On a basic level, there are perhaps two major regions of the science fiction landscape. A number of stories attempt to explore how we and our preconceptions change as our experience broadens. Other stories foresee how future experience will affirm entrenched ideas with cosmic impact. One of the most entertaining of these old ideas is Hell. "Hell", explains a sinister Sam Neill – thesping firmly from that latter side of the canon – "is just a word. The reality is much, much worse."

The film is Event Horizon – Paul W.S. Anderson’s 1997 ‘haunted-house-in-space’ opus that, judging by evidence, knocked the ascendant director’s career from orbit. It was a commercial and – to a large extent – critical, misfire, succeeded by a string of deserving flops and franchise tie-ins (think Soldier, Alien Vs Predator, the Resident Evil series). It has since developed a cult following, but remains cruelly overlooked for the milestone that it is – in terms of its aesthetic, its accomplished synthesis of elements, and in how well it has aged over the years.

About an unaccountably derelict star ship mysteriously returned from a seven year voyage through a black hole, the movie’s heritage can be traced back most definitively to the Disney classic The Black Hole. In that earlier film (30 years old this year), Joseph Bottoms glances through a porthole at an unnerving triumph of seventies special effects, and observes "Every time I see one of those things I expect to see some guy in red with horns and a pitchfork." Both films harvest the metaphysical import that we attribute to these enigmatic space phenomena. They are "the most destructive force in the universe", warns Event Horizon’s lieutenant Starck (played solemnly by Joely Richardson), and – as far as our knowledge goes – great wells into oblivion. Through the cinematic lens we’re returned at once to old myths of the sea dropping off the edge of the world, and to reflections from the void of whichever religious archetypes we choose to project in place of our understanding. In the earlier film, the black hole plays centre stage in a funeral ritual, receiving the coffin of a dead sentry. Anderson takes this kind of reverence about as far as is possible.

The Event Horizon spacecraft was shaped to resemble an altar, and in design was allegedly a composite of scanned photographs of the Notre Dame Cathedral, reconfigured like lego blocks and then rendered in metal. From the movie’s vertiginous opening shot where we pitch down towards it – with the gas giant Neptune churning immensely (and silently) in the background – it makes for a more than imposing precedent for what’s to follow. We’ve routinely been launching spacecraft into the celluloid cosmos for decades, but how many as visually striking as the Event Horizon?

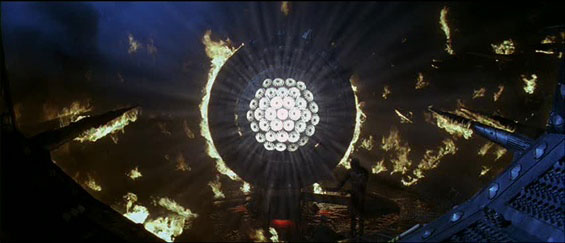

Its crucifix-like shapes, dark, slitted windows and looming turrets present a gothic malevolence difficult to misinterpret, but inside Anderson seemed intent on creating a much less graspable environment. Perhaps in homage to acknowledged influence The Haunting – where the demonic house was all off-kilter angles and asymmetry – Event Horizon’s interiors were complex multi-levelled constructions, many of the walls and surfaces curved (the iconic ‘First Containment’ passage in fact rotating). Coupled with this was the director’s keenness on ‘circularity’. The reveal of the Daylight space station near the beginning – where we pull back from a window and spiral outwards into space – has a literally dizzying power. But rather than functioning as a one-off set-piece shot, this visual style becomes a motif as the movie progresses. Cinematographer Adrian Biddle’s cameras spend much of their time literally prowling in circles round the characters, or swooping in lopsided arcs around the Event Horizon’s innards (which resemble a kind of art-deco mortuary). Some of this was to simulate the disorientating impression of freefall, but the sum effect was a kinetic-feeling environment that it’s impossible to assemble a mental shape of.

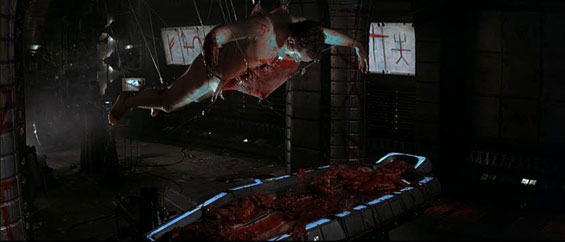

This leads to a mounting atmosphere of permanent unease, with shock moments liberally thrown in to escalate it. The most enduring of these are the scattering of ‘visions’ unleashed by the ship upon the characters, giving impressions of its journey. They last for frames at a time, and portray an apparent orgy of rape, mutilation, cannibalism, impalement, maggots and other such niceties. A great deal of footage was shot for what, in the final cut, amounted to about twenty seconds worth of glimpses. Unused stock exists in various forms of decay: at the time of release DVD extras weren’t a particular consideration and Paramount had little inclination to retain unused footage from the commercially unsuccessful film. This is a good and bad thing. Bad in that it’s always sad to lose artifacts in this way. On the other hand – with most films warranting about eight ‘definitive’ re-cuts post-release – it feels like a kind of bonus to be able to buy a ‘collector’s edition’ that matches for content what cinema-goers experienced.

Those experiences were of course over a decade ago – a pretty good distance from which to judge how well a movie has aged. Any longer and we’re looking back with a detached fondness for the era; shorter and we’re essentially still part of it. Promoting Event Horizon’s release, magazine spreads conveyed the quality of CGI employed for its signature composite shots (take the Daylight pull-back sequence, for instance), in how many thousands of floppy discs would be filled by the data. What comes across now is how meticulously those sequences seem to reflect the year’s worth of time and effort invested in them, resulting in imagery with the impact of key scenes from films like 2001: A Space Odyssey and Blade Runner.

A further boon to the film’s posterity is its elegant arrangement as a narrative. Philip Eisener’s original script was allegedly dense and complex, with the shipboard evil in the form of tentacular creatures that had stowed away onboard during its interdimensional excursion. Many of these specifics were pared down for a more elemental story, enigmatic in its vagaries, but hovering (as The Shining did) on just the right side of frustrating. In the scene where Laurence Fishburne describes to Jason Issacs the destructive beauty of fire in zero gravity, Anderson forgoes the almost obligatory flashback sequence, and we’re left in Event Horizon’s aftermath trawling other sources for a visual corroboration for the terms used (there’s a good example in Andrei Ujica’s otherwise unengaging documentary of life aboard the Mir Space Station, Out Of The Present, incidentally). In Anderson’s film, the ship became the real character, the flesh and blood characters rather, types (the stoic captain, morbid doctor, Faustian genius, wisecracking black guy, etc.) However, a strong ensemble performance from a talented cast breathes real life into Eisener’s and Andrew Kevin Walker’s often stilted dialogue ("The dark inside me…from the other place"), adding a dimension of genuine empathy and believability to the embattled salvage team. It’s in this area (essentially – smart casting) where, above a number of glaring aesthetic similarities, Event Horizon best compares to Ridley Scott’s Alien.

Anderson was barely in his thirties when he made Event Horizon, in itself a kind of cathedral to his horror and sci-fi influences. An amusing moment on the movie’s DVD extras is a deleted scene of Sam Neill’s ‘Weirbeast’ creature crawling in spiderlike fashion down a ladder. It was intended to evoke a scene that was itself removed from the original cut of The Exorcist.

Event Horizon, in turn, has an inescapable influence on subsequent films that have strayed into that ‘haunted-house-in-space’ sub-category of sci-fi horror (take Sunshine, for instance), though few would easily acknowledge the debt and, arguably, none since have surpassed it.

As a producer, Anderson did unsuccessfully attempt that very feat a couple of weeks ago with sci-fi chiller Pandorum. From him now, we look forward to Resident Evil: Afterlife due out next Autumn, and accept that the talented director who built and burned this entrancing world within Pinewood studios in the mid-nineties is currently living his own kind of afterlife.