There’s an extra frisson to seeing Rubika Shah’s debut feature in Berlin, a city, like so many across Europe presently, wrestling with the public re-emergence of far-right groups, mindsets and activity. The atmosphere during the Berlinale screening of White Riot, site of the film’s international premiere following its Grierson award-winning world premiere at the 2019 London Film Festival, is electric. There’s a palpable excitement tinged with the nervous hope that it contains a handy guide of how to fight fascism in the current moment, such that the introduction of the film elicits rapturous applause.

The applause at the end of the film is louder and sustained through the credits, and the film deserves it. It doesn’t present a how-to guide, doesn’t patronise its modern audience by pointing out the parallels it contains, and it doesn’t create white saviour figures of those responsible for the Rock Against Racism movement that emerged in late 1970s Britain, alongside punk, and a vicious and despicable cycle of hate crime and intimidation against people of non-white races and non-hetero sexualities. The grassroots growth and success of Rock Against Racism forms the basis for Shah’s documentary, which has evolved from her short film, White Riot: London, from a few years ago.

As a music documentary, formally speaking, the film is solid. It contains the increasingly conventional tropes of manipulated photo and video material, animated sequences, stylised interview settings and a strong blend of direct and contextual archive footage. It’s a commendable aesthetic entry into the genre, but it’s the stories at the film’s heart and their point of view where it really comes alive. There’s a refreshing directness and lack of sentimentality. The founders and key members of Rock Against Racism don’t see themselves as heroes, just people doing the right thing, and the film doesn’t paint them as martyrs either. Instead, the film offers a reminder of the role that white people can and have to play, through accessing their privilege, in civil rights activism.

White Riot also reminds audiences of the diversity of the punk community in late 70s Britain where race issues have been commonly reduced to a white (punk) and black (reggae) binary. The inclusion of the British Asian punk band Alienation, aligned with archive material depicting the difficulties faced by Bengali and other South Asian communities, is a powerful corrective. The tone of the film is direct and restrained, allowing audiences to grasp the modern parallels and see how nothing ideologically has changed. What has changed can be found elsewhere, including in the archive footage. Where once Nazis stalked British streets in large swathes, shouting their vitriol and intimidation, now much of this takes place online. English Defence League marches don’t contain the terrifying numbers that the National Front could muster but the racist mentality is still rife, targeted largely online, and in many ways activism has come to be seen as responding to Nazi trolls on twitter.

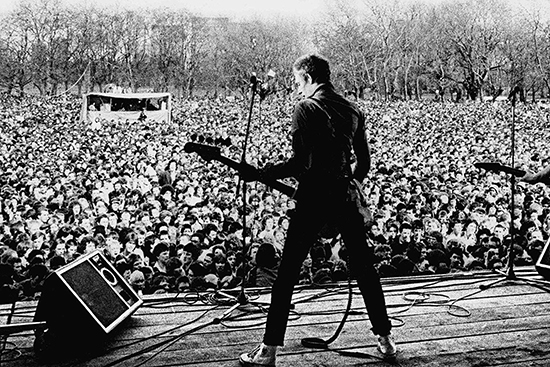

Shah’s film contains beautiful sequences of the people behind Rock Against Racism movingly reconnecting with the physical artefacts they created, most notably the anti-racist zine Temporary Hoarding. The messages of the zine were fierce and the issues themselves didn’t need to look as beautiful as they did, but as founder Saunders discusses in the film the movement grew out of a belief that art and culture could make a vital difference. The relationship between music and politics feels never closer aligned than when hearing Saunders talk over images of the hand-crafted issues that these people poured their heart and talent into and shared with the world. The labour of this, plus the writing of letters, the staging of gigs all over the UK, and the culminating famous Rock Against Racism gig at London’s Victoria Park – featuring X-Ray Spex, Steel Pulse, The Clash and the Tom Robinson Band – that the film is building towards, is a powerful take-away: action involves labour and labour can lead to momentum and impact.

The footage of the infamous gig, much of it taken from Rude Boy, the Clash film from the same period, is electric and serves as a release. It’s a vital release of anger, but also hope. The interviewees’ recollection of this brief but powerful resistance to rising national fascism, not just the Rock Against Racism gang but key musicians including Topper Headon, Tom Robinson and Steel Pulse’s David Hinds and Mykaell Riley, adds weight to the significance of this historical moment. Thanks to Shah’s concise and considered editing, it ensures the film builds to a euphoric close, sending audiences rushing to the streets looking for some fascists to take down.