In the recent film, Leaving Neverland, one of the men who alleges he was sexually abused by Michael Jackson as a child, makes the astute point that it’s difficult to remember just how famous Jackson was during the 1980s. And it’s true, he was a rock star nonpareil, flashing a single white spandex glove festooned in Swarovski crystals, hiding his face in a surgical mask, perhaps to conceal the scars and the damage from further rounds of plastic surgery. He was arguably the most famous man in the world, as ubiquitous as Coke – although he was an ambassador for Pepsi, the darling of the then inescapable MTV and no.1 target of the red tops. Were he alive and active now with the same levels of interest then even the parody Twitter account for his pet chimp would have millions more followers than you. Jackson’s enigma fuelled a peculiar exoticism and, as is often the case, also led to lazy assumptions about idiosyncratic behaviour equating to genius. As he said himself in the Thriller video: “I’m not like other guys”, but interest in ‘Wacko Jacko’ was rarely of a prurient nature (in the same way as it wasn’t with Jimmy Savile); the wackiness somehow concealed darker secrets.

Jackson sold as many records as the Rolling Stones and Abba put together, and his sixth studio LP, Thriller, is the best selling album of all time, going platinum 29 times and shifting an estimated 66 million copies when last verified by the Guinness Book Of Records in 2017. Only The Beatles and Elvis Presley have sold more. And yet the fairy tale would turn sour when his interest in children came under scrutiny. Michael, it was always Michael, liked to promote the idea that he was childlike himself – an innocent, too pure for this world. But the scales began to fall from people’s eyes in 1993 when the first child molestation allegations were made against him, and then swept away with a cheque reportedly to the tune of $23 million. More allegations would follow.

What damage these latest testimonies will do in the long run remains to be seen. Many of his 2.2 million followers on Twitter choose to soldier on with vision-impairing blind spots, but will future generations forget the allegations so easily? Or millennials for that matter. “I have never really associated Jackson with his music,” wrote music journalist Laura Snapes in a piece for the The Guardian published in March which asked, Can we still listen to Michael Jackson? “I was born in 1989, and grew up in a pop landscape where he was decreasingly visible. His songs remained totemic, but so much so that it rarely occurred to me that they had been made by humans, the same way that I never wondered who designed the McDonald’s logo, or what’s really in a can of Coke.” Snapes goes on to say that “Jackson’s greatest legacy is as an unparalleled example of how the entertainment industry prioritises profit over pain. It’s a cautionary tale against idol worship, and a reminder to question figures who willingly exploit that dynamic. This is the point where, for me, the man and the music become inextricable, and forever inadmissible.” In the same article, the American essayist Charles Klosterman, isn’t quite so sure: “What is specifically complicated about the Michael Jackson scenario is the sheer magnitude of his footprint. Even if every worldwide streaming service removed his songs and Apple Music terminated his catalogue, there are still at least 60m physical copies of Thriller scattered around the globe. He is too massive to cancel.” Klosterman, it should be noted, is 47, and would have been a teenager when Jackson was at the pinnacle of his powers.

When Jackson died in 2009, I remember observing a boy of seven or eight cycling along in Stoke Newington singing his heart out to the chorus of ‘Beat It’. It reminded me in that moment of the impact the death of John Lennon had on me at the same age. I’d never knowingly listened to the Beatles, but given the way my mum and Frank Bough were reacting to his sudden death, I became immediately enchanted once all the old albums got pulled out of the cupboard. This introduction to the Beatles led to a lifelong obsession with pop music. It warmed my heart to think that out of the tragedy of Jackson’s death, a whole new generation might discover his music, or music in general. As things stand, future generations may never get to know his music or, while they will be aware of it, there will be caveats attached. Richard Wagner still gets played, but never in Israel, and you don’t need to be in a room with Ken Livingstone for someone to mention Hitler as the familiar refrain from Ride Of The Valkyries rings out. Will people not yet born come to regard this 20th Century figure as a cautionary tale? Or worse still, will the cancel culture that permeates social media right now lead to his legacy being wiped from our memories?

Cancel culture, or call-out culture, is a recent phenomenon by which artists or public figures are immediately sent to a perpetual Coventry for actions or thoughts deemed inappropriate by the public, usually via social media, though not always. Kevin Spacey, Louis C.K., Rosanne Barr, Mel Gibson, Ryan Adams and Woody Allen are just some of the names who have fallen foul in recent years and had their work boycotted in this manner. Attempts to reanimate a career too soon or engage with one’s audience without expressing the right kind of contrition will only lead to mockery, and ultimately, failure. The word ‘cancel’ has a finality about it, so contrition is rarely enough to lift a star from their enforced purgatory. Sometimes only death will exonerate, like in the case of Jade Goody – perhaps one of the first to befall the wrath of call-out culture after making racist comments on Celebrity Big Brother 5 in 2007.

Contrition is obviously impossible from Michael Jackson on account of him no longer being with us, and any redemption looks unlikely. Cancelling an artist who has already sold £350 million albums and hasn’t drawn breath for ten years feels a bit like locking the stable door after the horse has bolted. Jackson is no longer subject to the capricious nature of attention economics and he’ll never need to apologise to anyone that he hurt, contritely or otherwise. Nor will John Wayne, who was “cancelled” in February for some horrendous views that resurfaced from a Playboy interview he gave in 1971, where he admitted he was a “white supremacist” in theory, called gay people “fags” and said they were “perverted” and suggested the indigenous peoples of the Americas were treated fairly by pilgrim settlers who stole their land, gave them smallpox and confined the survivors to reservations. These views come as little surprise to those old enough to remember Wayne when he was alive, but despite having been dead for 40 years, he was still pilloried and sent to the eternal naughty step by people who probably wouldn’t watch his films anyway.

The evolution of cancel culture has, for the most part, developed online, as we’ve offered more and more information about ourselves to the public domain. In 1997, the sociologist Thomas Mathiesen proposed the Synopticon, a kind of inverted 20th century version of Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon, where instead of a centralised figure surveilling the many, the many had begun to surveil the few. Television, radio, newspapers and mass media gave us a window into the lives of the rich and famous that most of them probably didn’t like. Social media has amplified that access, while old tweets don’t go away, meaning something expressed clumsily while drunk a decade ago can suddenly be dredged up from nowhere. Views that might have been frowned upon can, in the highly-charged world of cancel culture, suddenly look, at best, anachronistic and, at worst, a reason to jettison the author of the questionable or unpopular opinion into oblivion. What’s more, an entire generation has grown up excluding problematic people – racist aunts or attention seekers – by either hiding, muting or unfriending them on Facebook or Twitter; that this extends to celebrities or people who are being made an example of or long dead musicians with questionable sexual mores, looks like a logical, systematic progression.

This new dynamic can empower minority groups and shift the balance of power as well as topple once-untouchables who could previously damage those around them with impunity. It’s a welcome development, but there can be downsides. The pressure to agree with the punishment meted out can be intense, and sometimes those who attempt to empathise with, or come to the defence of, someone in the firing line can bring the backlash onto themselves. Also, is being on the side of righteousness justification enough to become a bully?

Jon Ronson first noticed the power of publicly shaming in 2009 when Jan Moir of the Daily Mail wrote a nasty column in response to the death of Boyzone singer Stephen Gately. Following a concerted campaign highlighting her bigotry, Marks & Spencer and Nestlé pulled their advertising from the paper. “These were great times. We hurt the Mail with a weapon they didn’t understand – a social media shaming. After that, when the powerful transgressed, we were there,” wrote Ronson in his 2015 book So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed. “And then one day it hit me. Something of real consequence was happening. We were at the start of a great renaissance of public shaming. After a lull of 180 years (public punishments were phased out in 1837 in the United Kingdom and 1839 in the United States) it was back in a big way. When we deployed shame, we were utilising an immensely powerful tool. It was coercive, borderless, and increasing in speed and influence.”

Shaming or cancelling doesn’t always work. A declaration on social media may only extend as far as the person saying it, but it can also escalate and the offending star or civilian or limited company become persona non grata with a terrifying swiftness. People have tried, and failed, to cancel President Trump, who weathers a litany of sexual impropriety charges by being repugnant and the most powerful man on earth. What applies to actors who cast themselves as sensitive, compassionate and progressive, doesn’t necessarily work with right wing demagogues.

Musicians arraigned with sexual impropriety might feel hard done by and point to the fact that the goalposts have moved, protesting that what was once part of their job description is now taboo – but it doesn’t matter in the reckoning. A plea of “they were different times” would never stand up in court where the King of Pop is concerned, but where does one draw the line? What happens to your records by great artists with shady reputations or skeletons in their closet: John Lennon, Jimmy Page, James Brown, David Bowie, Miles Davis, Iggy Pop, Lou Reed, Nina Simone, Elvis, Chuck Berry, Frank Sinatra, Leadbelly, Kanye West and so on and so on? Does Ian Curtis get chopped because he voted Tory, or Kate Bush because she once said Theresa May was “wonderful” (perhaps gauging the temperature in the room, Bush issued an uncustomary clarification)?

Then there’s Morrissey to consider, even if one would prefer not to. Some have chosen to bifurcate the work, discarding the Pope of Mope’s more problematic latter output while keeping hold of their beloved Smith records when he was assumed to be more liberal and egalitarian. But we can’t say that we weren’t warned. He told Melody Maker in 1986: “I don’t have very cast-iron opinions on black music other than black modern music which I detest. I detest Stevie Wonder. I think Diana Ross is awful. I hate all those records in the Top 40 – Janet Jackson, Whitney Houston. I think they’re vile in the extreme… Obviously to get on Top of the Pops these days, one has to be, by law, black.” Then there’s this passage from Johnny Logan’s Morrissey and Marr: The Severed Alliance published in 1992, which would have prompted Moz to reach for the wet plimsoll: “Even while denouncing racial prejudice in stirring fashion, he was wont to admit that he disliked Pakistanis. ‘I don’t hate Pakistanis, but I dislike them immensely,’ was his flippantly blunt adolescent observation… Years later, he revisited and, some would argue, reiterated those old prejudices in his controversial composition ‘Bengali In Platforms’”.

Hanging onto the Smiths whilst cancelling Morrissey is a facile gesture that smacks of sanctimony without sacrifice – like being vegetarian but still eating roast chicken on Sundays (which Morrissey certainly wouldn’t approve of). And it’s these inconsistencies and these hypocrisies that make cancelling very difficult to apply with any fairness or rationality. Perhaps forming a quiet, considered, personal preference and course of action without judging the motivations of others is the best way forward. Personally I can’t listen to Morrissey or the Smiths anymore. While I’m not ruling out reconciliation in the future, these records are probably best left where they belong with my memories of my teens and twenties.

As for Michael Jackson, could all this concern about his legacy be a red herring? While many have pondered the improbability of his music surviving such terrible allegations, I find it hard to believe that he’s endured for as long as he has given how patchy so much of his oeuvre is. Nobody can doubt his talent or his star quality, but perhaps his enormous contribution to pop is more a received wisdom than an inadmissible truth.

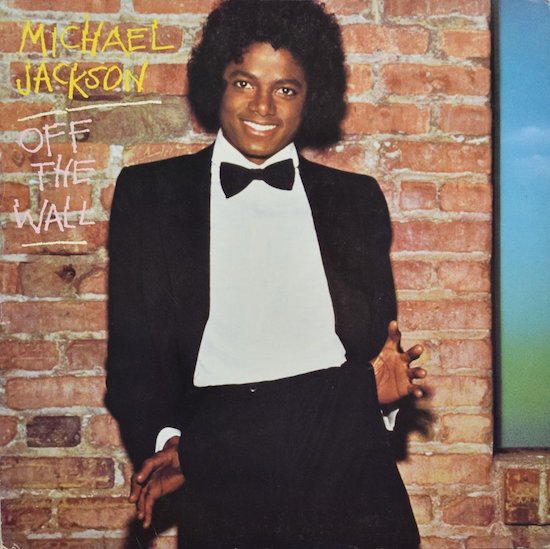

Let’s start with his best album, Off The Wall, which was released 40 years ago and still sounds as effervescent as the day it dropped. It may have been his fifth studio album under his own name but it’s the real starting point for Michael Jackson the solo artist. Hitherto, Jackson had been mentally and physically abused himself as a child by an overbearing father, and had his artistic freedom curtailed by the Motown hit machine. The big songs were sporadic, including a US Billboard No.1 about a rat. The four albums were no great shakes with an impossibly young star going through the motions, recording whatever he was instructed to sing.

When the Jackson 5 left Motown and became the Jacksons with CBS, his songwriting abilities slowly began to emerge. ‘Blues Away’, written solely by Jackson on the eponymous debut, showed promise; by 1980 he’d written ‘Can You Feel It?’, his first truly great song for the band with his brother Jackie, but by the time that was released as a single in 1981, the writing was already on the wall for the Jacksons given the phenomenal solo success he was having; success that would prove to be just a taster. For all the talk of the infamous Disco Demolition Night sounding the death knell for disco, it couldn’t lay a glove on Michael Jackson’s Off The Wall, released a month after Steve Dahl’s racist publicity stunt at Comiskey Park in Chicago. Off The Wall is mutant disco, a super virus that few immune systems can resist. Opener ‘Don’t Stop Til You Get Enough’ is an irrepressible, unbridled marker, enabled by Quincy Jones’ cowbell-driven funk and sliding, giddying strings. It’s a mission statement that alerts us that the shackles are off. Michael Jackson is finally free and he’s living in the moment.

The Rod Temperton-penned ‘Rock With You’ brings an added smooth, soulfulness that will be even more influential in the coming decade. The title track, also written by Temperton and cast in the mould of his previously-penned Heatwave classic ‘Boogie Nights’, proved there was plenty of life left in funk-disco, while Jackson’s own ‘Workin’ Day And Night’ appears to anticipate Italo house by a decade and is infused with a strong work ethic both musically and lyrically, the latter of which, with lines like "You say that workin’ is what a man’s supposed to do", has the air of blue collar fetishisation. It can’t be denied that Jackson was a worker bee, in the studio and on stage – much of what came after Off The Wall would suffer from him trying too hard. The smooth, swooping, sumptuousness of ‘Don’t Stop Til You Get Enough’ is a world away from the laughable, cartoonish ‘Bad’ or the constipated, frustrated, hateful ‘They Don’t Really Care About Us’ (originally featuring the anti-semitic lyric: "Jew me, sue me, everybody do me / Kick me, kike me, don’t you black or white me").

Off The Wall is a great, albeit uneven, long-player, with the first side reaching perfection, while the flipside is a little Stephen Sondheim-lite in places. ‘Girlfriend’ is a Paul McCartney song written when he was going through his marshmallowy, tossed-off, “this’ll have to do” period before he reawakened his artistic curiosity with McCartney II. ‘She’s Out of My Life’ features that slightly-sickening, winnowing piano that would become omnipresent on ostentatious Whitney Houston ballads-by-numbers throughout the 80s and 90s.

Up next was Thriller, the best selling album of all time, but certainly not the best. This was the first album I bought as a nine-year-old and, as my only long player for a few weeks at least, it spun many times on my hi-fi and created plenty of excitement for all the family. It’s odd to listen to it now after all this time because so many of the songs simply drift and fall away. The chorus of ‘PYT (Pretty Young Thing)’ is an enjoyable surprise 37 years on, but the rest of the song is lost to me, as is the whole of ‘Baby Be Mine’. ‘The Lady In My Life’ by the normally reliable Temperton should finish the album with a flourish but brings cruise ship blandness instead of a climax. ‘The Girl Is Mine’ is a hokey sitcom with Paul McCartney, who definitely got the better end of the deal (the reciprocal ‘Say Say Say’ appears on Pipes of Peace). And then ‘Human Nature’ was part-written by Steven Porcaro of Toto, but it’s no ‘Africa’. Jackson too was as far removed from humanity by the time Thriller surfaced in 1982 as most tin-pot African despots.

What’s truly surprising is that out of nine songs, a record seven made the Billboard top ten, an astonishing feat for a record with so many forgettable songs. There are moments that have left a lasting impression, of course: ‘Billie Jean’, with its aching, undulating bass groove and a truly mesmeric performance from Jackson, rightly deserves its esteemed position among the greatest pop songs ever made. The title track too, written by Temperton, has a Halloween-y, kitschy charm to it, but it’s Quincy Jones’ extended funk breaks strung together during the video that steal the show. Meanwhile the opening gongs on ‘Beat It’ are as indelibly stamped on my brain as the opening bars of Beethoven’s 5th and yet I can’t hear the ensuing drum machine without remembering ‘Weird Al’ Yankovic’s squeaky toy sounds on his pointless pastiche ‘Eat It’. ‘Beat It’ is also the first of a number of “rock” songs that Jackson simplistically makes about conflict. It’s as though he assumes that distorted guitars must spell trouble.

On 1987’s Bad – which sold 35 million albums and consolidated his place in the pantheon – he seems to have deluded himself that he’s a badass, heading for the border to evade capture on ‘Speed Demon’, dressed like a gangster in the video for ‘Smooth Criminal’ or in black S&M gear for the title track playing the intermediary between rival ruffians wielding flick knives. ‘Dirty Diana’ is misogynistic and weak; ‘Man In The Mirror’ is pure self-indulgence by a megastar with no self-awareness other than of his place in history. What’s more, the grunts and whoops that used to be a means of expression have become ticks, and Jackson, a Frankenstein’s monster of sad self-parody. He is incapable of changing – not really. His rock posturing never grabs the nettle. Truly great pop stars, the Bowies and Madonnas and the Princes, are able to reimagine themselves and assimilate to their musical surrounds, but it’s ever diminishing returns from Off The Wall forwards for Jackson, suffused more and more with the growling and howling of a once great pop star who has lost his handle on creativity.

More records were broken, but the artistry was shot: ‘Scream’ with Janet Jackson is apparently the most expensive video of all time but who can remember the tune? ‘Black And White’ was awkward at the time given the rumours of skin-bleaching, though it now looks as though Jackson suffered from vitiligo, a further blot of shame on the gutter press. The album was called Dangerous, which again looked try hard at the time and with hindsight could be regarded as the double bluff of a predator hiding in plain sight. HIStory tried to reclaim Jackson’s place at the top table after so much bad publicity but lacked the charm of past endeavours; Invincible in 2001 featured persecuted, passive aggressive songs like ‘Privacy’, with the highlight being a second-hand rap by the late Notorious B.I.G. lifted from an old track by Shaquille O’Neal. Farce seemed to follow Jackson wherever he went after the allegations, be it down the Thames as a 50ft statue, or a gaudy one outside Craven Cottage, or at the BRITS, where ‘Earth Song’ is best remembered starring Jarvis Cocker’s billowing buttocks. Then there was MJ’s final no.1, ‘You Are Not Alone’, written by that other Pied Piper of pop, R. Kelly.

Perhaps the biggest surprise of all isn’t that Jackson’s star has continued to burn bright, even after such damaging allegations, but that he’s maintained such a presence despite only releasing one truly great record. Michael’s reputation might be done for, but the devaluation of his stock may just be beginning. Cancel Michael Jackson for all I care, but I’ll be hanging onto my copy of Off The Wall and listening to it sporadically without a shred of remorse.