Shane MacGowan’s life has been full of surprises so far, and the fact he’s still alive can be regarded as some kind of a miracle. All being well, the Pogues frontman will celebrate 63 birthdays this coming Christmas Day. Even so, perhaps the biggest surprise in Julien Temple’s excellent new film about MacGowan’s life is the appearance of Gerry Adams, long-serving former Sinn Féin president, sitting in his living room asking him questions. Between 1988 and 1994, when the British government brought in tighter measures of censorship for Irish republican and loyalist organisations until the Provisional IRA’s ceasefire, the voice of Adams was banned from British television.

TV networks got around these restrictions by hiring actors to read Adams’ words verbatim in voiceovers, thus causing cognitive dissonance in children seeing the Troubles imported into their living rooms every night via the teatime news. Adams has since rebranded as a more cuddly, avuncular figure with caveats, though his presence in Crock of Gold: A Few Rounds With Shane MacGowan is still jarring whenever he’s on screen. As you might have gathered, Temple doesn’t sidestep MacGowan’s political affiliations, or the revolutionary fervour which drove the Pogues in the early days.

The pair recount their first meeting in a backroom at Filthy McNasty’s pub in North London, ahead of a crunch meeting between Tony Blair and Adams in the mid-90s. MacGowan told him at the time to pass on a message to the British Prime Minister: “Tiocfaidh ar la” or “our day will come”. There’s an awkward dynamic between these two acquaintances with a common objective. Long pauses are occasionally punctuated by MacGowan’s famous laugh, which resembles a serpent clearing its throat. At one point Adams says: “We wouldn’t be anti-British, we just want them to leave us in peace.” Another awkward laugh.

“I’m not anti-British, no,” says MacGowan, staring into space. You can almost see the spiders crawling behind his corneas. More silence ensues. The indecision in MacGowan’s voice is indicative of a conflicted and complicated relationship with the country he was forced to call home, after his parents emigrated from his beloved Tipperary when he was six. Later on, he would win a scholarship to Westminster School but resisted pressures to become an English gentleman. “I didn’t want to be an Irish gentleman either,” he adds, before emitting that laugh again, which also sounds like gas escaping. Perhaps unsurprisingly, after selling barbiturates instead of speed to kids taking their exams, he was expelled.

MacGowan clearly despises British authority, and yet it’s the country where he made his name, and it was in London where his big break came. The Pogues are the voice of the Irish diaspora in the city, and the sound of seditious rebel songs taken from home and given added punk attitude where it was needed. It’s this antipathy for the imperialist oppressors that underpins the film, and sits at the heart of the Pogues’ music.

In his memoir, 2001’s A Drink with Shane MacGowan written with future wife Victoria Mary Clarke, MacGowan said: “I always felt guilty because I didn’t lay down my life for Ireland. I didn’t join up. Not that I would have helped the situation, probably. But I felt ashamed that I didn’t have the guts to join the IRA. And the Pogues was my way of overcoming that guilt. And looking back on it, I think maybe I made the right choice.” It’s an honest admission, but anyone who’s read Rake at the Gates of Hell: Shane MacGowan in Context by Robert Mamrak – a text that goes into detail about MacGowan’s political persuasions and the influence it had on his work – or indeed listened closely to his lyrics, won’t be too surprised.

Crock of Gold does two things very well: it reminds the viewer what incredible talent MacGowan had during the 1980s, and also just how dangerous he was considered by the establishment. In the mid-90s, the tabloid press would cast Oasis as outlaws during the ubiquitous pantomime of Britpop – although they were more a danger to each other than anything else; but a decade earlier the Pogues (formerly Pogue Mahone, Irish Gaelic for “kiss my arse”) already walked the walk, staggering from one incendiary incident to another. They were hell-raisers singing rebel songs about Brendan Behan and Frank Ryan and the rotting corpses from the Great Hunger lying in the ground – and this at the height of the IRA’s bombing campaign on the British mainland.

The Pogues grew out of a band called the New Republicans, who MacGowan formed around 1980 with Spider Stacy and Jem Finer, who’d drape their stage with nationalist flags and play agitational live shows – though as their cult following tipped over into mainstream success, so the marketing team attached to the label went to great efforts to downplay the group’s Irishness. It was a tempestuous time to be from across the Irish Sea, especially after the Tory party conference in Brighton was bombed by the Provisional IRA in 1984. “Writing rebel songs like you did, there was a lot of physical violence. I mean, I remember us getting beaten up,” says Clarke to MacGowan at one point during Crock of Gold. “I wasn’t surprised,” he replies, reflectively. “I’d get the shit kicked out of me and left in the toilet”.

MacGowan clearly wasn’t dwelling on concerns for his own safety when he wrote the second part of the medley ‘Streets of Sorrow / The Birmingham Six’ on the If I Should Fall From Grace With God album. The band played it on Channel 4’s Friday Night Live in February 1988, and the show mysteriously cut to a commercial mid-song. “There were sinister forces at work trying to stop any airplay for this song,” said Frank Murray, the Pogues’ manager at the time. Were lyrics such as “may the whores of the empire lie awake in their beds” deemed inappropriate for a comedy show? This appearance came months before home secretary Douglas Hurd introduced the Anti-Terrorism Act, which, as well as preventing Adams’ timbre from being heard on the news, banned ‘The Birmingham Six’ song outright. Hurd said at the time: “The British public should be prevented from hearing terrorist organisations and their supporters.” Hugh Callaghan, one of the Birmingham Six, later countered: “The last thing the government wanted was people like MacGowan educating the public.” The song also referenced the Guildford Four who were acquitted in 1989 after 15 years of incarceration, with the Birmingham Six released from prison in 1991. MacGowan is still awaiting his apology.

*

Around the time of this controversy, a new version of the Pogues was slowly emerging, or at least a surrogate version that was a figment of the British public’s collective imagination. ‘Fairytale of New York’, in collaboration with the singer Kirsty MacColl (suggested at the last minute by her husband, producer Steve Lilywhite), became the band’s biggest song, reaching no.2 in the UK charts, and with each passing year its mythology has snowballed, seeping into the very fabric of the British Christmas experience. As MacGowan’s creative powers faded, following a tour in New Zealand when he painted himself and his entire hotel room blue (apparently egged on by the spirit of Maoris buried in the ground below), so this other MacGowan began to materialise and take over. His inability to contain this phantasm was compounded by MacGowan’s increasing helplessness from alcoholism, and a punishing overconsumption of acid.

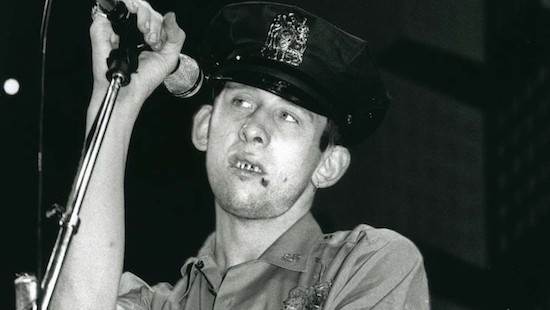

The new MacGowan is a benign Irish caricature crossed with a kind of Christmas elf, swearing at the piano with a cigarette in his mouth. Furthermore, the use of the word “faggot” in the song has unwittingly become battleline in the culture wars. As it flies back up the charts every year, playing on the radio and blaring from the tannoys in shopping centres, that one utterance is an annual cause célèbre indicative of all society’s contemporary ills: it’s either homophobic, careless and offensive; or censoring it is an affront to “free speech”, with little nuance in between. Irrespective of the ‘F’ word, ‘Fairytale of New York’ has become the biggest Christmas song of the 21st century, a chimera that has dwarfed the Shane MacGowan songbook. The English kink for Christmas (as legitimately the most Yuletide obsessed nation on earth) has seen the band’s rebel songs brushed under the carpet with this seasonal grotesquery now fully assimilated into the folklore of the nation. “You want paddy,” he says angrily in the film, “I’ll give you fucking paddy”. For many, MacGowan will forever be the erstwhile parody in black and white being dragged up some steps by Matt Dillon in a cop’s uniform in the video. It’s a far cry from the Tipperary punk who called himself Shane O’Hooligan, scrawled “IRA” on his forehead, and walked the streets unswerving from violent encounters with loyalists and larrikins.

As with Queen’s Freddie Mercury, it’s as if the tabloid media created a whole different character for MacGowan that would fit with the values of Middle England – a necessary step given that these artists had grown too big to ignore. Mercury’s sexuality and ethnicity were never talked about – something he was complicit in – and as Frankie Goes To Hollywood singer Holly Johnson pointed out at the time of his death, the musician was “heterosexualised” by papers like The Sun, with his one ex-girlfriend Mary Austin dragged out as evidence that he’d been misguided somehow and had always been a proper bloke, really. The 2018 biopic Bohemian Rhapsody shamefully riffed on this same perception. Though an Indian Parsi born in Zanzibar who’d made a home for himself in Britain and died of AIDS, Mercury underwent a kind of cultural colonialism, purified and patted on the head, and commended in a deeply patronising way and appropriated as one of ours.

MacGowan’s identity, too, has been stolen, and his true essence denied. He was, and remains, a supporter of 32 County Sovereignty for Ireland – a fact that’s just too unpalatable for some Brits to comprehend or dare to think about. While Crock of Gold probably won’t kill off the rogue, anglicised MacGowan, with his edges filed down and his 7” single slotted in the Christmas jukebox between Cliff Richard and Nat King Cole, it does serve as a reminder of what a remarkable songwriter and performer he was at the peak of his powers, back when the Pogues were the most dangerous band in Britain and Ireland. If ‘Fairytale of New York’ is the Pogues’ own ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’, as MacGowan himself suggests in the film, then let’s hope it’s not one day turned into a terrible hagiography made by profiteers with their own agendas.

Crock of Gold: A Few Rounds With Shane MacGowan will be released in cinemas on December 4 and on DVD & Digital from December 7