Even within the wave of German groups of the late 1960s and early 70s that came to be labelled krautrock, Can, the band that Irmin Schmidt founded in Cologne with Holger Czukay, Michael Karoli and Jaki Liebezeit, stood out for their fierce commitment to experimentation that went way beyond space-age effects and a motorik beat.

His 100 or so soundtracks for film and television include a string of collaborations with Wim Wenders; he has conducted symphony orchestras and composed an opera, Gormenghast, based on the gothic fantasy novels of Mervyn Peake; he has also been a student of Karlheinz Stockhausen and Gyorgy Ligeti. His contribution to music has been recognised in France, where he now lives, with the Ordre des Artes et des Lettres.

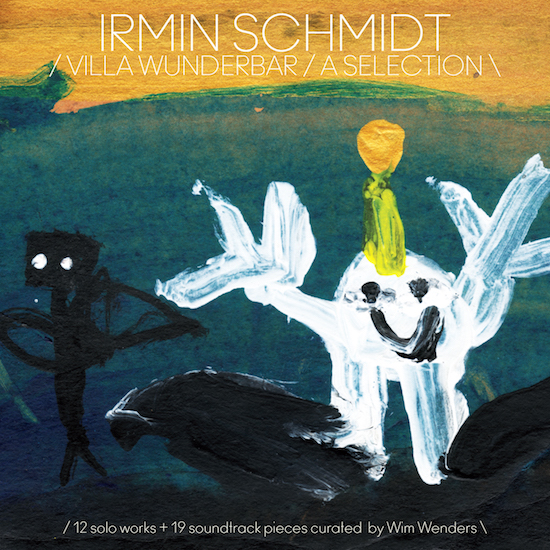

It is far more than can be squeezed into a four-album box set, but the new vinyl pressing of Villa Wunderbar has a decent try. “I’m interested, I want to make people interested,” the 82-year-old says of the set, initially released on CD in 2013. Its musical scope suggests a restless and inquisitive mind. “I wouldn’t call it restless because I’m pretty relaxed about it,” he says, “but I’m always interested to do something new and I want to be surprised, even by my own stuff, so I always change direction.

“Actually it looks and it sounds surprisingly different than what I did before, that was the same with Can, but it’s always around the same compositional problem. I want to bring together all these new musics which appeared in the 20th century in Western culture, so that means there was our classical music which developed into contemporary music like Stockhausen and Poulenc – I studied with them so I’m very at home there. I conducted classical music and played it on piano, so I’m very at home there.

“But then I listened to a lot of jazz and I thought jazz is another new music, totally new in our culture, and then rock appeared. It’s another version, it’s something developed out from folk and jazz and blues, and all this is new. And I wanted in always a new kind of way, to find ways to bring it together, to make music which contains all these new [forms] and not to overuse one aspect doing serial atonal new contemporary or electronic or only blues or only jazz in classical way.

“I wanted to bring it all together and every composition I do I sort of combine all these influences in a different way. Since this history of music in Europe and America in the last 100 years is so incredibly rich, because it has so many different influences from all over the world – we got influenced by jazz and blues and all that, which has African sources, and I studied also Japanese Middle Age music – I suck it all into me and very time something comes out it contains all that, but every time in a different variation.”

The film music on the box set was selected by Wim Wenders, with whom Schmidt – and Can – first worked in 1973, on the film Alice In The Cities. “It’s very easy to work with him,” Schmidt says. “The last thing I did with him was the film Palermo Shooting. I saw the film together with him and during looking at it I all of a sudden had the idea what about using this Bach theme from Matthäus Passion but let it play on a Neapolitan accordion and so give this beautiful melody a totally different atmosphere and in context with the film again it will change. So I told him, ‘What do you think?’ and he said, ‘A very surprising idea, but do it’.”

Schmidt’s approach to composing for film varies according to each director’s vision. “Film is team-work, so you listen to what the director, or sometimes the producer too, has to tell you, how they see the film, what they want to tell. You don’t want to mess it up so of course you discuss it. Before I am discussing it with them, I look at it alone, I have my own opinion, so with my opinion and my ideas we discuss it very carefully and come to a solution. After I have finished composing and putting it on the computer then he comes and proposes what he would like to change, we discuss my work again and makes nearly always little changes because of a sudden he likes some kind of melody ands says, ‘Why don’t you bring it a little more often, for instance here or there’, or the opposite, saying, ‘I think there should be no music’. That’s normal, then we work two, three or four days together, sometimes only one, just depending, and then it’s done.”

Reflecting on his days in the classical world, Schmidt once said having had total control while he was conducting an orchestra, he founded Can for the opposite reason. The avant garde band, who formed in Cologne in 1968, he says, a democracy. “No hierarchy, not at all, difficult sometimes,” he says. “That was the idea and it worked at least for ten years, and after those ten years on a lot of my solo work and a lot of my film music Jaki and Michael played, so until they died we were very close and worked together from time to time.”

The band went through various line-up changes before splitting up in 1979; later reunions were short-lived. Karoli died in 2001; the deaths of Liebeziet and Czukay in 2017 left Schmidt as sole survivor of the core line-up. He says he sees it “less as a duty” to preserve Can’s legacy “as it’s in me, it’s in my body”.

“Pure business-wise, preserving it, that is more Hildegard [Schmidt’s wife] and Spoon Records, and I help her with that. Next year we will release a series of live recordings because there is this guy who was collecting that all over the place during Can’s time. He has been writing to people to give him a copy of what they cut and all these live recordings of course are very amateur, sometimes very bad quality, so we didn’t think about getting them published or on a record, but now through the autumn with our sound engineer I listened to hours and hours of concerts and I found some which are brilliant and the quality with modern technology can be improved, so we will release a series of live concerts next year.”

Schmidt’s life before Can was extraordinary. Born in Berlin in 1937, he evacuated to Austria with his family in the Second World War. They returned to Germany “in total ruins” in 1946 and through his adolescence Schmidt found himself deeply at odds with his Nazi-supporting father. “Of course I couldn’t relate to the fact of coming back to Germany, because we spent the last years of the war in Austria, in the Alps, where it was very idyllic and you didn’t feel the war,” he says. “Then coming back first to Nuremberg and then to Dortmund, which had been the most important area for mining and the steel industry, it was totally flattened, and that for a young boy of eight or nine years old is something traumatising, of course. You don’t really understand the world. So that is a part of my experience which I deal with all my life.

“It was not only the material destruction, it was mental destruction, the destruction of these thousand years of our culture. When you are young it’s no so easy to deal with that. Of course there is something resting in me about that, a kind of mourning.”

Schmidt devoted himself to classical piano, studying in Dortmund, Essen and Salzburg before a spell at the Rheinische Musikschule in Cologne, where he met Czukay and was taught by Stockhausen. He says the one of the visionaries of 20th century electronic music was a “very severe” teacher. “But then he could be very relaxed and very funny, full of humour. He invited his students, we had wonderful parties all night long at his house, but when it came to work, he was very strict. In the beginning of the Sixties he was very dogmatic, later he got more relaxed about it, he accepted other things which before he didn’t. The older he got the less he was dogmatic, but in the beginning in 63 when I was in the Arnstadt at his courses, there he was very, very dogmatic.”

A visit to New York in 1966 has often been cited as the point at which Schmidt began to turn away from classical music. But he says even before then he was listening to jazz and rock. “Even during my very intense third year studies with Stockhausen and Ligeti, I was conducting and performing on the piano a lot of contemporary music like Messiaen and Webern and Stockhausen too, but at the same time I was a young man, I was going to parties, I listened to pop and rock music. I listened from my 15th year on with growing fascination to jazz. I had quite a lot of jazz records, even while I was studying and practising classical music I listened to them quite a lot, so it came very naturally, and then something that was like a revelation: I heard Jimi Hendrix playing and I realised this can really be art.

“What he did in Woodstock with the American hymn [‘Star Spangled Banner’], the improvisation he did there on the guitar meant to me there is somebody who creates a new instrument. He was recreating as a new instrument the guitar. It’s one thing in rock as well, in every music, great musicians when they play very often they turn it into a new instrument, like Coltrane or Charlie Parker made it with the saxophone, and Miles Davis with the trumpet, but Beethoven already made it with the piano, because when he played piano it became a new instrument. Ands again, in the end of the 19th century, Liszt, for instance, turned the instrument into something new, no one ever played like this. The builders of piano had to changer the instrument to get what these musicians wanted from it. Beethoven played so fiercely and destroyed so many pianos that they had to make it stronger and bigger and the sound bigger, and that’s what Jimi Hendrix did, he created a new instrument. I was so fascinated by him, that was one of the key events.

“But in the beginning I didn’t want to sound like a rock group, I wanted to find a groove which contained rock and jazz, contemporary new music and electronic, and combined it, not just by saying I’ll make some weird modern harmonies and some weird asymmetric rhythm to it and maybe some electronics on it. I wanted the musicians I put together to represent a kind of history, like Jaki, he had a long history of jazz playing, Holger and I had a long history of playing contemporary classical music. Of course we weren’t just teenagers, we were already 30. Michael was ten years younger but he had experience in what they called at the time a beat guitarist, a rock guitarist, so I brought together these styles as persons, not as a composer who puts ideas together, and that made it an exciting and difficult adventure and finally successful.”

Schmidt sees his entire career as an extension of those principles from the 1960s. “I’m continuing putting them always in a new context,” he says. “The music comes out of this special body, this special brain, these hands and this belly.”

‘Klavierstucke’, which he will perform at Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival in November, was first improvised on two pianos – one prepared, the other as normal. “That was played on the spot, no correction, nothing which was on the CD, so I wouldn’t play the same pieces the same way,” he says. “I can’t repeat that, and I would not at all start learning them to play to repeat them, I will do something else. I will play something which is near to ‘Klavierstuck II’, it will have a kind of similarity as it uses the same mental sound but then I will do some new pieces, again totally different.”

For Schmidt, the Klavierstucke album he released last year represents “more than 40 years work”. He sees parts of all the things he has written in there. “They are in me and of course they are in the music, because all my experience, that’s how life is,” he says. “You don’t start life every day from scratch, it’s all in you. I find in the course of the years it changes; as I said, I want to turn this basic idea to use all this rich material of music. You know there has never been in our history a moment where we had such a mass of history present around us, like a big room, a big space, and there are 600 or 700 years of European classical music behind us, but it’s all there because you can go in a record shop or you take it from the web and you can listen to it, it’s present.

“Before it was history, now it is something which is absolutely present. You can listen to any kind of music of the last 600 years, you can put a record on and listen to it and also you can listen to jazz, but not only jazz which somebody makes in the present, you can listen to Big Bill Broonzy and Bessie Smith or to Charlie Parker and to the whole history of it, and to the whole history of rock, you can listen to Asian music, to music from Bali which they made 200 years ago in the tradition, you can listen to African music. You can even travel easily in these times – I went to Senegal and listened to musicians, and fantastic music from Mali, I realised some of the music they play is pure blues. So all this rich music and history and narration is around us now. We live in a space where you just go three steps and you have history, you go in the next direction and you have another history. All this presence of history, this mass, some people find is too much, but I find it wonderful and I use it.”

He still makes time to play the piano every day and says there will always be part of him asking musical questions. “Yes,” he smiles softy, “and it still keeps the unanswered question.”

Villa Wunderbar is released via Mute on 22 November. Irmin Schmidt plays at Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival on Thursday 21 November