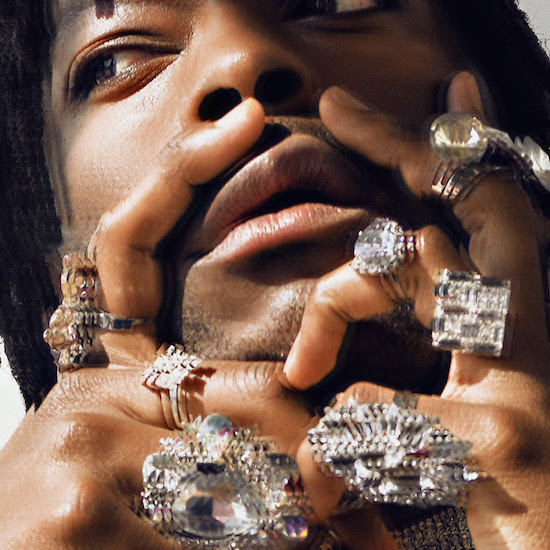

Zebra Katz portrait by Ian Wallman

When Zebra Katz dropped ‘Ima Read’ in 2012, it was undoubtedly an incredible track. Acclaim poured in, as did remixes from Tricky and features from Busta Rhymes. But it was also a weird time. Shows like Rupaul’s Drag Race had just kickstarted a new wave of queer and black gentrification, where memories of masses of white people vogueing suddenly felt even more sinister in hindsight.

For artists like Zebra Katz, Le1f and Mykki Blanco, they were faced with being shoehorned into the neat and quite patronising title of Queer Rap. Zebra Katz naturally concedes that such "visibility is important", but not at the expense of one’s own safety. "I think some of these journalist forget, if I’m playing a show in Russia and someone sees that I’m queer this could be an issue."

It’s been seven years since the stellar mixtape DRKLING and eight since ‘Ima Read’, yet despite what might seem to be an odd lack of new material, this has been a busy time for Zebra Katz, from a collaboration with Gorillaz to a tour with Azealia Banks. This peculiar gap illustrates more the struggle of an independent artist in the modern day, rather than any kind of creative standstill.

What we finally have with debut album Less Is Moor is a vastly developed continuation, but with that key "Zebra Fucking Katz" stamp. The record is a sprawl of beats that bang but also hang in unease. Everything is melancholic, topped with lyrics that balance wit with severity.

TQ speaks to Ojay Morgan, the brain behind the Zebra Katz persona, just as the polite lockdown is beginning, just before the forced shutdown, in Berlin, where he currently resides. It is clear that the coronavirus pandemic is bringing forward a new kind of mutated struggle in an industry that already mistreats its own artists without huge financial backing, something which Morgan is more than keen to discuss.

So, are you in quarantine now?

Zebra Katz: I’m in Berlin right now and the authorities are advising people to stay at home and are encouraging social distancing. But you can’t really make people do anything these days. It’s been interesting that my entire world simply shifted along with everyone else who’s a musician or working creative in this world. We’ve had to cancel the traveling for tours and live shows.

How come there’s been such a gap between ‘Ima Read’ and your debut record?

ZK: Mostly because I’ve been preparing myself to be an independent musician, have a label and to be able to front the cost it takes to put out a release. Previously, I didn’t really know what the process was. I think so many people downplay what goes into releasing a full length release because artists rarely talk about the process. I think you can be privileged and have a label and a bunch of executives that trust in you and believe in your vision and see something that’s profitable, but that doesn’t necessarily translate to me, my work and what I want to do.

I’ve had to take this time to grow from someone who would just release songs for the enjoyment to someone completely different. Those early songs stuck but at that time I did not have my heart set on being a musician when I made them. I quickly adapted to the industry, but I think it took me time to get the funds to build this label and to be confident enough in my own work again to just put it out there and trust that it’ll take care of business.

So you wouldn’t say it’s a confidence struggle at all?

ZK: No, I wouldn’t say I’m struggling with my confidence. This industry is filled with gatekeepers; people that want to commodify you into something so they can profit off of you. I don’t necessarily always agree with that system and I like to work against the grain. The thing people don’t always realise is how difficult it might be for an artist who’s founding their career independently when this entire industry feeds off artists. You might have a team and a manager and a label and an agent and a PR publicist and need to be constantly touring and releasing music just to pay for them. And I think that’s a clarity that most people neglect to speak about. As an independent artist, I’m not afraid of saying that. And if people want to say I’ve struggled in that sense, that’s fine, but it was my choice not to pay $30,000 a year alone for PR.

How do you feel about referencing your earlier work?

ZK: I always reference my earlier work, especially ‘Ima Read’. I think I was really lucky with that song. I have nothing but the utmost respect for it, and I just think it’s really hard to see the impact you’ve had as a musician on people if you’re not constantly engaging in conversations like this. I still think the song is relevant, and I still think that people resonate with it, and it was recently used on Dear White People. It’s nice to see people gravitating to and still being inspired by that song. And that moment, you know, because that moment and video changed my life. So it’s hard for me to look at it any other way.

Could you talk about the name Less Is Moor?

ZK: It’s called or Less Is Moor for multiple reasons. Firstly, it’s a continuation of my earlier work Moor Contradictions, where I first debuted with Zebra Katz. I wanted to reference my work again and create a continuation. It’s also a kind of ode to minimalism. It also plays on disenfranchisement. The fact that you are given less than expected to do more as a young black mother. I’ve always had my sexuality and race projected onto me. And then I was also told that because I knew because I was black and other, I’d have to work twice as hard. So it was kind of my way of dealing with that statement and dealing with those projections in a way that I was owning it.

What message are you trying to get across with the record?

ZK: With my work I really want to reflect the times we live in. I really wanted to reflect what I’ve learned in the last eight years as a musician, as someone who was touring and travelling due to my musicianship. I’ve had a chance to see the world and see how I get treated, and how people project things onto me in order to make themselves feel better. It’s a reflection of what Nina Simone said, it being an artist’s duty to reflect upon where we are living. I wanted to reflect the times we live in which are quite abrasive and quite desperate and dangerous – depending on who you are. When you are a black man in America, or a black trans woman in America, or any black body in America, you’re at the top of the endangered species list. We’re being shot dead in the street by police officers, who then get away with it. That’s fucked up. With this album, I’m dancing with that oppression, that aggression and that rage. James Baldwin said “To be a Negro in this country and to be relatively conscious is to be in a rage almost all the time.” So I am enraged. A lot of people are.

You’re quite outspoken on the issue of queer identity in relation to yourself? How would you describe your stance on that?

ZK: My queer identity is another thing that has been constantly projected on me, especially at the beginning of my career. I always felt that it was me being introduced to a world of people that wouldn’t probably understand where I was coming from if it wasn’t for my sexuality, and I felt that a lot of my work was stronger or had more of an impact when it wasn’t packaged and categorised in such a simple way.

Before ‘Ima Read’ came out people knew nothing about me, knew nothing about my sexuality, knew nothing about ball culture as far as I’m concerned. It was just really interesting to see this happen, and this change happened where we were these select few labelling men of colour ‘queer rap’.

"Queer" is, I think, a term that’s going to be constantly evolving. I thought the term "Queer rap" was fucked up because it was essentially only referring to three men of colour. It was excluding trans women, it was excluding cis women in this meeting, lesbians and someone like Njena Reddd Foxxx for example, who was featured prominently on a ‘Ima Read’. When the media wanted to focus mostly on sexuality, she kind of got written out of that narrative. I thought it was fucked up because her story is valid, and I think the media was just so focused on our sexualities and skin tone that they sexualised the genre of music. It didn’t need to be, hip hop is the only genre of music that’s been sexualised in that way. And I was just there asking ‘Why?’ I didn’t feel right to me, as you had the likes of Frank Ocean come out a few months later. The whole genre separation of queer rap just felt unnecessary to me.

Through my career I’ve been vocal about this. I feel that if I’m in a culture that is accepting of people identifying as they choose, then I should have the same right, and I didn’t feel that I was allowed that right, mostly because of the colour of my skin. So I had a really difficult time speaking about that and trying to find the words to be eloquent and express how I felt when I was doing all these media interviews that solely wanted to focus on my sexuality, with no attention paid to my music, nothing about my accomplishments, nothing about where I’ve been, where I’ve studied, who I’ve worked with. They just wanted to focus on the hardships I would have to face in order to keep on doing what I’m doing. That wasn’t celebrating gay artists and I took issue with them letting people think that that’s what they were doing. So that’s kind of where I stand with it. Am I proud to be who I am? Absolutely! Do I run away and hide from that? Not at all? Did I have an issue with it in the beginning? Absolutely. And I think why music is so sexually charged, especially this album, is because I shied away from it because I didn’t want to be obvious and just make an album about queer sex because that’s all that people wanted to hear about.

I think in 2012 this genre of rap started to open the gate for a lot of other individuals that may or may not have felt that they didn’t fit within the landscape of hip hop music, but queer black people have always been in music and they’ve always influenced mainstream culture. So in popular culture, I thought the name Queer Rap was a kind of a disadvantage to the people that were leading the way and to those who were referred to or defined by their black otherness. You know, I look at someone like Little Richard, who has always been an archetype, a legend to this day. He was extremely flamboyant in a time when they didn’t even have the language to explain or describe or categorise what he was doing. I think about all of his accomplishments. He’s the archetype of rock & roll but will never be credited for that because of the colour of his skin. He was there first and then whitewashed by musicians like Elvis.

Do you feel pigeon-holed by your queerness identity because of idea of ‘queer rap’?

ZK: Whenever someone asks me about this, I’ve already considered my responsibility because this is the life I live. If it wasn’t for my sexuality, it would be my race. So that’s just kind of how I see the situation and, yes, if you’re queer, or if you’re other, or you’re disabled, a majority of people are going to say you’re going to have a hard time doing this, but you can just fight it. Fight against it. I mean, L’il Nas X acts as a prime example. It’s mainly people who are neither queer or of colour calling him a queer rapper. You have a person who apparently lives outside of the confines of the categories being placed on them by people commenting on their work without having any queer theory or black references. When I talk about a lot of people in this industry, their [only] queer black references are like Ru Paul’s Drag Race.

It’s really hard to be a black body, to have to find your own identity, when you’re constantly having stereotypes and labels projected on you. That was my main reaction against it. I just hate that I had to spend so much time fighting against it. I think there are so many other things we can be discussing because I think that ceiling is kind of broken now.