In his text The Weird and the Eerie, Mark Fisher found a profound confluence of the weird with the grotesque in the music of The Fall. Pointing to the group’s work between 1980 and ‘82, Fisher writes: “The group’s methodology at this time is vividly captured in the cover image for the 1980 single, ‘City Hobgoblins’, in which we see an urban environment invaded by ‘emigres from old green glades’; a leering, malevolent cobold looms over a dilapidated tenement.” He continues: “But rather than being smoothly integrated into the photographed scene, the crudely rendered hobgoblin has been etched onto the background. This is a war of worlds, an ontological struggle, a struggle over the means of representation.”

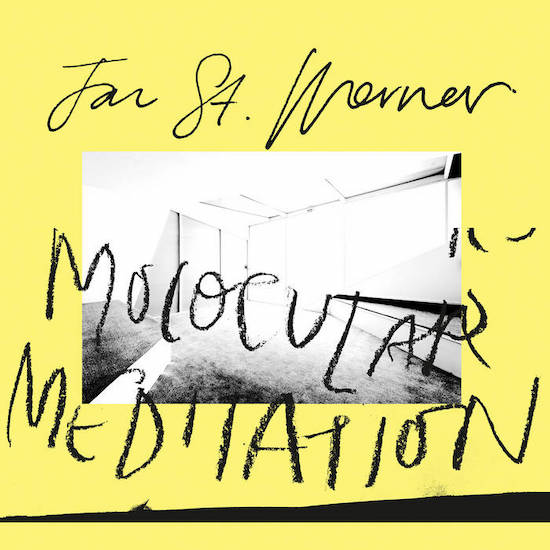

On Mouse on Mars member Jan St. Werner’s new record Molocular Meditation, the ghost of the late Mark E. Smith escapes Hades and materialises in St. Werner’s studio as that hobgoblin on the cover of the ‘City Hobgoblins’ single. Though the album finds St. Werner re-editing a set of songs that were originally recorded in 2014 at the Cornerhouse, Manchester, in the guise of a multi-channel installation (as well as unreleased new material partly written around that same time), it’s nigh impossible to not hear the album as a voodoo ritual calling to Smith beyond the grave, demanding he make his physical presence, his voice, and his words known once more.

On this record, Smith becomes the cobold – a material spirit of Germanic folklore that will typically play tricks if insulted or neglected – that uses the ethereal and alienating nature of St. Werner’s wobbly synths, fractured melodies, and spectral keys to offer his disgusted observations on what humanity looks like to him now as a subterrestrial being.

This, like the cover of ‘City Hobgoblins’ according to Fisher, is a war of worlds and an ontological struggle. Though it’s difficult to imagine Smith as ever truly part of our plane of existence, on Molocular Meditation he’s an invader of reality. It’s almost like St. Werner has rendered Smith as one of the Lovecraft or Arthur Machen characters that Smith so fetishised when he was alive. As in a Lovecraft story, Smith is a force from outside our world and beyond our material understanding gifting us with forbidden knowledge.

The difference? Smith’s ‘forbidden knowledge’ reveals aspects of our world that should be obvious. “Initially it seems like the perfect place. However, they quickly find that their ridiculous goddamn’ lives are caught up. It’s inexplicable,” muses Smith as St. Werner modulates his last syllable into a dropped beat that fades out of concrete reality on the eighteen-minute opening title track.

The album is atypical sonic terrain for both its respective artists. Musically, it shares little in common with St. Werner’s work in Mouse on Mars, which generally trades in lush, spacious, and heady electronic beats, and more in common with producers and musicians that have been associated with hauntology: Philip Jeck, Aseptic Void, and Leyland Kirby’s slightly more beat oriented work as The Stranger. The music is cryptic, otherworldly, and uncanny. The dislocation of Smith’s voice from The Fall is jarring and thrilling at times.

Whereas in The Fall it often sounded like Smith was channeling the ghosts of Stefan Grabiński and Wyndham Lewis through the terrestrial terrain of his band’s distinct working class modernist rock n’ roll hybrid, Molocular Meditation finds Smith himself as the spirit being channeled through the bizarre nature of St. Werner’s production. Though I’m sure the project was worthwhile and interesting on its own when it premiered in 2014, it is true that Smith’s untimely demise in 2018 brings to the fore a level of narrative subtext that the listener can read into. Smith isn’t here anymore, but he is here – in some form or another – on this record.

On second track ‘Back to Animals,’ a muted techno beat propels the intro through the first minute into a breakdown of synth swirls that sounds like AI having a panic attack. Smith’s voice is lower in the mix than in the opening track. “Everything else is slow,” muses Smith before the rumbling bass kicks in and a bricolage of disjointed electronic sounds overwhelm the brain space. This is a synaptically confusing album, and it becomes more gripping with each listen.

On the closing track ‘VS Cancelled’, a track that refers to Domino Records’ shady handling of the sole album by Smith and Mouse on Mars collaborative project Von Südenfed, Smith reads from a dismissive email from Domino’s then general manager Jonny Bradshaw. Smith can’t be escaped. From beyond the grave, he materialises as the hobgoblin to further admonish, embarrass, and expose his enemies. At the end of the track, Smith says, “I think that’s the lot Jan thanks.” As the music lingers on, it’s easy to envision Smith walking away, slowly fading from reality as he blurs back into the otherworldly dimension that his spirit has claimed as his home in his peculiar afterlife.