Blade Runner may be best known as a film directed by Ridley Scott and loosely based on the Philip K. Dick novel Do Androids Dream Of Electric Sheep? Less known perhaps, is why the original title of Dick’s book was not used for the movie, and how that came from a sci-fi novella published in 1979 by William S. Burroughs. What even is a ”blade runner”?

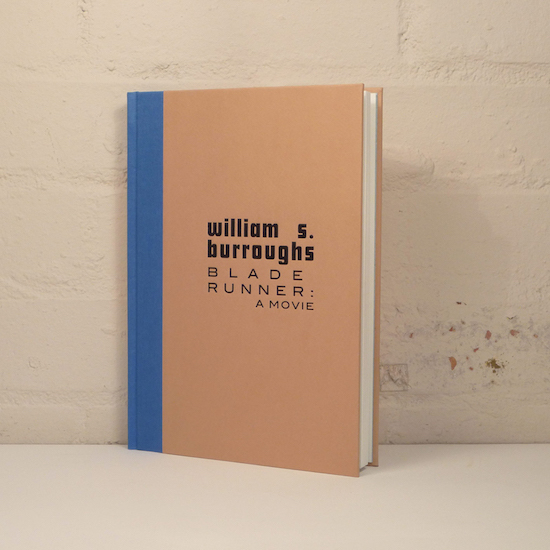

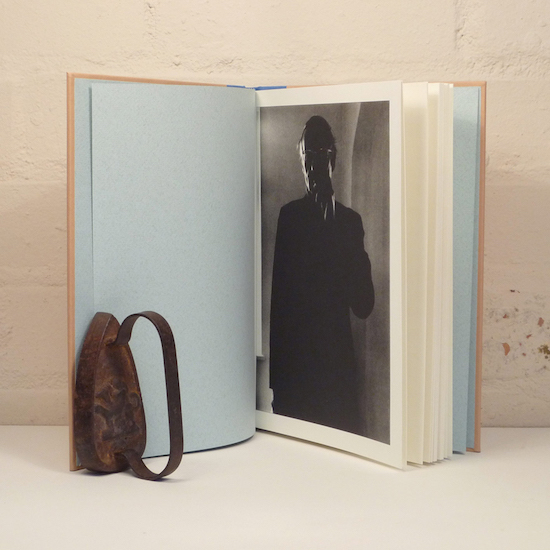

With a new edition of Blade Runner: A Movie recently published by Tangerine Press, we take a closer look to unravel the story behind the work by Burroughs and how it was inspired by Alan E. Nourse’s The Bladerunner, a pulp sci-fi novel from 1974.

Talking to The Quietus for this feature, Keele University Professor Oliver Harris, who wrote the introduction to the latest publication of Blade Runner: A Movie, said: “Like many people who have read Nourse’s 1970s novel, The Bladerunner, I only knew of it in the first place because of the Burroughs book which took its title. While most people who have heard of Burroughs’ Blade Runner only know of it because of Ridley Scott’s film that took his version of Nourse’s title. It is not just an odd chain of associations, but a weird backstory that tells us something about how the Burroughs virus spreads around.”

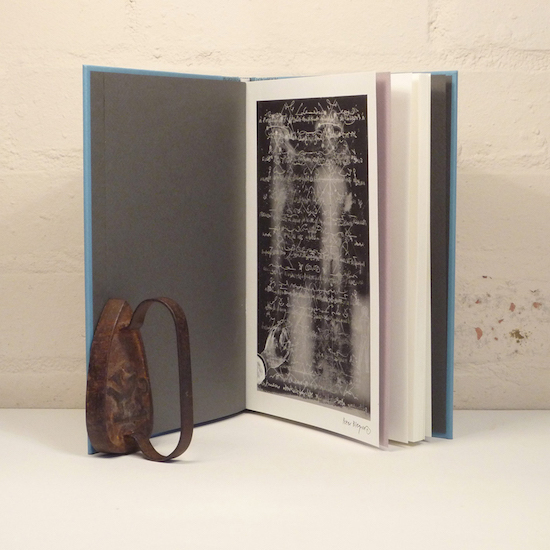

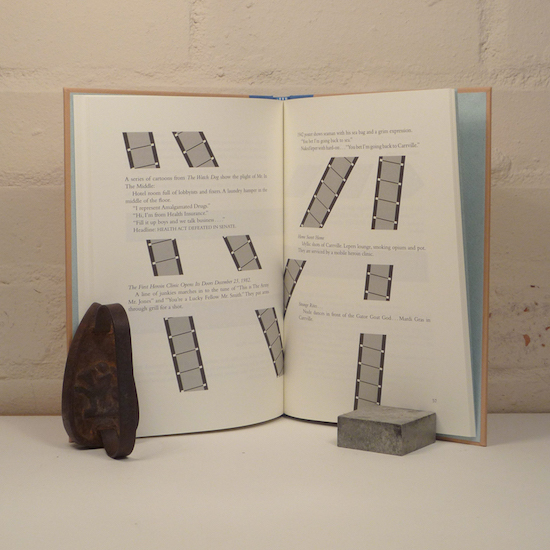

The origins of Burroughs’ interest in working on a film treatment for Nourse’s book date back to December 1976. Burroughs’ assistant James Grauerholz contacted his literary agent Peter Matson to give him a heads-up on a work taking in elements of Nourse’s original text that would draw on Burroughs’ interest in screenwriting. In print form, Burroughs’ book is broken up with images of cut-up film reel. As the subtitle suggests, Burroughs’ Blade Runner: A Movie is written not so much as a screenplay, but presented rather as a textual representation of a movie.

Harris said: “Reading one text against the other is fascinating, if at first quite baffling. What on earth did Burroughs see in this journeyman piece of genre fiction at the lower end of the airport or drugstore market? With no pretensions to be literary and lacking the garish imagination of the sci-fi pulps, Nourse writes pedestrian, realist prose with two-dimensional characters who all talk in the same colourless style. Clunky exposition and wooden dialogue has the effect of making the scenario of a medical apocalypse set in a decaying New York City drearily credible and oddly uninteresting. So, aesthetically, Nourse’s dull, laboured realism and tin ear for speech is the very antithesis of Burroughs’ writing, with its extraordinary economy, mastery of idiom, and wildly unbound imagination.

“As for what Burroughs took from Nourse: a few precise and not terribly significant borrowings and the general scenario, but far less than you might expect from a text published under almost the same title. But then, that is the point: the appeal of the title itself – evocative but elusive: what is a blade runner?

“It is therefore fitting that the title would achieve fame thanks not to Nourse’s novel or Burroughs’ use of it, but to the film by Ridley Scott based very loosely on the Philip K. Dick novel, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? The paradoxical, mysterious chain that connects Nourse, Burroughs and Scott seems itself to be a product of the enigmatic title that Scott chanced upon when reading Hampton Fancher’s 1980 screenplay for a film provisionally titled Dangerous Days.”

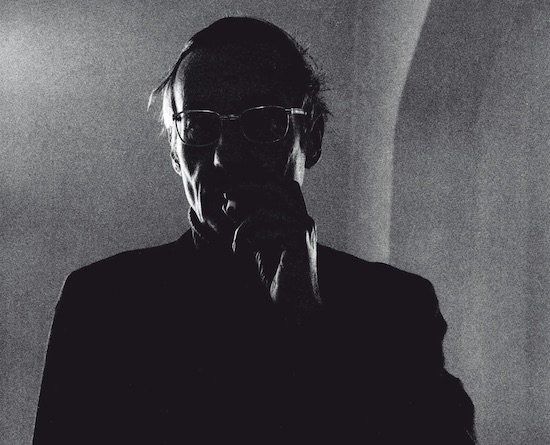

Living in an apartment known as The Bunker on New York’s Bowery after twenty-five years outside the US between Tangier, Paris and London; at the time of writing the book, Burroughs had been lecturing on cinema at City College. His interest in writing for film could be seen as a natural progression from his experimental cut-up film collaborations with Anthony Balch in the 1960s.

Harris: “After a quarter of a century as a writer in exile, the New York Burroughs arrived in seemed to be living out Nourse’s vision: the Wonder City of the future in a critical condition, on the brink of collapse and some kind of catastrophic mutation. Burroughs had had such visions as far back as his first novel, Junky, written in 1950: ‘I closed my eyes and saw New York in ruins,’ says the narrator during the depression of withdrawal; ‘Huge centipedes and scorpions crawled in and out of empty bars and cafeterias and drugstores…’

“As for why he wanted to turn Nourse’s novel into a film treatment, well, of course Burroughs had form in the use of screenplay format and movie terminology. Naked Lunch, in particular, is saturated with film dialogue and parodies of blue movies and TV commercials. And then throughout the 1960s, Burroughs collaborated with Antony Balch in producing and starring in short films like Towers Open Fire, that extended the reach of his cut-up project from page to screen. So there had long been a parallel trajectory of a cinematic aesthetic in his writing alongside the ambition to make actual films. This continued into the 1970s with texts like The Last Words of Dutch Schultz: A Fiction in the Form of a Film Script and plans for filming Naked Lunch and Junky.

“So there’s nothing unusual about Burroughs’ planned film treatment of Nourse’s novel. The book he published, however, is not a treatment or a screenplay but a typically hybrid text. Because it flashes back and forward in short scenes, you could call it ‘cinematic’. But you could just as well say that it defines itself against the plodding realist narrative of Nourse, cutting it up and throwing most of it away. It is not just an antithesis but a kind of aesthetic antidote.

“Burroughs may have felt at home inside Nourse’s scenario in other ways too. What is fascinating is to spot the points of intersection, the little hooks of coincidence that would have pulled Burroughs in from page one. Like the title of the opening section, ‘Billy’s Story’, or the description of his room with the ‘bare light bulb hanging from its yard-long cord’ that echoes the naked lightbulb that was the standout feature of Burroughs’ room at the Beat Hotel in Paris in LIFE magazine’s infamous hatchet job from 1959.

“You can imagine the little frisson of déjà-vu, the nod of his head. The signs were right.”

Reading Blade Runner: A Movie four decades on from its original 1979 publication, certain themes from Burroughs’ vision (via Nourse) appear to be eerily prescient, with a government concerned about overpopulation and gaining control over the private citizen. This is achieved through the ability to withhold essential services including work, credit, housing, retirement benefits and medical care through computerisation.

Nourse, who was also a trained doctor, set his novel in a dystopian US, where free healthcare is provided for all, as long as they undergo sterilisation and give up other freedoms.

Therefore, the ‘numberless’ population who do not submit are forced underground in opposition to what Burroughs describes as “brainwashed standardised human units postulated by such linear prophets as George Orwell.”

Harris said: “You can see the attraction in Nourse of certain ideas for Burroughs – medical pandemics appealed to his vision of a species in peril, a planet heading for terminal disaster – and in a parallel universe he might have done what Nourse did, combining a career as an MD with writing science fiction.

“We probably have the Nazi Anschluss of Austria to thank for cutting short Burroughs’ medical studies at the University of Vienna in the mid-1930s, and so indirectly giving rise to Dr Benway, rather than Dr Burroughs. Maybe that’s one reason Burroughs always took an outsider’s sceptical view of medical practice that drew him to the orgone accumulators of Wilhelm Reich and the apomorphine treatment of Dr John Yerbury Dent, unorthodox and experimental methods for succeeding where conventional treatments were failing – in Burroughs’ own case, of course, for drug addiction.”

In the book, blade runners are employed to run backstreets and alleyways to supply illegal medics with scalpels, drugs and supplies, operating outside of the law to treat the public as drug runners and informants when there is a deadly outbreak of illness. In Nourse’s book this is meningitis, and in Burroughs’ work, accelerated cancer.

Burroughs biographer Barry Miles compared the use of the term blade runner in relation to the ‘Roller Skate Boys’ featured in Burroughs’ The Wild Boys from 1971 and hailed Blade Runner: A Movie as “one very successful example” of Burroughs’ recurring “Wild Boys theme”.

In his movie, Scott used the term to refer to bounty hunters hired to ‘retire’ replicants.

You have to look both directions at once when assessing Blade Runner: A Movie, not just in looking back to it being inspired by Nourse’s book and in turn looking forward to the book’s influence on the film by Scott.

This philosophy of chronological disorder also runs throughout Burroughs’ text. Set in “a city we all know and love,” New York, in 2014, has become the “world center for underground medicine” and is the “most glamorous, the most dangerous, the most exotic, vital, far-out city the world has ever seen”. The Food and Drug Administration, American Medical Association and big drug companies operate “like an octopus on the citizen,” with service bureaucracies set up to deal with the problem of overpopulation.

Burroughs’ book itself acknowledges the dilemma of setting the scene in the lower Manhattan of 2014, saying this “poses a problem as to how background material is to be presented on screen. Postulate a story by an omniscient writer in the 1930s. Writer knows about World War II, the atom bomb, Vietnam, the drug problem, inflation, rock stars, gay lib, women’s lib, the Black Panthers. How, in terms of what is actually presented on screen, can we acquaint those living in the 1930s with a 1960 background, with what is common knowledge to anyone living in the 1960s?”

Burroughs’ takes the reader back in time to highlight significant events that shaped the environment he is describing. These include the Health Act Riots in 1984, following the launch of the first heroin clinics for addicts on Christmas Day 1983, when “some jokers dumped all the fish from aquariums, all the reptiles and amphibians, into the waterways of New York – and now freshwater sharks cruise the Hudson”. And back 23,000 years to the origins of the hitherto dormant Virus B-23.

Harris said: “The scenario about Virus B-23, the virus of biologic mutation that combats a cancerous pandemic threatening the human race, anticipates Burroughs’ much more substantial and successful novel Cities of the Red Night. But the significance of his Blade Runner can’t be grasped in terms of linear history. For the whole point of the text is to disrupt chronology – to fragment the kind of realist plotting that makes Nourse’s prophetic novel so tedious – and what goes for its own narrative goes equally for its place in the narrative of Burroughs’ oeuvre. As much as it flashes forward to Cities of the Red Night, it flashes back to bits and pieces from Naked Lunch, Nova Express and The Last Words of Dutch Schultz, creating a cross-cutting flicker effect that may be cinematic but is certainly disorientating.

“Indeed, on a first reading, it seems the text is all over the place – a chaotic mix of medical gags, provocative satire, repeating narrative episodes that jump back and forth but don’t ever add up. The archival history of the text (preserved at Florida State University) reveals that at least some of the confusions were accidental, but sloppiness takes on meaning in a cut-up context and, like a successful experimenter in any field, Burroughs had a genius for making good mistakes. So, re-read the text and the penny drops: causal linear logic is a one-way ticket, whereas hope resides in a different throw of the dice. Cut it up and who knows what might happen?”

Even though motion picture rights had been secured from Nourse’s agent, by the time the book was published Burroughs had given up on the idea of filming the story.

A screenwriter friend of Burroughs warned, “You’ll have to tear down New York for this film,” while Burroughs estimated that filming the riot scene from the prologue would cost five million dollars. So the book was published as an imagined movie rather than a real one.

Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner was not the first film to take influence from Burroughs’ novella. In 1983, Taking Tiger Mountain directed by Tom Huckabee and Kent Smith, included some of his ideas from the book, with Burroughs credited as a co-writer. The avant-garde film features a young Bill Paxton in his first movie role. He plays a researcher who is being brainwashed by a group of militant feminist scientists in a plot to assassinate the Welsh Minister of Prostitution. An early version of the film dated back to 1974 and filmed in South Wales and Morocco. However, when Huckabee purchased the rights to Burroughs’ Blade Runner: A Movie, additional footage was shot to include some of his ideas.

Reports in the film of a scarlet fever outbreak in the US, along with garbage and sanitation strikes, food rioting and sub-standard food sources were all central themes of Burroughs’ story. A news report bulletin, featuring Burroughs’ voiceover, documents a 1987 National Healthcare Package where “Massive immunisation has caused the collapse of natural immune systems which has, in turn, irrevocably soiled the gene pool.”

The 40th anniversary publication of Burroughs’ book also coincides with the setting of Scott’s 1982 Blade Runner movie in the present day, as the introduction credits note, “Los Angeles November, 2019”.

The origins of the film date back to 1980, when screenwriter Hampton Fancher was working on a draft of Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? by Philip K. Dick, provisionally titled Android or Dangerous Days. But originally, an early draft of the film was to be based on Burroughs’ novella.

George Mattingly, of Burroughs’ original publishers Blue Wind Press, said: “Filming of a screenplay lifted almost word-for-word from Burroughs’ Blade Runner was fairly far along when the production company was tipped off that the ‘screenwriter’ had actually taken our book nearly verbatim. They contacted us for permission but then decided they didn’t want to pay. The film then went through several ad hoc scripts before Ridley Scott took over the project and decided to base it on Phil Dick’s Do Androids Dream Of Electric Sheep? Burroughs’ influence on the Ridley Scott film remains in the look and feel of the degraded dystopian city of the future and in the attitude of its characters.”

The idea to replace Dick’s title with Burroughs’ work was made by director Ridley Scott, who noticed the term in an early draft of the screenplay: “The phrase ‘blade runner’ popped up… I thought, Christ, that’s terrific. Well, the writer looked guilty and said: ‘As a matter of fact, it’s not my phrase, I took it from a William Burroughs book.’ And the book, oddly enough, is called Blade Runner: The Film.” However, in what Harris describes as a typically “Burroughsian coincidence”, Burroughs had taken it from Nourse – so the phrase originated with neither he nor Fancher.

For Scott, the subtitle of Burroughs’ book, A Movie, was prophetic as it already anticipated its status as a film, albeit having been written as A Movie rather than a screenplay as he already envisaged that no film could be made from it.

Choosing to use the Burroughs’ version of the title follows Burroughs’ own philosophy about use of the word ‘the’. As he wrote in The Job: “The definite article THE will be deleted and the indefinite article A will take its place.”

As discussed by Genesis P-Orridge in a recent interview with ARTnews: “William Burroughs used to say, ‘Don’t use the word the.’ There isn’t the future – there’s a future, and for every single person that future is different.”

Harris said: “In short: there is something quintessentially Burroughsian about the process of adaptation, which is neither causal nor coincidental, but contingent in a way that worked out for everybody. Nourse’s potboiler retrospectively got a far larger and more literate audience; Burroughs’ otherwise minor text infiltrated the backstory of one of film history’s iconic works; while Ridley Scott – who probably knew even less about Burroughs than he did about Dick – acquired an avant-garde cachet that underwrote his cinematic vision of what would soon be called cyberpunk.

“Quantity and intention is therefore much less relevant than quality and affect when it comes to borrowing and adaptation, and in this sense the whole backstory has the logic of a cut-up operation. Scott took even less from Burroughs than Burroughs took from Nourse – just two words, ‘Blade’ and ‘Runner’, which came from Burroughs’ cut-up of Nourse’s original title, The Bladerunner. The differences are the smallest possible, but this is the molecular level at which Burroughs always worked with his scissors. So that the history of the title that went viral as it passed from Nourse to Burroughs to Scott, acts out the central subject of Burroughs’ plot: the possibility of favourable genetic mutations.”

While ‘blade runners’ as such do not appear in Dick’s novel, they are employed in Scott’s film to describe the agents hired by police to ‘retire’ – in other words execute – replicants. In the opening scene of the film, set at a Japanese street food bar, Deckard (played by Harrison Ford) is apprehended as a ‘blade runner’ by police as a ruse to summon him to the police station for a job hunting six replicants. Although he protests, “I don’t work here anymore,” police chief Bryant, who wants to enlist his services, insists, “I need the old Blade Runner. I need your magic.”

And just as that film went on to form a multiverse of differently titled versions, from The Director’s Cut in 1992 and The Final Cut in 2007, to 2017 sequel Blade Runner 2049, so too does the story of where the movie took its name.

Harris concludes: “Is it, therefore, just a meaningless coincidence that this new edition of Burroughs’ Blade Runner comes out in November 2019, the very date in which Scott’s film was set? Common sense says: What else could it be! But it is the hand of chance that created the beguiling connection in the first place. The function of prophecy in Burroughs is not to predict the future but to find meaning and maybe hope in the present moment, in our point of intersection with the apocalyptic fiction that we’re living out, right here, right now.”

Blade Runner: A Movie by William S. Burroughs is published by Tangerine Press. Oliver Harris is co-organising a series of William S. Burroughs related events by the European Beat Studies Network in London and Paris next year to mark 60 years of the Cut-Ups.