Brad Bird’s feature debut The Iron Giant asks us to judge one another by our actions, and not by where we come from. In the DVD featurette ‘The Making of The Iron Giant,’ the director explains that the film really begins when Hogarth finds the Giant in pain. At that moment, he is no longer a machine; he is a being. Upon closer inspection, this friendly children’s animation presents a rich, layered story that explores what it means to be alive in a post-war world. 20 years later, it still rings true.

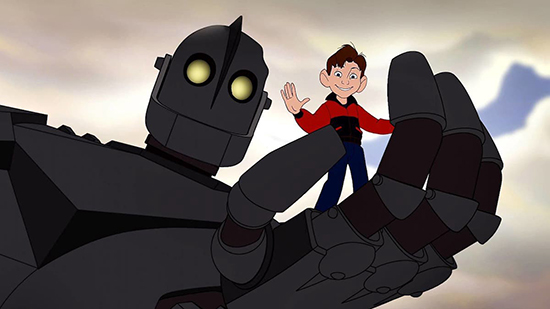

The year is 1957, and nine-year-old Hogarth Hughes is out playing in his hometown of Rockwell, Maine, when he stumbles upon a 50-foot tall, metal-eating robot. 3D-animated on beautifully hand-illustrated 2D backdrops, the Giant stands tall amongst the trees; a memorable picture for kids of the ’90s. The audience quickly learns that he is a specially designed weapon, when his automatic defense mechanisms are triggered upon seeing a ‘threat’ (Hogarth’s potato gun); though we never discover who designed him, or where he came from. But this doesn’t matter to the residents of Rockwell – especially in the context of post-World War Two paranoia. Bird explains that, at that time, “Everybody has been sort of conditioned to fear everything that’s not American”. It’s a climate that is emphasised when the seedy government official Kent Mansley says, “All I know is that we didn’t build it, and that’s reason enough to assume the worst and blow it to kingdom come.”

The story that follows is a gentle and compelling one, and telling it through Hogarth’s eyes ensures that the viewer shares an optimistic view of the Giant – we always believe he can defy his true nature. This is crucial, as Hogarth’s are the eyes the Giant himself learns to look through. If he didn’t view the world as Hogarth does, he would never make his ultimate sacrifice. It’s telling of humanity as a whole that the town’s officials wish to contain or destroy the Giant, whose views of the world best resemble those of a child, because he is different; not because of anything he has done or any demands he has made. It’s a startling look at xenophobia, an attitude that unfortunately has not disappeared in the 20 years since the film was released. In the context of 1957, people are fearful of another war. Revisiting it in 2019, it’s easy to now compare this to people’s fear of each other. Especially in North America, The Iron Giant feels as though it can be aligned with the rampant racism and xenophobia under Donald Trump’s administration – people fear that which is ‘unamerican.’ In Rockwell, that’s the Giant.

It’s always rewarding to look back at films that shook the status quo upon release, and to observe how that impact changes in a new context. Watching The Iron Giant as a child, it’s easy to get upset when no one gives the Giant a chance. When his hardwired defence activates, he struggles against it; he doesn’t want to be a destructive force, but it is all people see him to be. Looking back as an adult has given me a new understanding of the damaging nationalist attitudes of Kent Mansley and, if anything, makes it an even more heartbreaking watch. Mansley – confident, entitled, and the film’s true villain – lodges at Hogarth’s home to investigate sightings of the Giant, looking for any excuse to kill it, before it kills them. This inherent fear of what we don’t understand – especially if the ‘what’ in question can be weaponized – is not novel, but it is certainly unusual within an animated film, allegedly intended for children. It’s a parable buried deep within an enchanting tale, a story that becomes richer as you fondly look back.

A testament to the power of animated storytelling, The Iron Giant allowed the freedom of imagination for Brad Bird and his team. Where a live-action version could have sent costs through the roof, a hand-drawn story had no limits; meaning animators could send the 50-foot robot flying in the sky and easily secure the magic in stunning and skillful illustrations. Alongside its political mission, the film sees Bird do an expert job of exploring the identity crisis that arises when your role in the world is decided for you, as it is for the Giant. One particularly affecting moment showing this occurs when Hogarth excitedly shows off his comic book collection to his new friend. Flicking through the pages, the Giant sees an image that bears a striking resemblance to himself: Atomo, the ‘metal menace’. His expression is equal parts concerned and ashamed, as though wondering, “Does this mean I’m evil?”. Hogarth quickly shuts down this possibility, instead comparing him to Superman. Hogarth explains, “He’s just like you. He crash landed on Earth. But he uses his powers for good, not evil.”

The Giant looks to rebel against the very reason he was built, and reminds viewers that they can do the same – ignoring society’s expectations, choosing our own path. It’s a sentiment echoed in Hogarth’s desperate words, “You are not a gun. You are who you choose to be.” At the film’s heart-wrenching apex, a missile threatens Rockwell, brought on by Mansley’s reckless and fearmongering ambition. The Giant flies to meet it, whispering to himself, “…Superman.” This is a hero creating his own legacy. In doing so, he saves the town, and his best friend.

When I first watched the film, I was probably around seven years old. I didn’t know what it truly meant back then, but I wanted to be just like Hogarth. I dreamed of something crash landing on earth, like in The Iron Giant, E.T. or Lilo & Stitch. A ‘something’ that was destined to be my friend. For a kid who felt alone for a long time, the Giant filled that void and left his mark. He made me feel brave, and the effect he had on Hogarth he also had on countless children behind the screen, watching in awe. Now, at 21, I realise not only that the Giant is a friend, but also a representation of that precious flicker of selfless, courageous empathy that we all have. In the face of fear and prejudice, The Iron Giant asks us to find it again and to remember, “We are who we choose to be.”