On a September evening in 1988, the thirty-five year old Neil Tennant braced himself. He’d received some bad news. “That’s that then,” he remembered thinking, “it’s all over.” The cause of such anxiety? ‘Domino Dancing’, the new Pet Shop Boys single – an ambitious fusion of the new Latin freestyle with disco and electronic pop – had entered the charts at number nine. From his years as a journalist for Smash Hits, Tennant knew exactly what it meant when a lead single from an album entered the charts at number nine. But what to do about it?

Reflecting on the two or three years preceding that moment, whilst promoting a series of CD reissues in the early 2000s, he showed that he had lost little of his eye for observation and categorisation. “I felt at this time" he said, “that we had the secret of contemporary pop music, that we knew what was required. We entered our imperial phase.”

Behaviour, which turns 30 this month, would be Pet Shop Boys’ first artistic statement in the awareness that all they touched no longer turned to gold discs. To be sure, Behaviour was critically praised, but critics aren’t always the first to spot the end of imperial phases. It would sell worse than the three previous Pet Shop Boys records. The band’s biographer, the journalist Chris Heath, wrote that in the aftermath of Behaviour, Tennant and Chris Lowe were “battling with, and dismissing, an unusual level of self-doubt.”

Though the singles ‘Being Boring’, ‘Jealousy’ and ‘So Hard’ are amongst Pet Shop Boys’ most loved, the pair have done little to shake the perception that Behaviour was a terse moment in their career, that it had marked the end of the affair. Those singles aside, almost none of its tracks have been performed live since that album’s tour. In interviews immediately following Behaviour’s release, Tennant was already talking about a swift overhaul of their image and sound – which would come to pass with 1993’s ultra successful Very.

This sad, strange album – almost always accompanied with obligatory description ‘autumnal’ – may lack the immediate, fizzy thrill of its three imperial predecessors, but make no mistake, Behaviour is every bit as accomplished and engaging. Perhaps more so. It’s denser, the questions it asks – about friendship, loss (particularly loss), trauma and the passage of time – are larger. Their creative instincts were at their most refined. Plant down the flag, here marks the summit.

Harold Faltermeyer could have been engineered by Neil Tennant and Chris Lowe in a lab. A child prodigy born in post-war Munich, the young Faltermeyer had perfect pitch, and would be classically trained. By his early twenties, he was engineering orchestral sessions for the prestigious classical label Deutsche Grammophon, before going west to work in LA for Giorgio Moroder, during the Italian producer’s own imperial phase. When Neil Tennant phoned Faltemeryer out of the blue, his first question was, “Do you still have the old gear?” He gave the right answer, and got the job to co-produce what would become Behaviour.

Tennant and Lowe had spent a few weeks in 1989 holed up in Glasgow, writing to follow up their Introspective album – the one whose first single had been ‘Domino Dancing’, and had meant to call time on their imperial phase, but actually remains their global best-selling record to date. The material they wrote was proving surprising – not least to themselves. Writing mainly on the guitar, rather than at the keyboard, these sessions produced tracks with an unusually mournful quality. Chris Lowe had never managed to produce a sound so euphoric that Tennant couldn’t temper it with resigned melancholia, but it was clear that for the next record they would have to paint in different, moodier colours. If their last album was called Introspective, their next album would actually be it.

Why the sadder songs? “Throughout all of those years” explained Tennant in a 2018 interview with Michael Bracewell, “I was in St Mary’s Paddington, visiting this good friend of mine who was just dying. It was impossible for that not to go into the songs.” That friend, Christopher Dowell, had grown up with Tennant in Newcastle. They had attended teenage parties together, with aspirational invitations that quoted F. Scott Fitzgerald’s wife Zelda – “She refused to be bored chiefly because she wasn’t boring.” They even formed a short-lived folk rock group together, Dust.

For these young men, and countless others, it was their fate to come of age as the imagined heaven of gay liberation became an all too real hell. Strange lesions and even dementia in men as young as twenty. Unusual colds that would take hold and prove fatal within weeks. Watch them all fall down. Dowell would be diagnosed with HIV, that diagnosis directly inspiring Pet Shop Boys’ 1987 bitter torch song ‘It Couldn’t Happen Here’ and his funeral in 1989 was recounted in the b-side Your ‘Funny Uncle’. How do you balance the pain of losing friends, of being a gay man at the height of the AIDS epidemic, with being a pop star at the peak of your powers? The track that opens Behaviour, ‘Being Boring’, is one answer.

Show me your Beatles, show me your Bowie, and I will show you ‘Being Boring’. A masterpiece, to be sure, but also something more elusive than that. Entering the charts at 36, ‘Being Boring’ eventually climbed to 20, but its legacy wouldn’t be measured in chart success. It became, for many, a song of a lifetime, and for a generation of LGBT people an essential and early monument to a senseless tragedy.

It’s the first track on the album, and it begins on a red herring – ominous synths and unsure bassline wobbling over James Brown’s ‘Funky Drummer’ loop (last seen in the charts the previous year for the Stone Roses’ ‘Fools Gold’) before salvation arrives in the form of ‘the chord change.’

“If you ever want to write a classic pop song use these chords” explained Tennant to Q magazine in 1993, "A flat, B flat, G minor 7th, C minor. That’s The Chord Change. You can’t go wrong with that. A guaranteed worldwide hit.” The chord change had been cribbed from Stock, Aitken and Waterman’s Rick Astley hit ‘Never Gonna Give You Up’, and this high calorie chart pop influence (nothing wrong with that, of course) would be by sent out in heels and make-up by Chris Lowe and Harold Faltermeyer’s stately and elegant arrangement. The raised eyebrow that you can sometimes hear in Tennant’s vocal is entirely absent – he sounds close, as though confiding to you in hushed tones at a crowded party.

The track’s impressive vocabulary (cache, trepidation, haversack) belies a simply structured lyric – a three act drama that begins with Dowell and Tennant’s childhood, takes in their move to London and ends, as Tennant explained to the Guardian, “looking back at what’s happening, and I’m doing what I’m doing, and he’s dead”. Of course, part of the song’s enduring hold is its resonances well beyond gay life. It looks at the biggest of themes – friendship, loss, the passage of time. Anyone who’s life has involved some degree of escape, some degree of self-actualisation can’t fail to be grabbed a little too tightly by lines such as “I never dreamt that I would get to be/ The creature that I always meant to be.”

“If gay people have lost friends" explained George Michael when he picked the track for his 2007 Desert Island Discs appearance, “they do want to hear those people referred to, and remembered and honoured.” This is exactly what ‘Being Boring’ achieved. There wasn’t yet a precedent in mainstream pop for writing that was open and exact about the AIDS epidemic and those left behind, those who – in Allan Hollinghurst’s memorable term – were lucky, and then were careful. Imperial phases come and go, but ‘Being Boring’ holds the real secret to what the best pop can do. It allows people to hear themselves, and to see their lives reflected back at them, which they deserve.

Behaviour would still be, in parts, a dance album, but it’s adopting a different type of dance music than Tennant and Lowe had previously utilised. “I felt like I was missing out on so much that was happening in England” reflected Chris Lowe in 2001 of the album’s recording, “it was possibly the most exciting time in English culture ever, including the Sixties, and we were in Munich.” Instead, this distance probably did Lowe a favour. Introspective had consummated Pet Shop Boys’ relationship with dance music – bringing in Frankie Knuckles to mix one track, and covering Sterling Void’s remarkably utopian (if, now, a little silly) ‘It’s Alright’. It would have been easy to further this on Behaviour, but instead Lowe offers an interesting counterpoint to the prevailing acid mood, looking to deep house and indeed anticipating much of where house music would go to in the 1990s. This means jazzier, more complex chord sequences, greater use of reverb, and softer synth pads – it sounds like the work Larry Heard was doing at the time, parts of Behaviour sound like records by St Germain and Ron Trent that would come a few years later. Tracks like ‘Only The Wind’ and ‘To Face The Truth’ lean heavily into the more luscious end of 70s disco and soul; the latter track being a kind of flipside of ‘So Hard’, unfaithfulness presented not as satire but as tragedy, delivered with gorgeous blue-eyed sincerity. All Pet Shop Boys albums are, of course, set late at night – but Behaviour is much less a tantalising night at the club and far more a dark night of the soul. Late night solitude is the setting for many of the tracks ("In dead of night/ where strangers roam"), and it’s exactly how the album should be listened to.

Nowhere is that deep house sophistication better exemplified than on ‘My October Symphony’ – one of the high points of the entire Tennant and Lowe back catalogue. Taking in ideas from far outside pop, whilst never sounding pretentious, the pair are in symbiosis at the peak of their powers. As well as featuring the visionary international chamber group Balanescu String Quartet, there’s a terrific liquid blue funk guitar line from Johnny Marr – if you want to know why he left the Smiths, just listen to that. (Live, with Derek Green on lead vocals, the track works perhaps even better than with Tennant’s clipped resignation.)

Eternally fascinated by what he terms ‘the beauty and the cruelty’ of the Soviet Union, that Communism was collapsing would have inevitably fed into Neil Tennant’s writing at the time. The primary inspiration for ‘My October Symphony’ came from the recently released biography The New Shostakovich, the former NME staffer and Beatles scholar Ian MacDonald’s groundbreaking study of the Soviet composer, and the accommodations he had made with the constantly changing demands of Stalanism. It’s from this vantage point that Tennant writes ‘My October Symphony’ – but almost all of the questions he’s asking are pertinent to gay life at the turn of 1990. What do we do when revolutions bring disappointment (“We’ve been thinking how October’s let us down”), how do we commemorate (“Mourn the war-torn dead?”), and what becomes of an uncertain future – the song’s central question, “Shall I revise or rewrite my October symphony?” We must, sniffs Tennant at one point, be very brave.

How does trauma work? How does grief work? It’s an affliction of distraction – you’re thinking about one thing but the pain is never far from the surface. To borrow a phrase, it’s always on your mind. Behaviour feels like this at points – Tennant’s writing about one thing, but questions of grief and of loss seep through endlessly. Just look a this verse from ‘Only The Wind’ – ostensibly a song Tennant describes as being about domestic violence, and yet:

"It’s only the wind, they say it’s getting worse

The trouble that it brings haunts us like a curse

My nerves are all jangled, but I’m pulling through

I hope I can handle what I have to do

"

That track – as well as startlingly gothic ‘This Must Be the Place I’ve Waited Years to Leave’ – featured string arrangements by Angelo Badalamenti, brought in by Tennant and Lowe following his work with David Lynch (British audiences could buy Behaviour on the Friday, and watch the first UK transmission of Twin Peaks that same Saturday.)

Considering imperial phases, if you’re to sit and listen to each Pet Shop Boys single in chronological order, the first inclination that the imperial phase is over would probably be ‘How Can You Expect To Be Taken Seriously?’. It’s great, but it’s not single material – not really. There’s little more pop star behaviour than scolding other pop stars, and one wonders whether Tennant was missing music writing – the track is essentially a savage op-ed against creeping moralism and campaigning in pop music, at its post-Live Aid zenith. That it was released with a U2 cover as a double A-side makes its target pretty obvious, but rest assured any hatchets would be buried later that decade when Tennant and Bono finally met at Elton John’s swimming pool – phew! Much better, though, would have been ‘Miserablism’ – curiously vetoed from the final tracklisting at the last minute, it’s a much more effective bit of satire, almost certainly aimed at Morrissey (as had been Tennant’s co-written lyrics on ‘Getting Away With It’ by Electronic, released the year before Behaviour.)

‘So Hard’ became the album’s first single purely by dent of it being finished first, though Lowe would later observe that it probably should have been left off the record. I can understand why – it’s one of their finest songs, but it’s everything Behaviour isn’t. It’s the only out and out pingers moment coming as a reprieve on an otherwise melancholy album, but it does complicate the cohesion. All the same, it’s probably the best production job Faltermeyer did with Pet Shop Boys – a bridge between his classic Moroder work and the new 1990s, packed with gorgeous, airy sonic flourishes that unfold on repeat listens. Even better, it was promoted with not just a KLF remix but Pet Shop Boys shorts emblazoned with the tag “SO HARD”.

Two very early tracks would also be repurposed for Behaviour – the excellent closing track ‘Jealousy’ was one of the first tracks Tennant and Lowe wrote together, whilst the lyrics to ‘Nervously’ originate from 1980. Full of gorgeous lyrical flourishes, and set against a jittery, nerves in the stomach synth line, it’s some of his very best writing on masculinity and falling in love. "I never thought I could tremble as much as this" Tennant whispers at one point, whilst "Right from the start/ I approved of you" may be the high water mark of Tennant’s crisply ironed, RP romanticism.

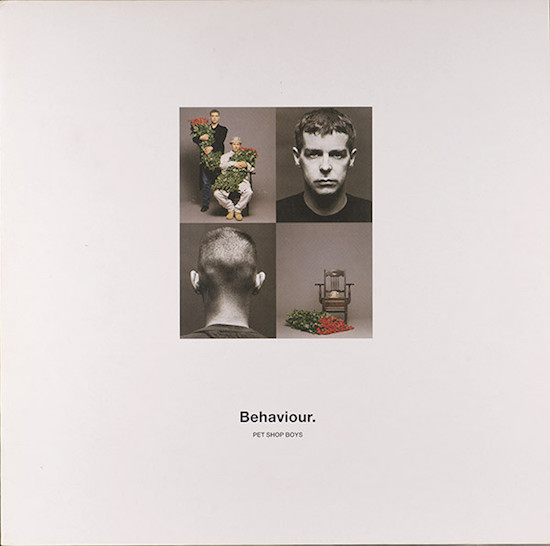

When the album was released, Tennant seemed more – not less – testy about Pet Shop Boys’ position in pop, even indulging in a bit of self-loathing. “I think we communicate a kind of arrogance” observed Tennant to Q magazine shortly after Behaviour’s release. “You sometimes see my face on a record sleeve or a poster, and it’s just saying, aren’t we clever everyone? … You just want to write ’oh, fuck off’ across it, don’t you?” The album’s imagery and music videos seemed to replace their previous irony with a seriousness, something that sat even less easily with Tennant by this point. Behaviour was a nice place to visit, but you wouldn’t want to live there – though they would make mid-tempo, reflective albums again, they’d never really return to an emotional place anywhere like on Behaviour. Never again – after Behaviour, Pet Shop Boys would get on with the work of what it really means to end your imperial phase: use a radical image rebrand to mask a sonic retreat into a settled classic sound, and repeat ad nauseum, changing the formula only by increments. 1993’s Very (a record I love) would do all of these things (and indeed, Very is no less haunted by AIDS neither), but it’s on Behaviour that Pet Shop Boys made their masterpiece, a gorgeous and fascinating document of not just its songwriters in a state of existential crisis, but its entire world order. The end of history? Try telling that to a gay man in 1990.