In 1971, Jake Thackray made a documentary for ITN about a valley in North Yorkshire called Swaledale. He is recognised in the program and asked if he is Jake Thackray to which he replies, “Sometimes… more or less.” It feels almost heretical to write a summation of his work. He said of his songs, “Nothing is real here, everything is a pack of lies”, and that “I’ve no interest in my autobiography. I’ve read it.”

You can treat this piece, then, like a gallop through Jake’s life. I chose not necessarily an inventory of his best songs but the ones that give an idea of the man and his dynamic, confused artistic voice. There was always going to be so much I’d have to leave out but it still pains me not to discuss the lilting beauty of ‘Joseph’, as beautiful as anything Nick Drake ever recorded, or ‘The Remembrance’ AKA The Greatest Anti-war Song Of All Time.

Biography is usually of little interest when writing about art. However, when an attempt is made by the artist to self-mythologise or distance themselves from biography, a la Tom Waits or Frida Kahlo, I see it as becoming part of the work. For someone who worked so hard to distance himself from attention, it seems fitting to give a summation of Jake Thackray’s music through his life. Indeed, his work often ended up echoing or anticipating what he later became. In ‘Lah Di Dah’ he makes a promise to “keep off the pale ale”, but he died an alcoholic. Similarly, in a superb radio program called Jake Thackray – The Yorkshire Chansonnier, Cerys Matthews notes that Jake became the village scallywag he sang about, eventually becoming the subject, rather than observer, of stories.

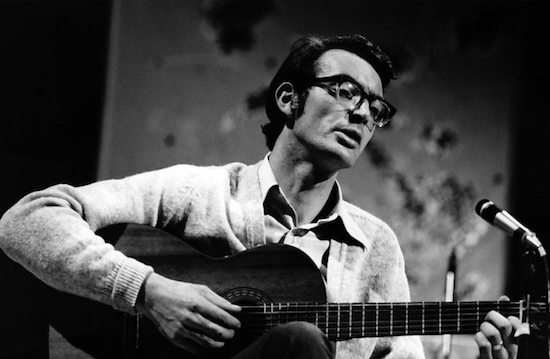

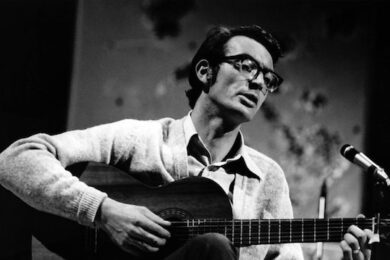

Jake’s music can be difficult to summarise. Even in terms of nomenclature, in the way Lou Reed is “Lou” and David Bowie “Bowie”, sometimes it seems more appropriate to say “Jake” and sometimes “Thackray”. Each studio album is less a sustained aesthetic thrust and more a collection of songs. Compilations and live albums outweigh studio albums by three to one. The task is made harder by how, when performed live, Jake’s songs were accompanied by addenda like lyric changes, stories, and jokes. Can that deliciously rueful look to the side when he sings “fine warm wool for a gentleman’s shoulders”’ during ‘Old Molly Metcalfe’ be counted as part of the music? There are the postmodern introductions he’d write such as “I spend my time voting conservative and lying to audiences”, or “this song could be called ‘The Solider’, I call it the prisoner”. Even as a life-long devotee, nay vocal evangelist, of stony-faced silence in between live music, I can’t help but love his patter, or what he called, “the drivel you’re supposed to talk between songs”. This sense of Jake existing alone is explained by some of his contradictions. He’s a performer who didn’t want to be a performer that rarely performed (once explaining his absence at a gig in August because of a snow drift). A musician that reportedly would have preferred to be a writer, his lyrics are enjoyably prolix, full of dazzling wordplay, peculiar phrasing, puns, and virtuoso rhyming.

Jake Thackray details the place where the small, the humdrum, and the grotesque intermingle, like the shepherdess frozen with her sheep, the wretched pub-goers’s wrecked lament, the deviant cockerel, and the park statues that spring to life after dark. From playing an unpopular instrument (a nylon-stringed guitar), to his baritone voice, to his thick, clipped Yorkshire brogue, and his mix of the profound and the profane, the comic brio veined with melancholy, he remains, “sometimes… more or less” an original.

‘Last Will And Testament Of Jake Thackray’ from The Last Will and Testament of Jake Thackray (1967)

That Jake Thackray’s debut album is called The Last Will And Testament Of Jake Thackray is some indication of how his music can seamlessly entwine the poignant and the grim. An enjoyable subversion of the youthful promise a debut album usually entails, the titular track is a blackly jubilant death note delivered in Jake’s inimitable style.

Let’s not forget this is a song and not an actual will, but it still presents an interesting idea of a total personal disintegration after death (incidentally a very un-English treatment of the subject). He encourages us to “let my memory slip” and wants “no epitaphs” (sorry, dude). Musically it has the apocalyptically, exultantly eulogistic feel of Nick Cave’s ‘Lay Me Low’ or even The Sensational Alex Harvey Band’s rendition of ‘Delilah’, moving between plodding contemplation to an anthemic double-time rhythm that feels like a bittersweet adieu.

You can equate ‘The Last Will And Testament Of Jake Thackray’ with Jake’s turbulent relationship with his art. The line encouraging “no keep-sakes” hints at how he was content to think of his music as ephemeral, even throwaway. Performing live he’d say things like: “It’s another silly song” or “It’s just a story and I’ve tarted it up a bit. See what you think.” Though perhaps intentional on his part, Jake doesn’t seem to have any confidence in his music’s lasting quality. I doubt he’d even have recorded anything if he hadn’t been contracted as, in his words, a “performing dick”. Perhaps he felt like a teacher from Leeds in the music industry and a “performing dick” in the real world. He squared this by treating his songs as if they were nothings, ditties, fluff. This all means there’s a tension between the surface level of Jake Thackray’s songs and the deeper merit he himself was maybe unaware of. Like all his best work, ‘Last Will And Testament’ uses humour to allude to a deeper melancholy, arriving at something bracingly consoling.

“Your rosebuds are numbered;

Gather them now for rosebuds’ sake.

And if your hands aren’t too encumbered

Gather a bud or two for Jake.”

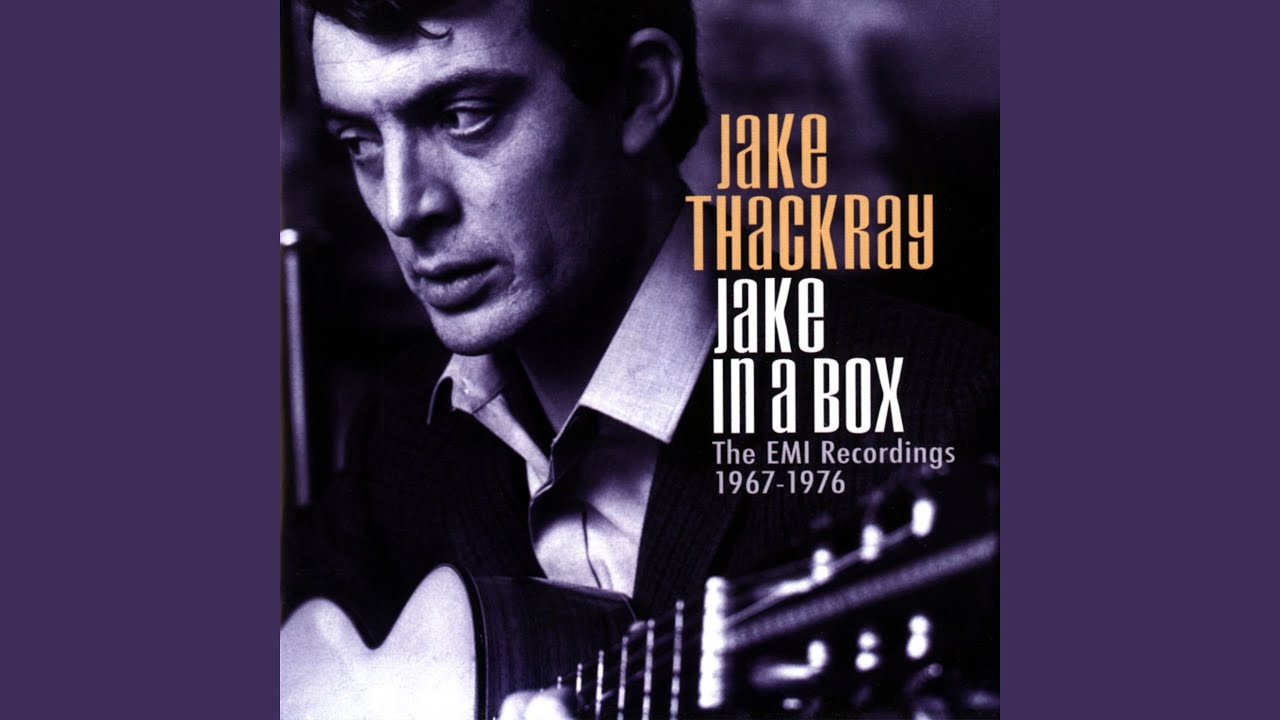

‘Kirkstall Road Girl’ from Jake In A Box: The EMI Recordings 1967-76 (2006)

These days, Kirkstall Road is indistinguishable from any other busy A-road in Britain (I used to live by it). Walking along it you’ll see supermarkets, gyms, and, incidentally, a shop called ‘Tyrannosaurus Pets’. But according to Jake Thackray’s song ‘Kirkstall Road Girl’, it used to be the kind of place that, if you lived there, it defined you, and probably not in a good way.

‘Kirkstall Road Girl’ is ostensibly a throwaway ditty, a sly poke at those who get ideas above their station. It’s a classic Thackray character study, the girl swapping “chips and cocoa” for “marron glace suppers”. Attempts to distance oneself from one’s past are usually futile, and the song is an interesting analogue for Jake’s attempts to paint himself as a rural boy from the Dales. He often tried to distance himself from his working class background. His real name is John, taking the name Jake after a French relative titled a letter to him ‘Jacques’.

I don’t think Jake was ashamed of his humble roots but he still made attempts to obscure this with what his old agent called “clouds of half-truths” and “lies”. He wrote lyrics rooted in a bucolic sensibility about country buses, foals, and farms, a far cry from Leeds’ industrial seethe. Although one finds it hard to imagine Jake eating a marron glace supper, ‘Kirkstall Road Girl’ is still a nuanced depiction of the ways everyone, more or less, attempts to circumvent their upbringing.

‘Go Little Swale’ from Bantam Cock (1972)

If Leeds was somewhere to escape from then the Yorkshire Dales were somewhere to escape to. Jake Thackray’s Swaledale was similar to James Joyce’s Dublin: a quasi-magical place rooted in a real geography containing the world’s multitudes. The superb BBC Jake In A Box documentary describes how he insinuated he was a country lad, which could explain the near-fetishisation of that area in his songs. His father, Earnest Thackray, was a policeman and had to move the family regularly from place to place. This somewhat nomadic existence contrasts the staid country life described in many songs about that area (‘Fine Bay Pony’, ‘Brigadier’, etc). ‘Go Little Swale’ is the most perfect combination of the particular and poetic. It presents a beautifully-rendered image of a river flowing past a fragmenting, non-physical landscape. The stationary old men who “stare at the dead afternoons” seem at odds with the children “learning to leave [the Dales] behind”. There’s a particular sense of place, “By Booze, by Muker, by Gunnerside, by Crackpot”, which is accompanied by the feeling that a way of life is disappearing. ‘Go Little Swale’ is hurried along by filigree guitar melodies with the same cascading rhythms as the river itself. It’s a delicate, feather-light ode to the place Jake loved.

‘Brother Gorilla’ from Bantam Cock (1972)

An important moment in Jake’s artistic development was his move to France and subsequent infatuation with French music. This is one of the reasons he seems detached from Western pop heritage. He lived in France during the early 1960s which is a key time in British guitar music. Furthermore, in the 1970s and late 1960s, when Jake was writing songs about scallywags, pubs, and jumble sales, groups were looking further abroad to India and America for cosmic inspiration. He later said “I missed out on rock, all my influences were French”. These “influences” are most evident in the chanson française style of ‘Brother Gorilla’.

Released in 1972 on the Bantam Cock album, Jake translated ‘Le Gorille’, a song by his idol Georges Brassens, into English. The lyrics spool forth, a rollicking, abstract critique of capital punishment delivered by allusions to a gorilla in captivity. Less direct than the French original, ‘Brother Gorilla’ still identifies the fallibility of judges and state-sanctioned punishment.

‘Le Gorille’ is in the Chanson Français genre, a style with lyrical themes characterised by love, sex, life, and hate. It’s the tradition in which Jake is most readily placed. However, certain elements disturb this categorization. A certain Gallic pronunciation notwithstanding, he usually sang in English about quintessentially English things. Jake also frequently veered into magic realism and fabulism. Often sweeter and more wistful than what Brassens wrote, Jake’s occasional lean towards the ethereal, both musically and lyrically, further distinguishes him from the spiky Chanson style. Jake’s Francophilia was a vital part of his music but he took this influence and translated it, so to speak, into his own brand of Yorkshire chanson.

‘The Bull’ from Jake Thackray And Songs (1981)

Although politics were never directly obvious in Jake Thackray’s lyrics, he had an anarchist streak that manifested as a wariness of authority figures. His song ‘The Bull’ is a dissection of what Joseph Conrad called the “exquisite comedy” of leadership. Here, Jake strikes a conspiratorially advisory tone rather than a didactic one. The lyrics take the particular, a bull on a farm, and make it universal by embodying and interrogating all the character traits of leadership.

“The hero arrives, we hoist him shoulder-high.

He’s good and wise and strong, he’s brave, he’s shy.

And how we have to plead with him, how bashfully he climbs

Up the steps to the microphone – two at a time.”

‘The Bull’ is an antidote to current political discourse in art. There’s Idles’ ‘aren’t they rotten!’ stance, and Spitting Image’s ability to, as Nasrine Malik recently put it brilliantly in an article for The Guardian, “reduce [politicians] to an unthreatening cartoon”. Jake’s Orwell-esque allegory both identifies the absurdity of the whole circus and hints towards the danger. The line “if you must put people on pedestals, wear a big hat” seems particularly appropriate these days.

The self-referential line, “there’s one of them here his name’s on the poster outside”, places himself firmly in the category of a ‘Bull’ and defuses any didacticism by acknowledging his own place in the spotlight, his culpability. Jake warns “Beware of His Honour, His Excellence, His Grace, His Worshipful”. ‘The Bull’ is a song of the times and there’s a lot we can learn from it.

’On Again! On Again!’ from On Again! On Again! (1977)

Jake Thackray was not immune to the type of mundane, everyday sexism that permeated culture, especially comedy, in the 1960s and 70s when he was most active. A noticeable minority of his songs would be rightly held up today as containing sexist lyrics with tired references to ghastly stepmothers and women’s “proportions”.

The most notorious of these is probably ‘On Again! On Again!’ which details the misogynistic stereotype of women talking too much. Jake even prefaced live performances of this track by saying “this song is offensive”. To say Jake was part of a music hall tradition would be anachronistic, but the type of variety sets he played during the most popular section of his career were to crowds appreciative of these type of bawdy songs. It’s obvious Jake wrote ‘On Again! On Again!’ with one eye on the stalls. Tellingly, ‘The Hair Of The Widow Of Bridlington’, Thackray’s song about female sexual independence, is a far rarer inclusion in live sets, live albums, and compilations than ‘On Again! On Again!’.

The degree of irony that Jake introduces by he himself “wittering on again on again”’ in increasingly complicated verbiage does not defuse the sexist subject matter’. There was a glut of major feminist works in 1977, when ‘On Again! On Again!’ was released, such as the first issue of the Women’s Studies In Communications journal, The Women’s Room by Marilyn French, and a report of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights called Sex Bias In The U.S. Code. No matter how tongue in cheek, this type of song was one of the reasons Jake Thackray, something of a dinosaur in an era partly defined by increasing female emancipation, fell out of popularity.

‘Sister Josephine’ from Bantam Cock (1972)

Jake said he once asked himself “What’s funny about being a Catholic?", and realised “it was everything”. Jake’s relationship with the Church was a complicated one. Although he was raised Catholic and clearly found solace in religion, he still railed against authority of any kind. It’s hard to imagine how his priest felt about welcoming an ale-drinking television personality who sang songs about carnal delights into the diocese.

Sister Josephine tells the story of “Big Bad Norman” (or “Bernard” or “Desmond”, depending on which version you hear), a criminal who’s on the run disguised as a nun. It’s one of Jake’s best lyrics, a barrage of virtuoso rhyming and carnivalesque images like ‘sprinting through the suburbs… dressed only in [her] wimple and [her] rosary’. The intricate dual guitar patterns weave with Jake’s voice to create something both languorous and anthemic.

Sister Josephine is the “founder of the convent pontoon team”, the one who leaves “the cloister toilet seat stand upright”, and from whose cell one hears “empty bottles of altar wine come clunking”. You might even draw similarities between Jake and Norman, both having “big” hands, a voice “that’s on the deep side”, and a thirst for booze.

Catholicism stretched throughout Jake’s life. He was raised by Jesuit priests and even considered becoming one himself. However, never was it more important than at the end of his life. At that point, the only performing he allowed himself to do was bellringing on a Sunday morning. Despite this, you get the sense Jake found Catholicism a tight fit and was aware of its manifold peculiarities, hypocrisies, and contradictions.

‘The Black Swan’ from The Last Will And Testament Of Jake Thackray (1967)

The wildly popular South Korean boy band BTS have a song called ‘The Black Swan’ which, according to Wikipedia, refers “to an artist’s fear of losing passion in their art” (thanks, ‘disambiguation’). The parallels to Jake Thackray’s alcoholism and its effect on, or perhaps antidote to, him losing faith in music are stark.

Jake’s songs occasionally make reference to booze problems, such as in ‘Lah-Di-Dah’ where he promises his betrothed to “keep off the pale ale”, but never is this more apparent than in the augury of ‘The Black Swan’. It takes the form of a classic lament with incremental repetition and regular refrains. It’s one of the darkest songs he ever wrote, with soaring string parts wreathed in melancholy and yearning.

“Drink deep, drink long,

Drink our heads off, drink on”

The narrator describes his own damnation, “But don’t come and find me, I’m lost, I’ve lost”. They act as a kind of Jacob Marley figure, “Your life is your own, don’t lose it all”; indeed, Jake too died on Christmas Eve. The traditional English pub setting is made hellish by a strong “we” pronoun, conjuring images of damned souls in hell, “we don’t go home tonight”. Once again, there’s that portrayal of the grotesque and horrific nestled in a comfy, domestic, familiar setting.

Jake Thackray died in 2002, bankrupt and an alcoholic. His unique good looks, all strong jawline, heavy-lidded eyes, and expressive features, became a little more drawn, worried, and jowly. ‘The Black Swan’ offers a mournful glimpse into the life Jake would eventually lead.

Jake’s Scene – Swaledale (1967)

The documentary Jake made for ITN is a fascinating time capsule detailing various, unnamed parts of Swaledale in a liminal state between tradition and modernity. Jake talks to all sorts, such as a shepherd, a schoolteacher, publicans, and old men, having startlingly modern discussions about gentrification, school class size, and the working week.

It’s a charmingly idiosyncratic program. Jake hobbles about on crutches on account of a broken leg and rides on a pony and trap. He plays a traditional Yorkshire game called knurr and spell and sings ‘Old Molly Metcalfe’ at Muker School with the children providing a haunting call-and-response. The old Yorkshire accents are so broad it’s easy to mistake them for Irish or Scottish. ‘Jake’s Scene’ captures a moment right before the Post-Industrial age really started gathering momentum.

Any background information about the documentary has long been consigned to ITN’s vaults so I’m not sure whether this is intentional or not, but Jake seems to inadvertently stumble on replicas of characters and places from his songs. John Tom is similar to the “old men” that “stare at the dead afternoons” in ‘Go Little Swale’. The shepherd on the moors is similar to ‘Old Molly Metcalfe’, especially when he talks about ice forming on his face in the depths of winter. Jake visits a pub called ‘The Black Bull’ and meets a man dressed as a monk for a reenactment (who knows if the ‘Sister Josephine’ parallels were mentioned). The program offers a glimpse of the reality behind Jake’s fantasy of the Dales.

Jake seems to have escaped the booming industry of quadruple vinyl reissues with eight lyric books and a metric pound of stickers. There are no career-spanning interviews or lifetime awards. I hope Damon Albarn never makes a ‘supergroup’ to play his songs but I live in anticipation of a hologram tour of Yorkshire’s flat-roofed pubs. Jake lives on in little snatches of cultural ephemera like this documentary, the odd article he wrote for the Yorkshire Evening Post, a couple of radio programs, and enjoyably lo-fi videos of performances to fifteen people. And I think this is, “more or less”, how he’d like to live on.