Online shared noticeboard for Time(un)line Workshop: Mapping the Crisis, a workshop by The Alternative School of Economics (Ruth Beale & Amy Feneck)

As we went into lockdown in March, our access and engagement with exhibitions and events radically shifted as projects entered into temporary closure. Biennials and Art Fairs moved into the next calendar year, gallery programmes transformed into online platforms, private viewing rooms, video screenings, with meetings and discussions held via online platforms. A reality collapse event occurred within the arts, as our experience of the everyday tilted on its axis.

For The Alternative School Of Economics (artists Ruth Beale and Amy Feneck), the cultural changes that have happened during lockdown have opened the potential for new perspectives on the world. These considerations inform their residency for Arts Catalyst The End Of The Present. The project, running from July to December 2020, explores the interdependencies of financial structures, global events, the mass of the universe and time itself through parallel research and a programme of conversations.

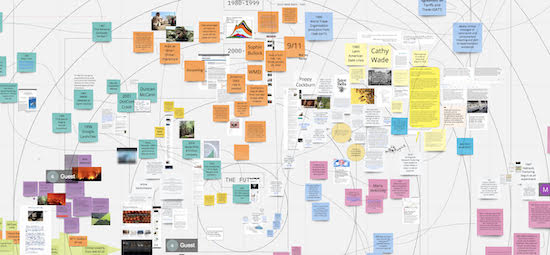

The online workshop TIME(UN)LINE: MAPPING CRISES asked those attending to map through individual and joint research the cause, effects, and entanglements of long global economic crises. The pandemic conditions of Covid 19 frame the workshop. Together we move from a group call to breakout groups within which we mutually support each other’s research into a global event. We share a common online whiteboard, where we all place

our research. The whiteboard contains a series of concentric circles demarcating different eras: the pre-fifteenth century, the 16th to the 18th centuries, through to the decades of the recent past and the near future. Across these zones of time, research into meat production takes place in real-time alongside the Dotcom crash, the 1973 OPEC Oil Crisis, the development of fracking, the Age of Enlightenment, the New Deal Programme of 1933 and the mining of coal in China in 3490 BC. As we search for information, we hear our collaborators typing, shifting on their seats and moving items on their desks. Our group makes a mutual decision to take a tea break, one action we can do together to acknowledge each other’s efforts. In leaving the room to make a drink, suddenly we are alone, the space for informal conversation replaced with a domestic environment and our thoughts.

The workshop manifests itself in ways that mirror the contemporary workspaces that we now operate within. Lockdown has evaporated our work into the home, our daily labour engaged via meetings on laptop screens which hold backdrops of other rooms, bookshelves and fleeting glimpses of cohabitees, children and pets. The oddity of lockdown blurring together leisure and production. The media that occupy the home are now present through the working day. In the spring, the adverts appearing on television fell out of step with everyday lives and the recordings of birdsong dominating radio broadcasts. Newscasters cut their own hair while in Bristol the statue of slave trader Edward Colston toppled, creating a space for the public imagination. Yale University ceased teaching its introductory survey course in art history, citing an impossibility to cover a field of global cultural knowledge adequately.

This news consumed in homes, parks and gardens spaces in which the quality of air took on a noticeable difference as commuters stopped commuting.

The research I undertook for the timeline focussed on the Latin American debt crisis of the 1980s. The initial Google searches lead to a slew of articles on money centre banks and reports from the International Monetary Fund identifying the need to privatise public enterprise and deregulate national banking. These reports felt like the advice given to any bad debtor, that fiscal restructuring and planned payments were the only solution to be offered. As this exploration developed so did the relationship with the co-research simultaneously taking place on the whiteboard. Wars, extraction and industrialisation cut through global events, threading connections from one activity to another, echoing from the present back to the past and future.

Occurring in the workspace next to my own was a timeline that explored big tech monopolies and the falling bee population. Weapons of mass destruction and wars, the banning of plastic waste in China. I considered the impact of researching a Latin American crisis in English with a UK IP address and switched to Spanish. At this point dissenting voices started to emerge in the searches. These questions of access were implicit in the workshop: where was our information coming from? How did we judge the validity of the material we used? What sources were available to us for research? Did we have the time available to pick up books, look for peer-reviewed academic journals, navigate paywalls and delve into the range of sources that informed a Wikipedia article? The Alternative School Of Economics asked us to share the access that we had, the timeline a levelling of the playing field, a site in which to consider models of distribution for texts and resources.

Time, histories and information are multi-levelled and contradictory. In July 2009, at the summit of the Americas in Trinidad, Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez presented a copy of The Open Veins of Latin America (Five Centuries of the Pillage of a Continent) to Barack Obama, creating a voracious market for the book on Amazon. Written in 1973 by Eduardo Galeano the text is a touchstone of anti-imperialist and anti-capitalist economic theory and politics. A recording of five centuries of inequity between the global north and south created in the time of the military dictatorships across Latin America. In 2014 Galeano disavowed his book, debating the capacity he then had to understand the subjects he had written about. Through these fluxes, the books exists as an independent entity pulled into the gravitational forces of global events and changing administrations, a witness to action and stasis. Crises are both macro and micro, unfixed across time, connecting laterally as well as literally. A key consideration throughout The End Of The Present is quantum time and the collapse of linear and parallel timelines. The project’s title is a citation from theoretical physicist Carlo Rovelli’s book The Order of Time in which he asserts, “If I observe the microscopic state of things, then the difference between past and future vanishes.”

There was an epiphany point this summer, experienced while casually watching television, when it became clear that advertising had flexed to respond to the present crisis. Smiling celebrities offered solutions for grey roots from their bathrooms, banks offered to resolve our queries from their workers’ homes, and the vertical plane of mobile phone footage accompanied euphoric messages from corporations about us staying safe together remotely.

Conversations on care and home education were slowly replaced with calls to revitalise our city centres along with debates about the impact of the ongoing recession. Shops, barbers, and restaurants were heralded as the forces that will restart the economy, while galleries, universities and libraries stayed closed.

The conveniences in our lives were called into question. Transport for use only as necessary and social isolation in supermarkets. If we consider that the mass of the universe is 85% unseen and dark matter, our sense of assured knowing shrinks. With this are opportunities to reconsider how we utilise the ideas and concepts that inform us. To unlearn, to test boundaries and make new connections between the events and situations that have occurred on this planet. In considering times of crisis, there is a connection to the processes utilised by the generation of artists documented by Lucy Lippard in Six Years: The Dematerialization of the art object from 1966 to 1972. And works that explored behaviours present in legal, scientific, ecological and technological systems as sites for artistic practices, commons that still question how we make art in the roaring 20s of the twenty-first century.

There is a push-pull in this present in which we should seek to find ways of understanding the mechanisms through which economic theories and histories converge and react in response to crises, to understand what else is possible. This flux of subjects and knowledge is hyper-layered and entanglements, bound to nations, land, ideology, language systems, privilege and access. The desire here to stick our fingers in our ears and return to the new normal is manifest.

For the arts, this normality is a return to exhibition and events, while undercutting this is the potential of what we have experienced through the summer. Together we have directly engaged with the meaningful value of remote access, how it can enable connections and conversations to emerge transnationally and in real-time. Making places in which artists and publics can work in coproduction, redefining the commons into contemporary digital lived experience. These events occurring with the rewriting of curriculums to acknowledge histories and experiences that have been systematically excluded. This creates opportunities for the arts to work deftly, to defy falling into the same patterns and cutting and pasting what we know as placeholders in situations in which we are all finding our way.

The Alternative School Of Economics’ programme The End Of The Present works to create a situation in which we can learn and explore together the past, present and future of economics, environmentalism and crisis that silently impact our everyday lives. The project is timely when we find ourselves removed from the moorings of so much we know and open to considerations of what we need to change.

The End of the Present, a residency by The Alternative School of Economics, continues until Sunday 13 December