Homepage photograph courtesy of John Shepherd

“Imagine if we left behind the strife of Earth, reached Mars and built discotheques there, dancing our nights away in a state of cartoon perfection”, wrote David Stubbs in Mars By 1980: The Story Of Electronic Music. In 25 words, Stubbs mirrors the macrocosmic vision of John Shepherd’s 25-year space odyssey and the celestial soundscape he created for the lifeforms that, just maybe, call Olympus Mons, Eskimo Nebula and Caloris Basin home.

Now the subject of a rightly acclaimed and undeniably touching documentary, which won a Short Film Jury Award at 2020’s Sundance, Shepherd’s story is, in every sense, out of this world. Directed by Matthew Killip, John Was Trying To Contact Aliens covers a vast amount of ground, journeying from the banks of Intermediate Lake in the US to a distance of 500,000 miles into space, all within Killip’s measured edit, which brings the curtain down on this starry-eyed but deeply human tale in little more than 15 mins.

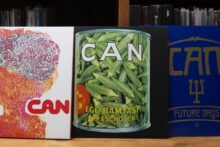

At the age of 21, Shepherd began to build a laboratory of instruments at his grandparents’ home in a bid to communicate with extra-terrestrials. From the early 70s to the late 90s, he used an array of technological kit more suited to a Nasa facility than a nondescript rural Michigan address to broadcast a fittingly galactic soundtrack into deep space. Shepherd transmitted DJ sets featuring Can, Cluster, Kraftwerk, Neu! and Tangerine Dream into orbit, mixing things up with Fela Kuti and Steve Reich, gamelan and jazz.

From a two-storey extension ultimately constructed alongside the family cottage, he deployed a 60,000-volt transmitter to bring Project STRAT (Special Telemetry Research And Tracking) to life, beaming radio shows far beyond the Moon. Killip’s film mines YouTube to unearth footage from Shepherd’s many TV appearances, which find him digging in the crates of a neighbour’s skip for scientific matter, sandwiched between two ufologists on the Joan Rivers Show and dropping the needle on Harmonia’s ‘Watussi’ into a black hole of silence.

"There are no sponsors, no commercials, maybe even no listeners," reports one such news piece, which documents Shepherd devoting the best years of his life to one intangible goal: contact. A self-proclaimed “artist, an explorer”, he is demonstrably both. But, as Killip’s documentary inevitably finds, across these three decades, little, if any, hard data ever materialised.

Killip was originally alerted to the story by a remarkable photo of Shepherd manning a mainframe of homemade tech while his grandma, a few feet away, knits. He admits it’s easy to dismiss the participants of such programmes as being on the Area 51 spectrum. “The dangerous thing about documentaries on people who are interested in UFOs is that it can paint them as eccentric weirdos without going anywhere besides slightly making fun of them. That’s not the kind of film I was interested in making whatsoever,” explains Killip.

Photograph courtesy of John Shepherd

His wonderful documentary is a testament to that artistic intent. It is a story of interstellar dreams sated by the realities of our base existence. A life saved not by music but by humanity. Although now happily Earth-bound, John’s belief in the existence of extra-terrestrial beings remains “absolutely unshakable”, as he tells tQ from his home 250 miles north of Detroit. We asked him to recount this unique journey and also record an exclusive broadcast featuring 10 of the songs that helped to shape Project STRAT.

What are your first memories of this idea taking shape?

John Shepherd: It started to develop over time. First there was an interest in electronics. Then in the mid-60s, there was real interest in UFOs in Ann Arbor, Michigan. I guess it was worldwide but there were quite a few sightings of what Dr. J. Allen Hynek termed “swamp gas”. That whole thing was on the radio in Detroit. I heard a lot of the interviews and it got me really interested.

What TV shows and films sparked this fascination?

JS: I watched sci-fi films and series from as young as I can remember. I saw The Atomic Submarine when it first came out. Then there was The Outer Limits, which was one of the most intriguing and brilliant TV series at the time. Films like The Day The Earth Stood Still. From there, it was a matter of reading other people’s encounters and reports and my own experiences and building and searching, getting the machines set up and running in 1972 and 1973, after I moved from Detroit to Michigan. That’s when it started to happen.

When did you first become interested in electronics? Where did the technology come from?

JS: I started experimenting with electricity and devices around 1965, hooking up coils, bells and lights. I was probably about 12 when I first got excited about electricity and what it could do. I’m self-taught and most of the pieces were built from scratch, [utilising] military surplus, communications material, things I could lay my hands on. I was able to fund it pretty much out of my own pocket and built it over many years. It was a work of love and research. It’s not typical, I know. That’s what makes it so fascinating.

How did you develop the knowledge to build these systems?

JS: The American Radio Relay League (ARRL) had a publication for ham radio. That went into the technical aspects and schematic wiring and explained how resonance works, the formulas. That was one of my resources. In high school, I took an elective in electronics, a basic 101. That was helpful. But a lot of it was hands-on. When you’re working with the equipment and actually getting certain results, you hit the ground running. I could pull a lot of resources and didn’t really have any trouble comprehending it. I was really in tune with that energy and technology.

Photograph courtesy of John Shepherd

How did the musical element emerge?

JS: A really good friend of mine, Mike Johnston, had about 4,000 albums at his parents’ home in Traverse City collected from just about every country. In the same way I was into electronics, he was into music. It was phenomenal. We’d have listening sessions that went on for eight or ten hours. Soon I started to think about transmitting music. My first attempts were binary tone pulses on a small 150-watt transmitter, a vertical marker beacon to try to lure the aliens in. I realised that it was capable of operating at a fairly wide audio frequency range. So I decided to try broadcasting the sounds of the humpback whale. Soon after that I started to broadcast programmes with music.

Why did you decide to use music to communicate with extra-terrestrials?

JS: I felt that music was a sort of universal language and would best suit the open form of communication. It doesn’t need much in the way of translating and most of the music I selected was of the instrumental variety. I felt the more genuine forms of music offered something meaningful. It has to be something that inspires the mind and imagination. That’s when it’s special.

During this period, you’ve admitted “my mind was in space”. Did the rural location and a sense of not belonging compound your obsession?

JS: That’s possible. But I also feel that because I lived in a more isolated place it was quieter and I didn’t have as much activity around me and I had more time to pursue those interests. I don’t know about the loneliness factor. It’s in the film in a way, I admit, but I rarely felt alone. I had my grandparents, they were always around, but it was nice to have Mike and people like that as close friends. That gave me a sense of connection. But the real search was a whole bigger quest for connection with higher intelligence and technology. I was always looking for that next step, that brilliant breakthrough. The possibility of meeting one of these beings someday. I thought if I could learn more about how they operate… wow, it would be a great boom for us all.

The technology became increasingly extraordinary. How did your grandparents respond?

JS: They were real supportive. My grandmother had more interest in the unknown, extra-terrestrial elements. My grandfather was a nuts and bolts kind of guy and taught me how to use all the tools. He was a brilliant machinist. That was where he came in. He passed away some years later and it was just my grandmother and me left. It became obvious that we needed more space. The equipment was starting to take up the living room and parts of the dining room.

In terms of findings, what were the highlights of Project STRAT?

JS: I picked up electromagnetic disturbances on some of my instruments and there were sightings, particularly in 1972 and into the fall of 1973 in the local area and across the US when there was a UFO “flap”. There was that kind of information. It wasn’t hard data where you could analyse it with a spectroscope or a microscope but there was still a reward. There were other sightings and I met with people who had experienced close encounters and spoke with the sheriff’s department.

In the event of making contact, how did you plan to communicate?

JS: It would have depended on the type of contact. Had it been close physical contact, where you could verbally communicate or telepathically, it would probably be like talking to you. Perhaps they would be versed in our language or have the technology where they could project an image outside their vessel.

How did you finance Project STRAT?

JS: I did a lot of odd jobs and after my grandmother passed I rented out rooms in the house to support the work. You had to budget and plan very carefully. Much of the equipment was already up and running so it was mainly paying the bills. But in 1998, I couldn’t find any finance. I searched and searched for people to try and help me but to no avail.

It must have been a sad day when you had to switch everything off.

JS: I was deeply saddened. But I also knew the reality at the time and the economics. If it had been well funded or backed I would have kept it going and maybe refined it, used more advanced technology. Now, it feels like taking a breather, a time to evaluate the search and regroup. With the internet, anything is possible and you can do so much online that you couldn’t even begin to do with all the instruments I had.

You met your partner, John Litrenta, in 1993. How did he react to the laboratory?

JS: When he first came into the house, he took it quite well. He didn’t panic or freak out. He knew quite a bit already but to see his reaction while it was running was a special experience. Even for me it was inspiring to see it powered up and all the energy going through it. I think he saw the qualities in my work and my life and that I wasn’t directionless and had something going for me.

Your story has been retold in John Was Trying To Contact Aliens, directed by Matthew Killip.

JS: Matt had a good vision, which I think matured beautifully. He picked out an interesting angle that no one had looked to do before. Bringing two distinct elements of someone having a life’s pursuit and not necessarily getting those results and then meeting someone, finding contact right here on Earth.

How did you feel after seeing the film?

JS: It brought tears to my eyes. The amazing part for me was that he managed to bring this whole life story into 16 mins and it’s the dichotomy of the two worlds that come together in a beautiful way towards the end. That final outcome. He’s a visionary filmmaker and has a way of approaching films from a very human level that touches the soul. Of course, that was the whole idea of sending music into space. To try and reach out in a human way.

Photograph courtesy of Matthew Killip

Earth Station One exclusive radio show: John Shepherd’s track-by-track

Michael Stearns – ‘In The Beginning’

JS: It’s too bad this track isn’t called In The New Beginning because I see this mix as the start of a new effort to create and share music. Maybe by launching something musically based, perhaps a podcast, to share ideas with a larger community of Earth beings rather than in outer space.

Mark Dwane – ‘Angels Aliens & Archetypes’

JS: This was an important song for me because I knew the artist was highly influenced by the monuments of Mars. Richard Hoagland’s book about the ancient ruins on Mars really intrigued me. When I heard this music based on those visions and impressions, I knew it had to be part of my broadcasts.

Paul Avgerinos – ‘One Path Revealed’

JS: I was heavily influenced by US ambient synth music in the 70s, 80s and still am. This is the sort of material I was broadcasting the most, especially for a space music programme. I’d introduce the show: “This is Project STRAT Earth Station One. Coming up now we have some music from space and music to go to space”.

K. Leimer – ‘All Sad Days’

JS: This is in the film and was actually chosen by Matt. He was very influenced by the German electronic acts like Cluster, Neu! and Harmonia. He saw one of my interviews where I played Harmonia and was amazed. I think Matt thought this would integrate well with the individual snapshots and stills at the start of the film and it does. He’s a great editor.

David Helpling – ‘Free Dive’

JS: There’s talk of underwater bases and that aliens may have built bases underground and underwater and that really rings a bell in my mind, there’s a connection. So it fits in here. First and foremost, I need to love what I’m listening to and if it has that spirit and energy, I’ll use it in a programme.

Brian Eno – ‘Under Stars’

JS: Soundtrack music has influenced me a lot. Also, the connection with the Apollo missions, all of those wonderful space programmes from the 60s were a powerful influence on me growing up. That man was finally leaving the planet and going to the Moon and out into space. Exploration is the key. Exploration is the magic. Whether you’re exploring music or the sea or space.

Cluster – ‘Fur Die Katz’

JS: This mix is almost in two halves. One is more electronic and the other more progressive German rock and electronic, more upbeat and higher energy. They work together, although there is a contrast, because they have the same roots, the same magic in creating music and expression.

Can – ‘Moonshake’

JS: There was so much happening with the German “dream school” artists. I was intrigued by the creative ingenuity of the musicians and the uniqueness of the sound and ideas. Some of it was very experimental. It’s able to shift your brain cells in a new direction, like a coded message, the abstraction brings out a whole different way of seeing things.

Neu! – ‘Hallogallo’

JS: Most of my shows featured longer material, many pieces were 10 mins and up to 30. I like the longer, more contemplative pieces, whether it’s rock, space music, jazz. The more you can be absorbed by music, the more you can get from it.

Kraftwerk – ‘Franz Schubert’

JS: I thought this was a really fitting selection for the mix. It has classical influences and I can also let it roll into ‘Endless Endless’ to complete the recording. That in itself contains a beautiful message.