The algorithms that dictate so much of our consumption – the next song you listen to, the next film you watch, the next person you go on a date with – are now so complex that they are approaching the point where not even their creators can comprehend them. “One of the biggest sources of anxiety about AI is not that it will turn against us, but that we simply cannot understand how it works,” wrote the Harvard Business Review in 2019. Algorithms now make so many decisions without consulting the people they effect, wrote Towards Data Science in a lengthy essay on the need for increased ethics in the field, that “they have become the decision makers, and humans have been pushed into an artefact shaped by technology.”

This uneasy war of wills between human and machine is one explored by Alexander Tucker on his debut album as Microcorps, XMIT. The title, which can be pronounced as ‘transmit’, refers to “a time in which information both physical and nonphysical transfers at an alarming rate beyond human comprehension into an age which is at once banal and terrifyingly alien,” as he put it in material that announced the album. “Alan Moore has talked about the period of time that we’re in at the moment as ‘The Age of Steam’,” Tucker expands on a video call. “There’s so much information that it’s an incomprehensible steam. I think that’s why you’re getting all these mutations appearing both physical and non-physical, conspiracy theories that are becoming quite dangerous and ugly and nasty. It is quite terrifying, I think.”

The very way in which XMIT was made evokes those debates. Tucker combined drums with a preamp module into which he could plug his cello, electronics and vocals. “With each patch you can find a whole new set of variables,” he explains. “So it’s very hard to repeat. Even if you wrote it down and went back in again it wouldn’t sound the same, it seems to have a mind of its own in some respects.” Until now he’d avoided working with modular systems, “because it seemed just as bad as guitar blokes doing ‘Stairway To Heaven’ demoes online,” but his mind changed as he engaged with the music of friends like Nik Void, Chris Carter, and particularly Mute Records boss Daniel Miller, who performed a short modular set for his wedding guests, the day after the ceremony. “Because I was standing directly behind him, I could get a sense of how he was doing what he was doing, how drum modules are processed through the system, so you can get all sorts of different animations and sounds and basslines and events happening through the patch that you make, and then through different variables. They’re pretty juicy machines.”

It’s not too much of a stretch to connect the way in which the music on Microcorps was composed, to some extent expanding and evolving under its own momentum once Tucker sets it off, with the loss of human control that characterises ‘The Age Of Steam’. “There are these incredibly complex machines leading you down paths,” he says. “You’re partly in control and you’re partly out of control, but you’re out of control through the decisions you’ve made yourself. Luckily in this scenario it’s a joyful outcome. I could spend three days working on one patch and do a bunch of takes and they’re all different every time. The parameters are set but it can still move around, and you’re injecting different sounds at different points. It sits between improvisation and composition, they’re both inhabiting the same space, which is great because they’re the two things I absolutely love doing in music.”

Making modular music is a lot like painting, continues Tucker, who is also a visual artist. “You’re laying brush strokes on, patching in different ways, you get something and it looks great so you work into it, then you lose it again, then you work again, and you start to see something that’s yours and suddenly you’ve got a picture. You can be working on one thing for ages and then you have to wipe out the whole thing and start again. It’s a facet of the creative process.”

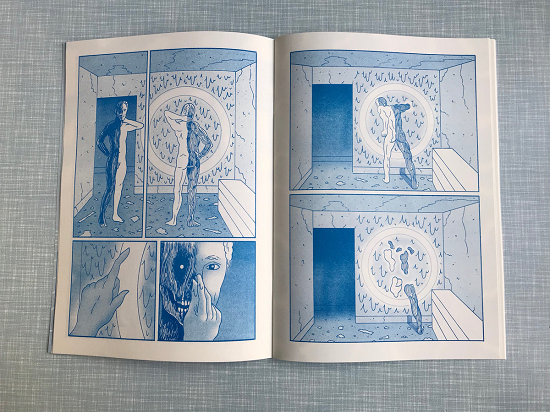

When the UK first went into lockdown in March 2020, Tucker found himself drawn to visual art far more than music. The latter felt “superfluous” in those weird early days, he explains. “All this horrible shit’s going on and people are dying and I’m sitting around making entertainment?” He took the time to work on a comic called Entity Reunion 2. “Of course, a comic is entertainment too, but it’s also just mapping out a world. It’s like it ever is when you’re a little kid, you’re putting your head down and drawing and immersing yourself in that world, blotting out reality.” The seed of the idea was “that thing in dreams when you’re seeing yourself and you’re also the protagonist, so there’s these two doppelganger entities that are viewing one another.” Those two figures are corpse-like, their bodies skinless and flayed down one side, “so I introduced this cartoony blob-headed character, just to lighten it up a little bit.” Another character in the comic was inspired by ‘Judy’, the grey, faceless, all-powerful malevolent entity from David Lynch’s Twin Peaks; The Return. “She’s the ultimate being, you can’t beat her, you can’t fuck with her, she controls time and space.”

From Entity Reunion 2

Tucker’s Judy figure also appears on the front cover of XMIT. What links the two projects together, he says, is “that obsession with entities and characters.” Having recorded all his solo music under his birth name since his 2005 self-titled record, “I just really wanted to get away from Alexander Tucker,” he says. “Even with Grumbling Fur,” his band with Daniel O’Sullivan for which he’s perhaps best known, “Alexander Tucker’s still very much a character within that band.” A couple of years ago, the musician made “a few changes” in his life, the specifics of which he won’t go into, “and suddenly woke up from this strange dream of the Alexander Tucker years.”

There was a degree of separation in those days, he goes by Alex in ‘real life’, not Alexander, but it wasn’t that big. “I remember someone once saying they envisage Alexander Tucker wandering around deserted coastlines, picking up obscure objects, and I was like, well that is my fucking life! I would just wander around, listening to music in slightly altered states, thinking about and drawing upon my surroundings, then I’d pour that into the music. There was definitely a lot of struggle and unhappiness that I was dealing with too, and pouring into the music. I was struggling for years and years with moving out from Kent and up to London, and I’ve lived here since 1997. Now I don’t really feel that’s as present as it was.”

Though its harsh, pummelling kinetic beats are incredibly intense, the most notable thing about XMIT is Tucker’s approach to vocals. His own voice is stretched and re-pitched to the point it becomes either a booming drone or something high, ethereal and ghostly; they are “alternate entity versions of myself,” the musician puts it. The figures he creates on the record, humanoid but not quite human, represent that break he sought with the Alexander Tucker of old.

There are collaborators on XMIT too. An admirer of the way in which Gazelle Twin’s voice is often pitched in an eerie, androgynous zone, he asked her to record something inspired by the Alien films, of which they’re both fans. She provided dark and looming vocals “that sounded like a xenomorph being born, or a victim of the xenomorph” for him to process further. “She said she wanted it to sound like someone stuck in the vacuum of space.” Simon Fisher Turner, another artist Tucker admired for his harsh approach to the human voice, sent over “these weird, choked, guttural vocals. I processed them a bit, sent them back to him, then he sent me some complete concrete harsh ambient noise stuff that he’d made from my processed stuff and his voice.” Nik Void, one of his role models when first approaching modular work, provided guitar noise processed through her own systems, while Astrud Steehouder responded to a particularly brutal track he sent her with “something beautiful and fragile amongst this maelstrom of noises and beats.”

If you didn’t know who those collaborators were, you’d have a hard time guessing. When any understandable words emerge from Gazelle Twin and Simon Fisher Turner’s contributions, or in fact from Tucker’s own vocals across the album, they are fragmented and often hard to make out. The names of the songs themselves occupy a similarly liminal space between intelligibility and obscurity, like ‘JFET’, ‘DOR’ and ‘XEM’. “They’re playing around with language, seeing how I can reduce it, expand it, and also leave it quite open,” Tucker says.

One of the album’s key themes is the effect that this can have, how the filing down of language to its very core can be so dramatic that it alters our perception of the world around us. “The idea was to take language back down into a primordial state of pure sonics,” Tucker explains. “The idea of turning language into pure sound brings something more akin to early humans, and that opens up a shift in perception.” Though it’s a little trite to talk about music as a ‘universal language’, there’s something in it. “I’ve always liked it when anthropologists talk about how early humans were mimicking bird calls and how language came out of that, how it literally came out of pure sound.”

He’s currently working on a new ‘cut-up drone’ trio with Steehouder and Luke J Murray, a project incorporating recordings by the late actor and artist Keith Collins, partially recorded at Derek Jarman’s Prospect Cottage, and there’s a “long-languishing” Grumbling Fur album in the pipeline. But with XMIT Tucker has formed something quite separate from all that. With Microcorps he’s not just shifting away from his old self, but creating something new entirely, an entire universe inhabited by strange figures, part human and part machine, speaking in a language both recognisable and alien that seems to evolve and change outside of their creator’s control. “It’s music,” he says, “that will hopefully shift perceptions.”

Microcorps’ XMIT is released on April 16 via Alter. You can pre-order it here. Tucker’s comic, Entity Reunion 2 is available here.