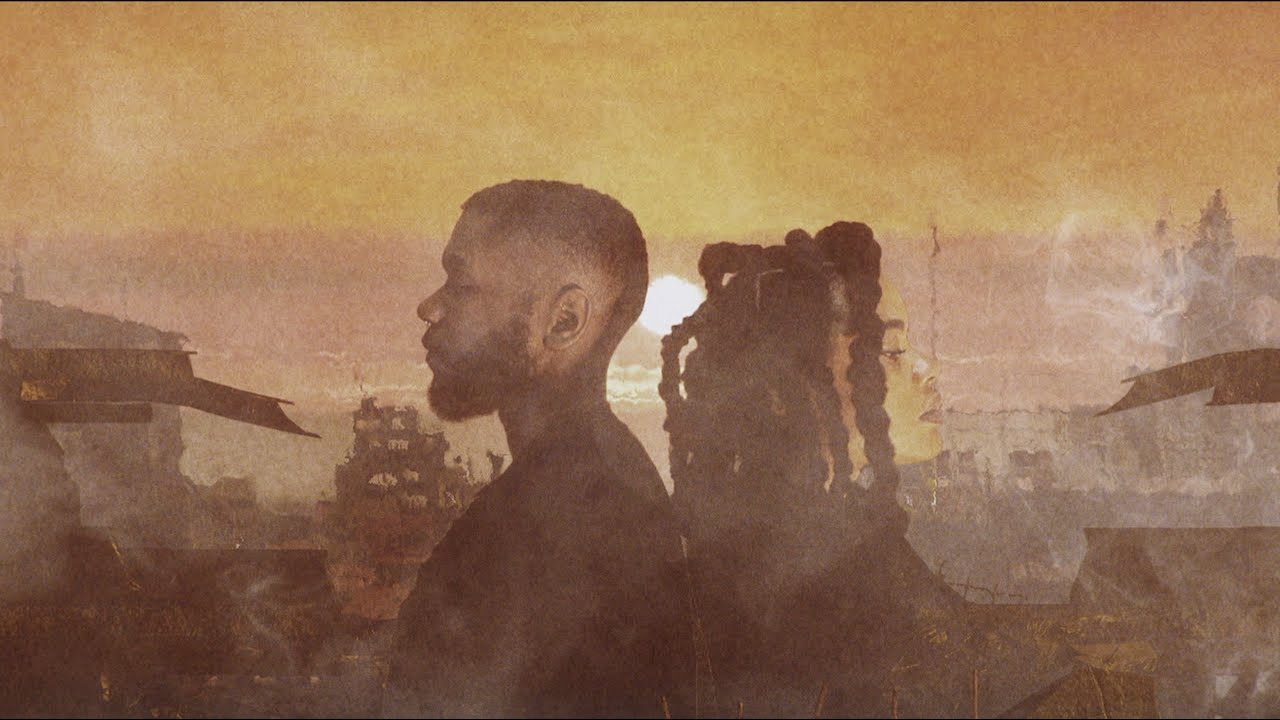

Photos: James Griffiths

As a five year old, Angolan-Belgian artist Nazar spent three months in a huff with his dad. While Nazar was growing up in Belgium with his mother, sisters and half brother, his father was a rebel general back home in the Angolan civil war, part of the anti-colonial movement’s National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA). Nazar’s dark debut album, Guerrilla, which came out on Hyperdub earlier this year, was based on his father’s memoir of that time, Memórias de um Guerrilheiro.

"I remember I was so mad at him. I think I saw him 10 times over 14 years. That time when I was five, h’’d spent two weeks with us, then he had to go back. I told him I’d never talk to him again. For literally months afterwards I wouldn’t come to the phone."

Travel was difficult for Nazar’s dad, Alcides Sakala Simões, now an Angolan politician, who could only travel through countries allied with Angola, such as Germany, to visit his family. He was involved in the bloody power struggle between UNITA and People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) which ran from 1975, following independence from Portugal, until 2002. Nazar was born and raised in safety in Belgium until he was 14, and only heard about the war in Angola through his mum.

"That might be one of the problems I guess, the African way of parenting," says Nazar, who has just finished eating a home-made chicken stir fry and is chatting with me on Skype from his home in Zwolle near Amsterdam, where he lives with girlfriend. "My parents – my dad especially – never truly explained things to me. It was my responsibility to learn and understand. There’s still stuff we don’t talk really about. I have to do all the work. He was keen to give me the coordinates to let me make the map and get a clear picture. Connecting with relatives also helped, and later visiting places ravaged by war over the years."

Guerrilla is partly Nazar’s way of processing that time in his life as well as that conflict, which led to the death of 500,000 people in Angola, with another million displaced. It’s a tense album, scatter-gunned with violence, references to surface to air missiles and arms deals. Helicopters swirl overhead on ‘Bunker’, we hear guns cocking on ‘Diverted’, alongside the swoosh of machetes and flying bullets. But it’s a dance album too, in an itchy, sometimes bright and frantic style, or what Nazar describes as ‘rough kuduro’, his own uglied up hybrid of Angola’s upbeat, fast kuduro dance music, born out of hardship and political instability and played in clubs, house parties and markets. His aggro blend of eerie field recordings, speech, a capella singing and feverish beats are as he puts it, a bridge between two cultures; his European influences and his African heritage.

"Coming from my African perspective, I wanted it to be an album you could move to," says Nazar who grew up listening to kuduro artists like DJ Jesus and Bruno M, the group Os Lambos and the kuduro pop crossover act Eliei. Their styles span abrasive Portuguese-language vocals, rapid, heavy percussive beats, rapping and melodic, more meditative jams, sometimes dripping in melancholy. Later he got into French touch acts like SebastiAn and Justice, as well as fellow Hyperdub artist Burial. "I’ve always listened to electronic music – experimental, underground stuff. It’s possible to try other codes of music to be more widely understood, but [for my album] I stayed true to my own stuff. It’s more gratifying knowing I didn’t compromise."

Nazar was signed to Hyperdub after sending a demo to label founder Steve Goodman, better known as the electronic artist Kode9. The label put out Nazar’s EP Enclave in 2018, which focused on Angola’s violent past and oppression under years of dictatorship.

"People aren’t always aware of what happened in Angola – they might be oblivious to the themes on the album. I like the fact that I have visibility because I’m connected to Hyperdub. I’m a narrator, I’m not trying to glorify what happened, just represent it. Yes, I’d like it to educate too – not in a patronising way, but in a way that doesn’t see the war through the lens of Europe. There is so much ignorance about that time – people weren’t learning about the civil war in schools in Angola, and definitely not in Belgium. I was used to debate in my family, but it was taboo to talk politics in class, they would never raise questions. Nowadays it’s different. Black Lives Matter would have been deemed a terrorist organisation in Angola under the old regime. Pro-democracy movements in Angola were vilified and hijacked."

Nazar remembers one school teacher in Belgium taking the piss when he said his father worked as a diplomat in Angola. "I had this white teacher who didn’t believe me when I told her. She laughed and said, ‘Yeah right! And I suppose your mum is Queen Elizabeth’. Stuff like that filled me with self-hate. I felt extremely lonely. There were a lot of racist incidents which meant that I felt extra disconnected from Belgian society.

"I had black friends but we were in a minority. We had similarities – lots of them were from single mother households too. Most of them were from projects. One of my friends started getting into fights, there was a real gang culture. Not having a father figure, and being a teenager, I was in a weak spot. I felt the need to move to Angola and I think I did it at the right time. It was the best move deciding to go to the Motherland when I was 14." Arriving in Angola for the first time, Nazar began reconnecting with family. "I almost envied my cousins – they had first hand experiences of the airstrikes.

"I would have loved to be there and learn the same life lessons as them. I envy that knowledge. Even if it was dangerous. I can’t ever fully understand what happened. And loads of the most important moments of my life could have been spent with my dad."

Instead of spending time with his father, who was once an enemy of the state, a freedom fighter who joined UNITA with Nazar’s mum aged 14, then moved into the diplomatic, peacemaking arm of the movement in the mid ’80s and eventually earned respect from both sides, Nazar had grown up closer to his mum. "At home mum spoke to me in Portuguese and French. But sometimes if she wanted to say something that I wouldn’t understand, she and my sisters would always spill the tea in Umbundu [the most widely spoken language of Angola]. My mother wanted me to learn the language, but I didn’t want to be associated with it. I wanted to assimilate."

There is a track called ‘Mother’ on Guerilla, the gentlest moment on the album, and Nazar’s chance to pay tribute to the strong female figures in his life. "The women in a conflict are just as important as the men, especially in my family. Because I’ve grown up with three sisters and my mother, and later my auntie and female cousins that I lived with in Manchester, it was the women who gave me more stories. Most of the perspectives I got about Angola were from women. Men don’t really talk about their feelings, how they experience their traumas. I wanted to reinforce that idea with ‘Mother’."

What Nazar learned from his dad, and used as some of the inspiration for the album, was mostly based on military stories about the conflict that he read in his journal. "There are a few passages in his book where it’s a bit introspective, but mostly it describes what happens with an episodic structure. There is a timestamp for each airstrike and location, so I did the same with the album tracks. I wouldn’t have been able to make the album if it was just based on my dad’s stories. I had to do a lot of travelling around the country by road, and hearing stories from lots of other people, that’s what made the album possible."

Although he resented his dad for spending time apart from him when he was young, as Nazar has got older, he’s come to understand the sacrifices that his father made. "My dad could have given up the fight just to have more security with his family in Belgium, but he was loyal to the leader [Jonas Savimbi], a very charismatic and controversial and also scary person who wanted people he could completely trust. My dad never hesitated to do even the tasks that would scare a common person. For example, instead of staying in Belgium as an ambassador, when the leader asked him to go back into the rebellion, at the far southeast of Angola, on the border with Angola and Zambia, the end of the world, my father accepted, and they were the hardest years of his life. He gave it all to fight an authoritarian regime, even if that was at the expense of not being there for his children."

Nazar’s father’s voice is heard on ‘Diverted’ and ‘End Of Guerilla’, reading from his book in Umbundu. "A few years ago I would have had the words translated, but now, the way I see things, I wanted to preserve the authenticity, and I don’t want to put a translation readymade like a microwave meal on a plate. The language can be learned and people who know the language know what it means. Portuguese and English are still put on a pedestal." Just as Nazar has learned more about his dad by studying his book and creating an album around it, he feels his father has got to know him better since the album came out too.

"At school I wasn’t the smartest, it was a bumpy road. My mum did a good job to motivate me when I was young. She also told me a lot of stories about my dad and I wanted to be as smart and knowledgeable as him, to impress him. My dad wanted me to be a politician, an establishment person, a doctor or architect or something, but he came to understand my decision to be an artist. He heard the album and would say stuff like, ‘The song ‘Ceasefire’ is very good, but the bass is too powerful! You need to lower the bass!’"

When Nazar was interviewed by The Guardian in March this year, that seemed to earn more of his father’s respect. "He knows the importance of visibility. He knows The Guardian is very important so that was impressive to him. He has been reading my words in interviews in the last two years. And I’ve been reading his in his book. It’s been an interesting trajectory. He’s come to respect my vision and enjoy my work more, even if he doesn’t truly understand the experimental music I make. He’s 69 and I’m 27 – now there is this exchange of information between us. These interviews help my relationship with my dad!"