Originality in pop is an overly-fetishised concept, especially by music critics. I have probably caught that bug a little myself, which is why I hadn’t found myself revisiting Elastica’s two albums too often over the past 20 years ago since I first fell in love with them. Yet in this age of refinement I increasingly feel that to dismiss the unoriginal, as many critics so love to do, is an act of over-intellectualisation that ignores the profound visceral aspects to our experience of music – the sexual, sensual, emotional, aesthetic. As the dearly departed Andrew Weatherall told me when it comes to originality, "when pretty much everything has been done you’ll become original by default if you have that slightly amateur approach, and you do something for the love of it and do your approximation. In a nutshell, approximation over originality." Elastica did approximation with more panache than most.

In the eyes of some, Elastica epitomise the many and justified critiques of mid-90s Britpop. The claim that their music was derivative and more about poise than substance has a superficial logic to it – Wire, after all, would have liked to sue the band for the obvious lift of ‘Connection’ from their own ‘Three Girl Rhumba’ – but that reading of their history is a reductive one. So too is the wearily misogynist claim that Frischmann’s then boyfriend Damon Albarn was actually responsible for writing much of their debut album, something that I still hear repeated to this day. In any case, what I loved about Elastica then, and why I still love them today, was that artifice, poise, inauthenticity really didn’t matter. In the mid-90s, they were a fizzing, exuberant breath of fresh air.

Formed by former Suede guitarist Frischmann, Donna Matthews, drummer Justin Welch and bassist Annie Holland, Elastica’s released their eponymous debut album on 13th March 1995. It instantly went to number one in the charts and by the end of the year had sold over a million copies worldwide. It’s not hard to see why – out of any of the guitar records that unexpectedly sailed to the top of the charts over that period, Elastica is riddled with pop hits. Take ‘Blue’, for instance, two minutes twenty-two seconds of flickering, pulsing melodic fizz, vocals layered over the top in exquisite harmony. No wonder serious music fans hated them – this was punk, but with any earnestness boiled away, then distilled for a mainstream, teenage audience.

Take Wire’s ‘Three Girl Rhumba’, in its own right a brilliant exercise in reducing music to a hacksawed minimalism. The canniness in Elastica’s ‘Connection’ is to take that snide austerity and use it for the bare bones of a track that’s all high cheekboned surge and infectious melody carried even by the dirtily grunting boom in the instrumental passages. It’s a song of utterly carefree jouissance, the key to an album that was libidinous in a way that at the time felt entirely unique.

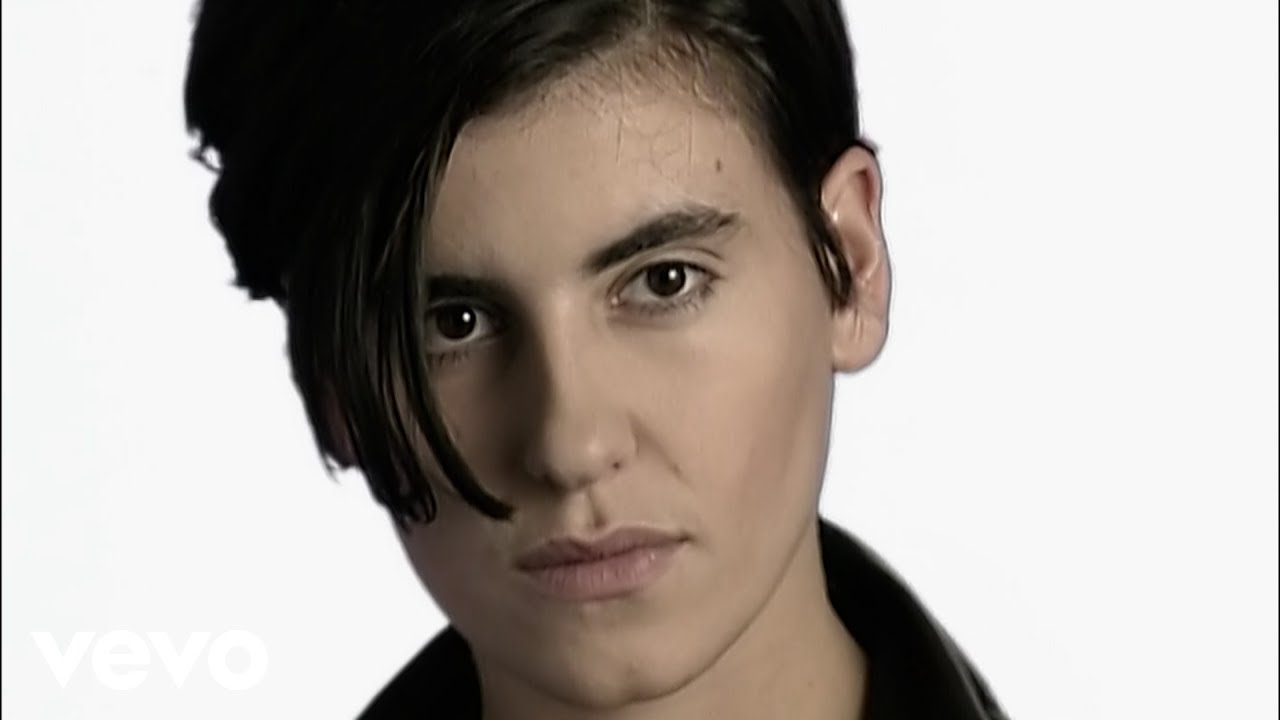

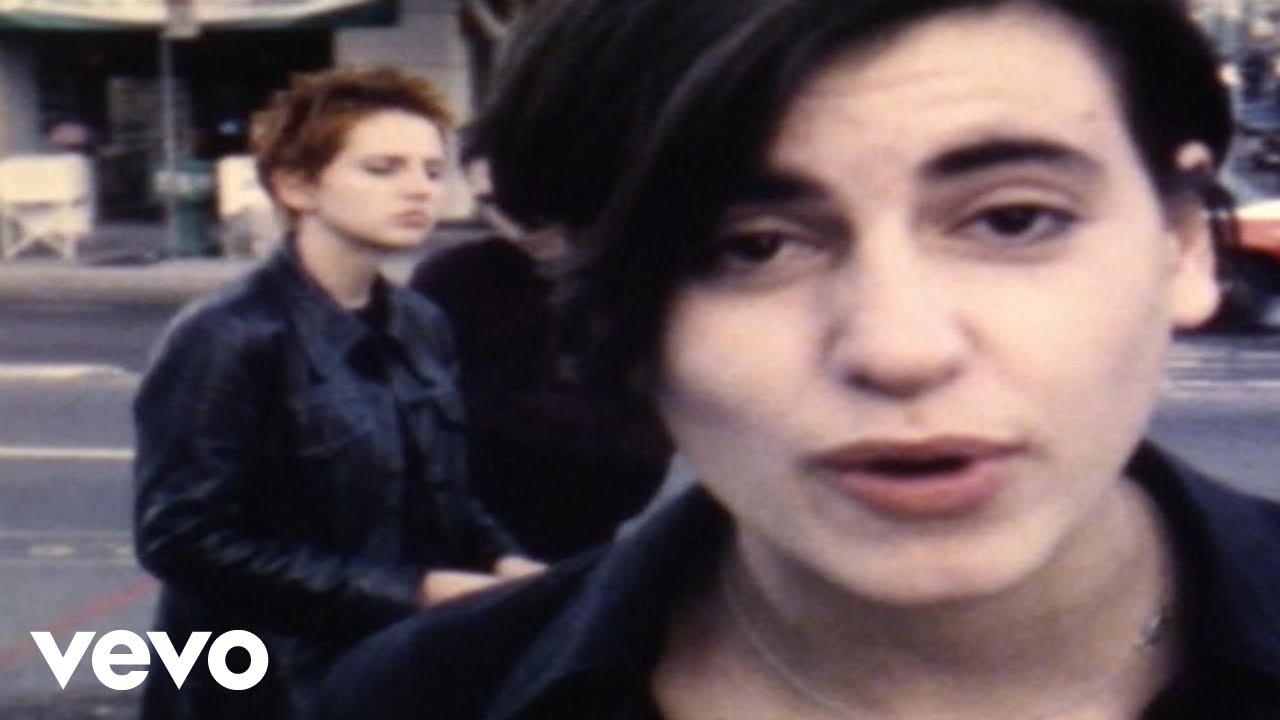

I don’t think it’s possible to overstate just how grimly blokey culture was in the mid-1990s. For those of tQ’s readers who haven’t read my other articles on the matter, here we go again: the media loved Oasis’ cartoonishly boorish antics. Blur had sniffed the wind and followed them into a dull interpretation of provincial masculinity (as Frischmann would later say of Albarn, "I think for Damon it was about becoming a yob. Finding his football friends and becoming quite playful about it. Just starting to assume the character of the insensitive yob and letting that get you through"). Every Friday Chris Evans turned up on TFI Friday to take the piss out of celebs, humiliate his colleagues, and present a dismal train of live sets from bands of lads with guitars. There was the constant air that all the wazzocks were just desperate for post-Take That Robbie Williams to be gay, just so they could take the piss out of him. Against this, Elastica’s insouciant androgyny was a revelation. We had Jarvis Cocker, sure, but he was a sort of weird beacon of hope for the unconventionally attractive male. Suede of course, but for all the blurring of gender in Brett Anderson’s personae, they were still all men. Elastica had something else – I am probably not alone in buying their debut album in a lusty haze for the record sleeve. The Jurgen Teller photographs of three boyish women and a cute twinky lad on the cover and inside the booklet might not look revelatory in an age where gender fluidity is everywhere, but my God they were then.

Yet Elastica’s gender play was quite at odds with what was happening elsewhere in leftfield music at the time, with none of the rage of Huggy Bear, Hole or PJ Harvey. You could argue that ‘Line Up’s tale of a groupie called ‘Drivel Head’ who "knows all the stars / Loves to suck their shining guitars / They’ve all been right up her stairs" isn’t terribly sisterly. Similarly, Frischmann had little time for the Riot Grrrl movement, in a 1994 Vox interview saying that "I went to a couple of gigs and couldn’t make head or tail of it. I just thought, ‘Go home and do something you can do!’ Really, it’s not that hard being a girl in music. In fact, there are lots of advantages to it, and it’s that kind of optimism I’d like to get across rather than moaning about what sex you are." Perhaps this frustration at Riot Grrl’s default amateurism stemmed from the frustration of being a member of Suede in their lean and hopeless pre-fame years –"Apart from anything, I couldn’t deal with being the second guitarist and having this strange, Lady Macbeth role in it, along with being general mother to four blokes," she reflected in 2003. These days the well-off privately-educated daughter of an engineer who worked on London’s Centrepoint tower would no doubt be told to check her privilege for her Riot Grrrl comments (and indeed in later years she largely went back on them).

Instead, it’s when we look to Frischmann’s lyricism that a more interesting, nuanced picture emerges. If most male rock and indie music is the driven by sexual frustration and bitterness, then Elastica exudes a suave confidence. Two of the landmark albums of the period, Suede’s debut and Blur’s heartbroken 13 were written by men about Frischmann. Where Brett Anderson’s lyrics for the likes of ‘Animal Lover’ were the snarl of the wronged party, Albarn’s ‘Tender’ felt like a desperate plea for healing as his relationship with "the ghost I love the most" slipped away. Frischmann’s words on her band’s debut album, on the other hand, displayed no such angst, instead exploring sexuality with explicit wit and a twinkling eye. She is always in control and the men are proving hapless in songs that range from the Viz-like puerile ("when you’re stuck like glue / Vaseline!") to a the recurring theme of erectile dysfunction – the party man who’s kept her "sitting here waiting / yeah, and it’s getting frustrating" in all ‘All Nighter’ to another flopping disappointment in ‘Stutter’ – "And it’s never the time, boy / You’ve had too much wine to stumble up my street". It’s a rather delicious antidote to the braggadocio of Oasis’ "feeling supersonic / drinking gin and tonic". Combined with Elastica’s tight aesthetic (black clothes, DMs, flouncing hair), it was a deeply seductive package for all of us kids trying to work through our sexualities.

While some critics churlishly complained about Elastica‘s lack of originality, it became one of the fasted-selling debut albums in UK chart history. Hundreds of thousands couldn’t give two hoots about how original these songs were – and neither did Elastica themselves, always perfectly frank in interviews about how they enjoyed making music that paid tribute to the artists they loved. Honesty was always part of the appeal. In an age when so many of their peers were taking downwardly-mobile trips in class tourism, Elastica were refreshingly honest about their origins, Frischmann never trying to hide her languid upper-middle-class drawl. You could say it was part of the band’s sonic identity and Elastica were, like many of the best British groups, a complex mix – Frischmann’s family came to the UK as refugees from the Holocaust, and the rest of the band were from working class backgrounds. A pursuit of class authenticity is frequently as reductive as complaints of magpie tendencies in musical creation.

Elastica was a record that almost propelled the foursome to great heights. Pulp, Oasis, Suede and Blur all failed to break America – indeed, it became a bogey country that in the case of Suede and Oasis would break them. Elastica, though, were subject to a frantic record label bidding war in the US that led to them signing a deal with Geffen and flogging half a million records in a year. And then… silence.

While the other bands of the era galumphed around with Tony Blair and played charity football matches for the tabloid media, Elastica had slumped into serious heroin addiction. I remember a rare interview from the time in the music press, half the band sat on a bench on a North London hill, looking hollow and unwell, their conversation fractured and despondent. Reflecting years later, Frischmann said that the pressures of being half of a celebrity couple, incessant touring of their debut album, and fracturing relationships within the band had combined to her becoming a "sad junkie". Annie Holland quit. British guitar music went from tiresome boasting to beige, as the dregs of Britpop gave way to Coldplay and Travis. When Elastica reappeared with The Menace in the year 2000, it was hard to know where they sat. The music press derided them as slackers, the realisation of Frishmann’s promise in ‘Waking Up’: "I work very hard / but I’m lazy / if I can’t be a star I won’t get out of bed".

After years of aborted studio sessions, The Menace was eventually recorded in just six weeks, largely because the band had been asked to play the Reading Festival and needed some songs. The result was an album that, compared to the debut, was awkward and noisy, discordant and odd. As Brett Anderson details in his recent memoir Afternoons With The Blinds Drawn, his rekindled friendship with Justine Frischmann saw her popping round his flat with records by ESG and Faust, enthusing about the joys of drum machines. (Frischmann had also joined Suede onstage at the 1997 Reading Festival to perform ‘Implement Yeah’, a revived ancient Suede song that was a tribute to Mark E Smith). All of this made its mark on The Menace. It didn’t really sound like anything else around at the time, far more upbeat and lively than the noodling mithers of most of the post-rock sadlads and a world apart from any of the dregs of Britpop still doing the rounds. The opening salvo of ‘Mad Dog God Dam’ and ‘Generator’ took the urgency of songs like ‘Line Up’ and muddied them with weirdly honking synths and megaphone hollers. New keyboard player Dave Bush had been in The Fall, and he dragged Mark E Smith out of the pub for ‘How He Wrote Elastica Man’, a lurching, exuberant number that saw the barks of Himself working rather well with Frischmann’s vocal yelps. ‘Your Arse My Place’ took the prowling sexuality that imbued Elastica for a few too many down the pub and stumbled home with it, happy, randy, and drunk. The same goes for ‘Love Like Ours’. Best of all though are the quieter, mid-paced moments. ‘Nothing Stays The Same’ is a disconsolate lullaby, while ‘My Sex’ is all nocturnal heartbreak, gently spoken words like those mantras that keep you awake wondering and wishing what you could have done to change something that of course was inevitable.

I saw Elastica live on The Menace tour, at a Norwich venue a fraction of the size they could have expected to play five years before. For a group that had come through so much, it was a high-energy, sweaty and rather joyous affair, and remains one of the most intensely loud gigs I’ve ever seen. It seemed that it might be a new start for Elastica, but by 2001 they split for good. I’ve always felt this was a shame. Their music fitted in perfectly with the sort of tunes being played at clubs like Trash and, later, Optimo. Around that time there were a host of groups coming through on both sides of the Atlantic who played a very similar discordant take on post punk – Kaito, Mclusky, Ikara Colt, Peaches, early Chromatics, Erase Errata, Liars. Elastica would have fitted in perfectly alongside them, as of course they would alongside one of the finest periods of The Fall’s late career and a revitalised Wire, who released one of their best albums, Send in 2003. Then again, perhaps they didn’t need to. Justine Frischmann was still involved with music, helping to kickstart the musical career of a young filmmaker called Maya Arulpragasam, who you’ll better know as M.I.A.. As detailed in this excellent Pitchfork article, Arulpragasam had already designed the artwork for The Menace and made the video for ‘Mad Dog God Dam’. Frischmann repaid the favour by co-writing M.I.A. breakthrough ‘Galang’.

For me, the joy of Elastica’s two albums is found first and foremost in how well they stand up against anything by most of their peers – the debut, in particular, still sounds like one of the best pop records of the era. Secondly, in their wry, magpie way, Elastica got me into Wire, The Menace solidified a burgeoning love for The Fall. In November 2000, Mark E Smith and the group would release The Unutterable, a record growling with electronic production that, curiously, sits rather nicely alongside Elastica’s second record. I make no claims for Elastica’s originality (the band didn’t themselves, after all), but they were that rare and brilliant thing – a band who are able to distill old, difficult, complex influences into pop, a drug with which to hook teenage minds, and lead them down stranger paths. Originality be damned.