Earlier this week, French house pioneers Daft Punk bid adieu to the world after 28 years atop the throne of international dance music. By the time their reign had ended, Thomas Bangalter and Guy-Manuel de Homem-Christo became household names both in and outside the electronic music scene, setting themselves apart with a pair of instantly iconic robotic suits and a seemingly boundless appetite for pushing their beats into previously unexplored territory. After nearly three decades of grooving through nearly every genre and form imaginable, it would have made perfect sense for the duo to go out on a note as joyful and celebratory as their own music. Instead, they said farewell with a somber eight-minute clip from a relatively little-seen silent film they shot in the California desert: Daft Punk’s Electroma. With this, the pair confirmed that the project that might seem like a footnote in their career lays the groundwork for what made the world’s most famous French robots so deeply human.

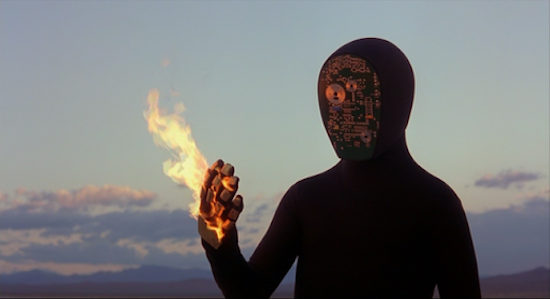

The scene in question forms the climax of Electroma. After attempting to become “human” via a surreal procedure which renders the pair into grotesque, latex caricatures of their real selves, Bangalter and Homem-Christo’s personas (played here by Peter Hurteau and Michael Reich) are rejected by the nearby robot community. Their human masks melt, and they enter self-imposed exile in the salt flats of Death Valley. After walking for a long, undetermined amount of time, Bangalter stops, removes his jacket, and silently implores Homem-Christo to flick an ominous switch on his back. Homem-Christo complies, a countdown begins, and Bangalter steadily walks to his doom. He explodes, leaving his companion alone in the wastes.

It’s an oddly moving scene, which profoundly affected me as an impressionable young fan of the duo. After years of only listening to what my music-obsessed dad shared with me, I discovered Daft Punk on an internet message board and was instantly hooked. The pair’s mysterious allure, mad experiments with sound, and my mum relaying stories of clubbing to ‘One More Time’, caught my attention in a way only one other thing did at the time: movies. When I was perusing the aisles of my local video store and saw a steelbook DVD case depicting two shrouded figures standing under the words Daft Punk’s Electroma, I felt overwhelmed imagining all the wild directions my new favourite musicians would take a film.

When the credits rolled after my first watch, I remember feeling like I had been let in on some great secret of the universe. Growing up living off the likes of Spielberg, Cameron, and the Wachowskis, I had never seen anything like Electroma. I didn’t care that none of the duo’s music was in the film, that it had no dialogue, or that it was excessively slow. I had just been given my first taste of the avant-garde tradition, opening my eyes to a whole new world of film just as I had been introduced to a whole new world of music. Most importantly, I felt like I finally understood who Daft Punk really were; before Electroma, even the already obsessed fan in me thought the robot stuff was just a neat schtick. Now I saw the costumes, and thematic elements of their music, in a new light, understanding their mission as musicians was to find humanity in an often cold world. Suddenly, Human After All wasn’t just an album title anymore.

The robot personas that Daft Punk turned into timeless iconography had no deeper meaning at first. They conceived the costumes in the lead-up to their breakout 2001 album Discovery, joking they accidentally became robots while recording that album, and largely left it at that. The suits conceived by special effects designer Tony Gardner were simply the latest in a long line of disguises the pair used while performing and promoting themselves. Human After All was a sea change, marking the first time they considered their costumes integral to their identity. While light on actual lyrics, the album is jam-packed with motifs describing an identity war, the longing for connection versus the programmed callousness of the digital age. The title track offers a repeated affirmation of the robots convincing themselves they have the ability to feel human connection. ‘Television Rules the Nation’ reworks ‘Around the World’, a seminal track from their debut album Homework, into a propaganda anthem for the looming presence of mass media. ‘Technologic’ warns of the hypnotism of living to work instead of working to live. If the themes found in Human After All lit the sparks of what was to come in the latter half of Daft Punk’s career, Electroma was the resulting fire. The anxieties of the album come to life chillingly in the film, as Bangalter and Homem-Christo’s soul-searching robots navigate a world of leering neighbours and the lingering air of conformity.

After Electroma, the struggle for human autonomy inspired everything the pair did. The set of their now legendary live tour Alive 2007 opened with a robot consciousness arguing with itself that it was indeed human. They found kinship in the conflicting human and digital realities of Disney’s blockbuster sequel TRON Legacy, sculpting that film’s score into a sprawling and emotional push and pull between the dance stylings of their early career and grand, operatic orchestrations. Bangalter described their 2013 disco-electronic-fusion masterwork Random Access Memories as an album about the brain as a hard drive, departing from their earlier work by swapping out mixing samples for live studio collaborations with collaborators including Giorgio Moroder, Niles Rogers, and Pharrell Williams but keeping the ambition of searching for human connection in the Information Age’s constant stream of ideas.

Bangalter and Homem-Christo’s cinephilia formed Electroma into a transformative experience for them, as their love of films was already hardwired into their identities long before the film was even conceived. Much of their music has been described by the pair as a love letter to the memories of films they bonded over in children, principally Brian De Palma’s satirical rock opera Phantom of the Paradise. Two other film projects they’ve worked on – the music video collection DAFT: A Story About Dogs, Androids, Firemen and Tomatoes and Discovery’s extended anime tie-in Interstella 5555: The 5tory of the 5ecret 5tar 5ystem – are steeped in the pair’s seemingly vast knowledge of international cinema and television. DAFT boasts direction from a collection of beloved auteurs ranging from Spike Jonze to Michel Gondry, while Interstella 5555 was born from a collaboration with the pair’s childhood hero Leiji Matsumoto, who has penned innumerable space opera manga and anime.

Electroma is unique in that it was the first and only film that was entirely Daft Punk’s own organism; they penned the script, co-directed, and Bangalter served as cinematographer, spending pre-production reading over 200 copies of the filmmaking magazine American Cinematographer to prepare. Electroma is no mere promotional add-on from Human After All; it’s a fully-formed feature with shades of independent cinema running through its circuited veins. The horrific, surreal masks the pair don in order to appear human mimic the nightmarish imagery of David Lynch’s Inland Empire. The robots’ ill-fated journey into the desert mirrors the doomed trip that forms the center of Gus Van Sant’s Gerry. The twisted depictions of suburbia and the otherworldly image of Homem-Christo wandering the wasteland alone evokes the mood of Derek Jarman’s The Garden. Through this confluence of cinematic flourishes, Electroma quietly highlights what Daft Punk’s discography was always trying to: conformity is an ironically surreal prison, and the only way to free ourselves is to let go and feel the music. Otherwise, we self-destruct.

This idea has been cemented by the duo’s use of the film’s climactic scene as a eulogy for their career, with some noticeable tweaks to the original film further emphasising Electroma’s importance to their legacy. The original film ends with Homem-Christo’s lonely robot giving into despair over the death of his silver-domed partner, sealing his own fate by smashing his helmet and using the broken glass to set himself ablaze in the desert sun. The new epilogue now gives the pair a more bittersweet ending, holding on to Homem-Christo walking off into the sunset, the hauntingly beautiful choral section of their Random Access Memories track ‘Touch’ sending him on his way. “Hold on, if love is the answer you’re home” croons over and over as 28 years of history are summarized in a few poignant frames. The newly formed juxtaposition of music and imagery affirms the romantic humanism that runs through these funky robots’ souls, reminding us of their career-long belief that our connections to one another, whether through music or other means, form the basis of our souls. By repurposing Electroma in this way, Daft Punk said goodbye with their motherboards laid bare for all the world to see.

Much will rightfully be written about Daft Punk’s musical output in the coming weeks, but their cinematic output shouldn’t be ignored. Electroma, in particular, offered a gateway to cinematic history beyond the mainstream, putting the duo’s forebears in direct conversation with the contemporary. It crystallised Bangalter and Homem-Christo as great purveyors of the human experience not just through their music, but through every sense of what it means to be alive. They visualised everything they were feeling and subsequently imparted the lessons of that experience to us, as they always graciously did. On the strength of that gift alone, the spirit of Daft Punk will live on forever.