The debut feature film from actress and director Caroline Catz is difficult to pin down into a specific form or type, and is all the better for it. It feels exciting to behold a film like this at a time of abundance in music film and documentary, that is so free and boundless and so spiritually in tune with its subject. Delia Derbyshire: The Myths and Legendary Tapes is part biopic, part experimental documentary and part poetic creative dialogue between Derbyshire and latter-day pioneering sound artist Cosey Fanni Tutti, who wrote the score using an archive of 267 tapes recovered from an attic following Derbyshire’s death in 2001 as a sample base. She also appears in the film commenting on Derbyshire’s work and creating music. She features alongside Catz, who plays a version of Derbyshire in visual congress with Tutti, recreating key moments from Derbyshire’s life and work and at times addressing the audience on the other side of the screen. If that is confusing to read, rest assured it’s not confusing to watch. The fluid blend of forms, styles and tones works wonderfully to create layers of time and meaning. If anything, the film’s weakest parts are when it rests into traditional modes. Most of the time, it’s a cinematic fever dream that recalls Charlie Kaufman’s Synecdoche, New York and Peter Strickland’s Berberian Sound Studio – it was interesting to hear Catz mention, in the London Film Festival Q&A where the film received its world premiere, that she approached producer Andy Starke because of his work with Strickland. Most tellingly, the film recalls the groundbreaking late 1960s and early 1970s British television programmes that Derbyshire and her colleagues in the BBC’s Radiophonic Workshop scored and underscored so dramatically. The film is also a bittersweet reminder of the loss of artistry and innovation in mainstream British television craft.

Following a jittery symphonic opening act, the film settles into its rhythm to focus on Derbyshire’s work for the workshop. She was its leading light, responsible for maybe the most iconic theme tune of all time and a truly innovative one – for a certain time travelling doctor – but, as a woman she was subject to routine aggressions and degradations. The film proposes that these nagged away at an already troubled and anxious state of mind. The majority of the film takes place in the same location; a studio containing Tutti working away on her score. This workshop space also houses the sets for the dramatic reconstructions, the sequences that represent different moments of Derbyshire’s life. The effect is to see the studio as a playground, as artistic site rather than technological tool – this connection to Derbyshire’s work stops the film veering into stodgy theatricality. However, it may spend too long here, temporally if not spatially, with the film occasionally lapsing into cliche as it explores the artist’s expansion into addiction, the hippie magnetism of the late 60s and a fractious but passionate relationship with fellow sonic traveller David Vorhaus, before moving back out into the outside world when Derbyshire leaves the workshop in 1973. There’s also a short sequence linking the ubiquitous and probably relevant, but not quite sure why, happenstance of the assassination of John F. Kennedy and its proximity (the day before) to the first airing of the first episode of Doctor Who. This moment doesn’t land at all. It’s one of the film’s few blips. It feels too prosaic, amidst a series of sequences that feel anything but that.

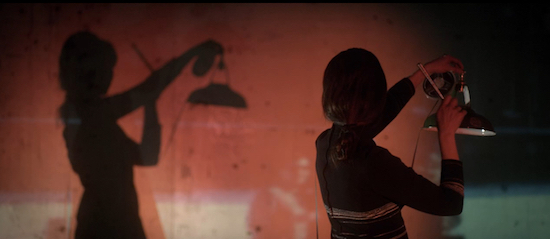

Indeed, the whole section watching Catz as Delia create the iconic theme tune is mesmerising. It’s knowing and self-aware, too, so as not to be pompous while reminding viewers of the inherent collaborative nature of the workshop. The construction of the sequence artfully displays the relationship between banal, pragmatic fragments and the sublime whole of something, where all the pieces are visible but it’s still impossible to work out how they became such an incredible thing. It’s impossible, despite seeing it happen, to work out how it became that. It’s where the film wonderfully captures and communicates that whatever else Derbyshire was in her personal life – she was a genius, only now getting the recognition she deserves. It’s a fantastic debut, and a jolt to the increasingly stale music documentary and biopic landscape, as well as a subtle political account of the battle for electronic music and sound art to be taken seriously. Equally, it’s a sad reminder of the gender battles still being fought in patriarchal workspaces. Stacey Lee’s forthcoming documentary about female DJs, Underplayed, also continues this important work.

This is a beautiful, innovative portrait of a woman in a lineage of pioneering and innovative women, the film directly placing Derbyshire in this line through an imagined dinner with Mary Wollstencraft and Ada Lovelace. The film never dwells on the tragedies, but spends time celebrating and sharing the process and the work, the command of forms and technologies, the art. Maybe it’s telling that what has been hiding in plain sight for so long – the true identity of the artist really responsible for such an iconic piece of music, for a show about a character with the potential for limitless representation and characterisation – has become officially registered in the last few years. Derbyshire’s official credit was issued in 2016, and the first female doctor hit screens in 2018. Both feel more momentous than they probably should in a fair society, but both feel vital to establishing such a society. You can’t be what you can’t see – and this film finally allows Derbyshire to be seen.