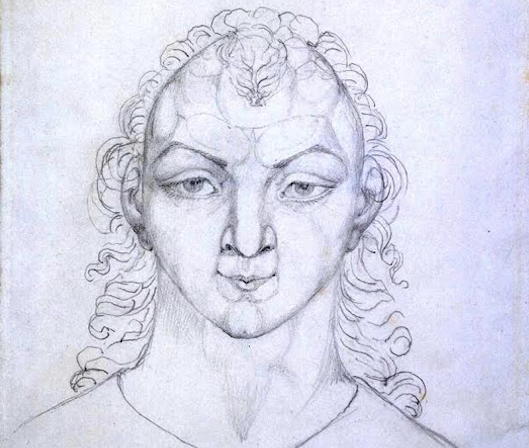

Camille manifested through Prince singing in a pitched-up voice. She was the original driving force behind his original 1987 follow up to Sign O’ The Times, a record known as The Black Album. A ‘spiritual self-portrait’ that Blake drew after 1818 shows a more feminine version of his face, which is especially striking when compared to an earlier self-portrait. It suggests that Blake, like Prince, may also have had an androgynous alter ego, in the spiritual realm at least.

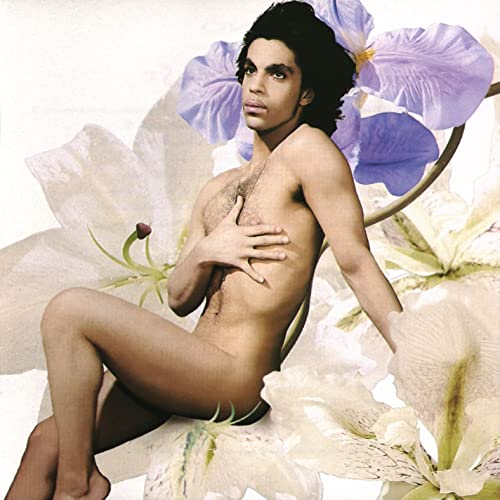

A week before release, and after initial copies had been printed, Prince had The Black Album withdrawn. This turned it into one of the most bootlegged albums in history. He did this, he claimed, because he realised that the album was evil, and that the real driving force behind it had been Spooky Electric. To make amends, he returned to the studio and recorded an album of love and positivity, the crowning achievement of his golden period – his masterpiece Lovesexy.

The contrast between The Black Album and Lovesexy was profoundly Blakean, for Blake insisted on the necessity of opposites, claiming that “Without contraries is no progression.” There is a key difference here, however – Blake wouldn’t have withdrawn The Black Album. Instead, he would have put it out paired with Lovesexy, much as he did with the contrasting Songs of Innocence and of Experience. In the video for Lovesexy’s lead single ‘Alphabet St’., Prince hid the message “DON’T BUY THE BLACK ALBUM, I’M SORRY”. Blake would have recognised that the album was indeed the work of Spooky Electric, but he would never have apologised for this.

The more you look at the work of Blake and Prince, the more you notice that they are trying to express the same concepts. What could be more Blakean than Lovesexy’s ‘Eye Wish U Heaven’? What could be more Prince-like than Blake’s claim that ”Energy is eternal delight”? Blake wrote of revolution and apocalypse, just as, in 1999, Prince’s band The Revolution soundtracked the party before the end of the world. In ‘Alphabet St.’ Prince sings, “Put the right letters together, and make a better day,” which could have been William Blake’s mission statement. When Prince wrote ‘slave’ across his face, he was showing his awareness of Blake’s “mind forged manacles”. Contemporary scholars agree that William Blake absolutely was hip to the rare ‘Housequake’.

If we view both of these geniuses as unique one-offs, it is easy to shrug and dismiss them as people we can never understand. They are outside of all categories, and as such remain anomalies in our understanding of both human psychology and creativity. But when we start seeing them as psychologically similar, this gives us great new insights – boh into what Blake can tell us about Prince, and what Prince can tell us about William Blake.

These were two men who acted as portals for unfiltered imagination and creativity, which flowed through them and, in doing so, enchanted the mundane world. The experience of being powerless in the face of such overwhelming imagination was profoundly spiritual for both of them, and it gave them an understanding of spirituality that was physical and rooted in the body. There is a pattern here, and it seems worth paying attention to. Perhaps if we pay attention to what Prince and Blake were trying to tell us, then we will be less confused and more appreciative when, hopefully in the not-too-distant future, the next of their kind comes among us.

William Blake Versus The World by John Higgs is out now via W&N Hardback, audio and eBook