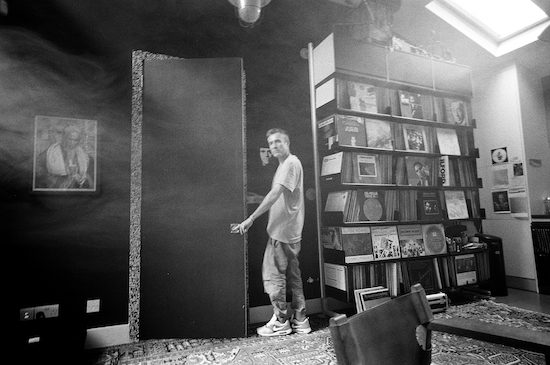

Photo credit: Ed Morris

Liberation Through Hearing, it’s fair to say, is not your traditional music-business memoir. But then, Richard Russell is not your average record-company insider. A DJ and up-by-the-bootstraps artist, he appeared on Top Of The Pops when his early 90s single, ‘The Bouncer’, was a hit of the burgeoning rave era. A love of hip-hop and an immersion in a music scene built on breakbeats took him from north London to New York before landing at the fledgling XL Records, where he went on to mentor The Prodigy as they became the biggest band in the world.

Under his leadership the label discovered, launched and/or energised the careers of artists as sonically diverse yet as culturally influential and commercially successful as Dizzee Rascal, Adele and The White Stripes.

Over the last decade, as a producer and artist, he brought Gil Scott Heron and Bobby Womack back to the studio for records regarded as at least the equal of their earlier classics, and has continued to keep XL and its associated imprints both musically adventurous and profitable.

The book – published on April 3rd, the same day XL released Friday Forever, the second LP by Russell’s ad-hoc collective, Everything Is Recorded – largely eschews salacious stories from behind the scenes, and even its autobiographical elements seem to be used primarily as a structural device. The focus throughout is on the music, the people who make it, and why and how those people and their work succeeded in finding and connecting with an audience – or didn’t.

Even when his own story is, of necessity, pushed into the spotlight, the enduring images are (mainly) ones related to the music rather than the man. Recalling a lengthy spell when he was hospitalised with what was eventually discovered to be Guillain-Barre Syndrome, Russell does not stint on eye-watering detail of his treatment. But the stories that stay with you are of Bobby Womack and Damon Albarn dropping by to visit, the latter with home-made soup.

Most remarkable of all is the plain and unadorned style of writing. Russell has been on a spiritual and philosophical journey, one he carefully avoids overburdening the reader with details of, but which has caused him to analyse and understand his ego so as to both keep it in check, and to be able to channel its effects in ways that are useful to himself and the creative spirits he has chosen to work with. What some may therefore interpret as a curiously detached writing style manages to offer far more erudition and insight than is generally encountered in rock writing. He is tough on himself throughout, yet generous to every reader who comes to the book not prepared just to hear, but to listen.

The brief section where he explains what he concedes was a bizarre decision to release ‘Smack My Bitch Up’ as a single is a masterpiece of concise insight and rhetorical reasoning. In a short paragraph tackling criticism he says XL received for working with an artist as obviously ‘pop’ as Adele, he counters, unbetterably: “The default mode for any artist should be ‘I’m not having it’, and ‘it’ should refer to more or less everything.” Fairly early on, he gives a pithily irreducible thumbnail sketch of the challenges facing creators in our era and explains why he has ended up working with the people he has done:

“Every artist who achieves longevity does so not just through the making of music, but the making of decisions, eventually thousands of decisions, starting with what to call themselves and who to play their demos to, through whether to sack their friend and go with a professional manager, which live agent to work with, and then on to the lifelong navigation of an endless series of suggested compromises,” he writes. “The artists who thrive are not just the most musically talented but the most dedicated to their core values. There is a toughness required for this kind of work, but given that artistry is delicate, a dichotomous nature is necessary. This is the thread that has linked the artists I have worked most closely with. Extraordinary strength coupled with a sensitivity that is so acute it is almost psychic.”

Photo credit: Koury Angelo

The Quietus spoke with Russell via Zoom during lockdown on April 2nd. Excerpts:

The idea of a book was suggested to you, but once you’d decided to commit to it, how did you settle on the voice you’ve adopted?

I just started with the sort of, pour-it-out, stream-of-consciousness thing. Which is good, you know? As a process that’s good – it’s good for you to do that. Then I left it for a bit, and when I looked at it what occurred to me was that, in terms of the voice, I was veering off in two different directions, neither of which was working very well. One of them was a type of gushing enthusiasm – and obviously it was very important that I did capture my enthusiasm, but there was a gushing tone which didn’t read well. And then, completely opposite to that, I would also be sort of drily sarcastic sometimes when I was writing. And neither of these things really worked.

Then there were other parts of it where it felt more relaxed, and I wasn’t using as many words. The sentences were a bit shorter. And I thought, ‘That’s what works’. And also, my editor said to me at a certain point: ‘You don’t need to be afraid of short sentences.’ And I think that was a big breakthrough.

In a way, that journey of working out your strengths and weaknesses in any creative field: it’s a bit like that journey of self-actualisation that you go on as a person. It’s like: What are my weaknesses? Where does my ego come in to play? Because if you can see that you can self-edit, and you can behave in a way which is more constructive, and basically have a better time – and create a better time for the people around you, if you can see the ways in which you are a dickhead. And we all have them! It doesn’t mean they stop, though – it just means you see them so you can moderate them.

That process then – if you like, learning not to be a dickhead, or learning to understand the parts of you that make you a dickhead and how best to work with or around them – is that what you bring to the studio when you’re making and producing music? It sounds, in some respects, like it might be similar: you’re not necessarily reining in the extremes, but you’re acknowledging where the edges of where competence and ability may lie, understanding both strengths and weaknesses so you get the best out of yourself.

I’ve noticed a tendency in myself and others where you can easily think that if you do something complicated it’s good, because you know you found it difficult – whereas in reality the simple stuff we do is often the best. And that can be hard for the individual to see in themselves, because if it came out easily you might not recognise that it’s good – that it’s better than something you’ve laboured over, sometimes.

The singer Fiona Apple, I read an interview with her last week, and she said she’s learned to look out for work she makes where, when she hears it, it sounds embarrassing. If it sounds embarrassing to her, that’s normally a good sign. I think, when we do things musically which are more simple and raw – or imperfect, with mistakes – it can almost feel embarrassing – and that’s a good sign. I think I’ve learned that. Just because you found it easy to make something or do a certain thing, and it was rudimentary and it didn’t involve anything complicated, that doesn’t make it bad – it might actually be what makes it good. So I recognise that in what I do, and I recognise that in what other people do.

An insecure artist will often overcomplicate things. That’s where you get pretentious music coming from. Obviously, there are people who can make complicated things and just make them brilliant. That’s just a different type of thing. I mean, I would say a lot of what Aphex Twin has done is very complicated. It’s technically got a huge amount of craft going into it. And there’s obviously a huge number of musicians whose technical craft is very important to what they do. But it’s kind of combining the clever with the stupid, isn’t it? That’s often where the magic occurs.

So I think, in music-making, for me, one of the reasons I like it so much is it’s like… You know, cleverness won’t really get you very far, and knowledge really won’t get you very far. It’s really about the moment and the vibe in music-making. It’s about the room and the people.

At a certain point when I entered this current phase of music-making for me – which has basically been since I made the record with Gil Scott Heron, so it’s been since 2010 where I’ve been consistently making music and releasing music – and one of the things I realised was that if I was in the room with someone it didn’t make any difference if they were one of the greatest musicians of all time, or if they were someone who’d never been in a studio before, because it’s about what you do on the day. If you’re one of the greatest musicians of all time that might hold you back on that day. And if you’re someone who, this is your first day in a studio and you’re just thrilled to be there and full of energy and excitement, that might be the making of it. Because of that, I’ve got so much respect for people who haven’t done anything before. I don’t over-value experience, and I definitely don’t over-value success. I think those things can definitely hold you back in music-making.

I’m not gonna name who this was, but I went with a young artist to a producer’s studio, and he had all these Grammys on a shelf in the studio. And it’s like: that’s not helping anyone. That’s not helping someone who comes in, who’s a bit nervous. None of that. It doesn’t count for anything. It doesn’t mean anything. Success is just about the past, so it doesn’t mean anything. It’s like, what are you doing now? What are we doing here, together, now?

Clearly, with the book and the album only just out, it seems ridiculous to ask in one sense – but in another, you’ve always been about what’s coming in the future. So what’s next? And how do you keep moving forward while the world’s on lockdown?

I’ve been listening to demos while I’ve been here that Ibeyi have made. They’re an Afro-Cuban duo – I produced their first two records. They really tour – proper like old-school touring – so they’ve been on the road for two years. They’ve just written a bunch of demos for a new record, so we’re just going through that, going back and forth with a view to getting in the studio and working on that. Who knows when that’ll be? For this bit – for them to be writing and me to be listening and giving them feedback – that’s all very, very doable in isolation.

If anything, the quality of concentration you can give to something now, I think, is heightened. I hear people talking about meditating the whole time at the moment, so obviously people are gonna use this time and space in some good ways. Well, you’ve got to, haven’t you? You’ve got to do something good with it, because obviously the negatives are piling up, so you’ve got to make some positives out of it.

So, yeah: I’ll help them with a new record. That’ll be the next thing. But I’ve been quite conscious also of not… We were gonna be doing some live stuff with the Everything Is Recorded record – that’s obviously not happening. We were going to have a party, actually – tonight.

It’s an interesting time to be releasing an album that is conceptualised as a soundtrack to a Friday night out.

It’s Friday night and Saturday morning. I never made a rave album – I only made tunes. So I think this is kind of my rave album. But because I made it now, it’s as much about the aftermath as about the experience. So there’s the anticipation and there’s a fleeting peak moment in it, but a lot of it – the whole second half of the record – is all about the aftermath. And it’s about a kind of loneliness, really – and it’s weirdly sort of prescient, some of it, listening to it now. There’s a song called ‘This World’s Gonna Break Your Heart’. I made the sketch with that sample in it when I came out of hospital seven years ago. And it’s weird that now is the time when that comes out.

Everything finds its time.

I suppose it does. And there’s a lot of unknown aspects to what’s going on at the moment. There’s a reset happening, isn’t there? I had a reset – a personal reset – with the illness, which has ended up being a positive – even though at the time, for the people around me particularly, it was carnage. But it has been good. It’s been productive as a reset. And so now everyone’s got to reset.

Liberation Through Hearing: Rap, Rave & The Rise Of XL Recordings, by Richard Russell, is out now through White Rabbit Books (£20). An audiobook version is also available from Orion Audio, read by Russell and with guest appearances from various contributors including Rick Rubin, Giggs and the late Keith Flint. Everything Is Recorded’s second album, Friday Forever, is out now on XL.