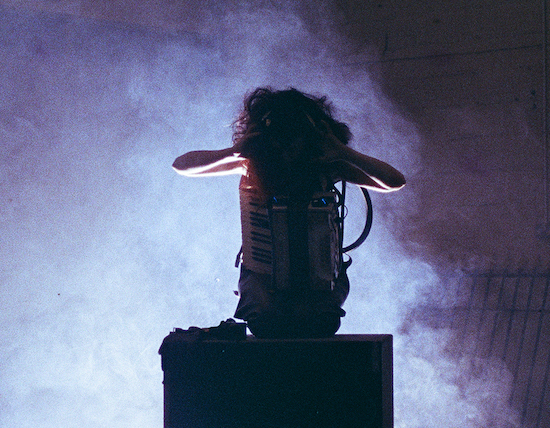

World Zero live photograph by George Lane

The Seer, IMPATV and UKAEA present World Zero at Supersonic Festival on Sunday 21 July

In Greek mythology, Cassandra was bestowed with the gift of prophecy by Apollo. But after rejecting his advances, Apollo retaliated by ensuring that no one would ever believe her. Cassandra thus became cursed to know the future without having the ability to influence it. This frustration, of being caught between knowledge and powerlessness, is perhaps why her character still resonates today. The continued popularity of the I Ching, the spike in interest around the Mayan calendar back in 2012, and the current millennial penchant for astrology all represent ways in which ancient traditions of divination can be resurrected to try and make sense of our increasingly unfathomable world.

Artist Conny Prantera has built a striking career out of channeling precisely these concerns. Best known for her work as The Seer, her illustration, video art, music and multimedia work draws on arcane symbolism, and is full of dark meditations on our relationship to the natural world. The character of Cassandra, alongside an interest in magic and an investigation into how systems of feminine wisdom have been suppressed, was one of her entry points into developing The Seer.

Her latest project, World Zero, is due to be performed at Birmingham’s Supersonic Festival this weekend, and bills itself as an immersive performance piece, an exploration of what new worlds might emerge in the wake of social and environmental collapse.

World Zero is both a product of Prantera’s restless and multi-layered creative imagination, and the result of a collaboration with militant performance collective UKAEA and video collective IMPATV. In the run up to World Zero, I spoke to Prantera at her home over Skype about her journey from the anarcho-punk scene in Rome to her current base in London, touching on moon rituals, lucid dreams, the importance of having dogs, and finding inspiration while driving down the M4.

I was wondering if we could start by talking about your artistic practice and how it’s developed. Am I right in thinking that you started out as an illustrator and you then got into video and multimedia? How did that come about?

Conny Prantera: I was a graphic designer/illustrator. I moved from illustration into fine art and realised straight away that the way most fine art was being shown was really limiting. I hated private views and I never got on with galleries because I wasn’t really trained as a fine artist. So I looked at the way that my friends in music were working and I found that much more inspiring. I come from a big DIY culture – the most influential band in my life was Crass. I’m from Italy, so I was in the anarcho-punk movement, the squatting scene in Rome. That was really formative. I really liked the DIY aspect of bands. They were creating a scene that seemed a lot more self-sustaining and exciting to me.

And you play music as well?

CP: I do now. I was classically trained, playing the cello. When I got into punk rock, I was only about 13, but I thought there was something really clunky about this instrument. The classical thing stopped me from enjoying being in punk bands because I was always worried I didn’t know the chords. I was quite shy and quite reserved, so working behind the scenes really appealed to me. I could be the creator of something but not necessarily the performer.

So that’s how you got into video?

CP: Yeah. I met Lisa Meyer from Capsule [curators of Supersonic Festival]. She asked me to do some illustrations for them, maybe the second year they did Supersonic. The following year, I convinced her that it was a great idea for me to do an installation. We just set up this room with my drawings and videos. I didn’t know how to make videos. I convinced everyone that I could do it. It was a really good first step into performance.

Could you talk a bit about The Seer specifically, the concept behind it? Were you drawing on any particular historical or mythological examples?

CP: I asked Lisa to do something else and I wanted to base it around the moon. I actually had no idea what I was going to do. But then I walked my dogs in the woods and decided it was going to be a moon ritual. It was the first time I went to Supernormal Festival. My partner’s from Wales, so we used to drive down the M4 every year. And at junction 11 there was this sign that says ‘The Oracle’. I became obsessed with this idea that if you were on the M4 and you wanted to see the oracle, you just had to pull over at junction 11.

And from then on I developed it. I got help from Lisa for funding and I realised that I wanted it to be a women-led project. There are a couple of men that are regularly involved, but I wanted to bring this really strong female presence to it. The project before The Seer was called Moon Ra. I was obsessed with the moon. But I didn’t actually know what a moon ritual was. I’m very instinctual in everything I do, so I’m not very good at researching things. I just pulled things together. And I’ve drawn on personal stories. I knew of this girl in my class who’d lost her sight. And I started researching the connection between losing your sight and seeing into the future.

Gaining other powers by losing one of your senses?

CP: Yeah. There’s a connection. The prophet is often either blind or unable to speak. Because I’m more versed in classical Greek and Latin history, Cassandra was my reference point. I really loved her. The archetypal mad woman who also holds the truth.

It connected a lot to the end of the world, which is present in so many aspects of our culture – in films, in writing. In 2012 everyone was very excited about the Mayan calendar. People have always had this idea of their generation maybe being the last. These days, every conversation you hear on the radio is like ‘these are challenging times’. I think if you put it in perspective, humanity has thousands of years of thinking society is on the verge of collapse.

Going back one step, you talked about feeling part of an underground, DIY type of scene. You were mentioned in a BBC radio series about ‘New Weird Britain’ and I wondered if that description resonated with you?

CP: I love what’s happening at the moment. I’m also a little bit protective of it, because it feels like some sort of secret. When I go out in London these days, I’m either playing a gig or being part of a gig. I feel like I’m in disguise a lot of the time. I know people have their normal lives and I’ve got this secret life that not everybody’s aware of.

At the moment, I’m working with UKAEA. We played at Supernormal and a lot of people started connecting the two projects. When I heard what they were doing, I fell in love and the first reaction was, ‘Let’s do something together.’ They’ve become family to me over the last six months.

You’re also playing with a band called White Horse Of The Sun. Could you describe your involvement with that project?

CP: That is David Terry of BONG and myself. We met last year at Woodland Gathering. He had just started playing the accordion, and we decided to play together. In that band I play cello. We’ve got a tape out on Opal Tapes. The tape was completely improvised, we never did more than one take. David’s the opposite of me. He famously said he only plays one note, so it stopped me from being impatient. There’s a famous Pauline Oliveros piece called ‘Horse Sings From Cloud’, and the score only gives two instructions: to change your note when you want to keep it and to keep your note when you want to change it. So your head gets really screwed up, you have to go against your instincts.

It seems like there’s a theme of ritual in quite a lot of your work. Is that fair to say?

CP: Yeah. I realised that I needed to frame this concept a little bit. I’ve been perceived as doing these very ritualistic performances, and I don’t feel comfortable with it because I think a ritual is something the audience has to adhere to and be part of. I like the audience to be part of something. But I also like the audience to be able to walk away.

The way I described it to my fellow performers was this idea that you create a dream, a fantasy – the whole idea of lucid dreaming, or being able to shape your dreams into something you want. People spend years in mental preparation for lucid dreaming, which is very difficult to obtain. So we’ve got this short cut, which is through art and performance.

World Zero live photograph by Elyssa Iona

You’ve talked a bit about some of themes behind World Zero. Could you give an overview of how you devised it?

CP: We wanted to give each other enough space to bring what we wanted. So we looked at Tarot and archetypes. We’re not imposing characters on anyone. If you think of Pina Bausch, the choreographer, she used to invite the dancers to bring very autobiographical aspects to the performance. She would set a series of questions and then build the performance around the material that had been brought to her. I think me and Charly [Blackburn, UKAEA’s art director], we’re doing something similar.

What’s the thing that you like audiences to take away from the performance?

CP: I’m drawing a blank! To be honest, because I’m actually performing in it, the idea of the audience scares me so much that I’m just like, ‘Forget about the audience.’ Most performances I’ve done, there’s always been one person that comes and says that it meant a lot to them. So if there’s one person that feels that way, that to me is enough. I don’t like the idea of entertaining people. My performances have become darker and darker. There’s a very downbeat element to it. I often feel quite sad and not everybody will want to be brought into that.

I wanted to ask you about that, because you deal with quite a lot of heavy subject matter in your work and I was wondering if that ever has a detrimental effect on your wellbeing? Or is your artwork and performance a way of channeling certain emotions and things you’re trying to process?

CP: I had kids very young, so part of my set up was to work on my art, but there’s also a daily routine that forces you to be present. You have to provide a meal and a happy environment for a family. I live in South London, where it’s very green. I’ve always had dogs, so part of my routine is always to be out in the woods nearby.

But I do feel a certain level of delusion at times. You become so absorbed in the character that you perform. I’ve got a collection of poems that I introduced into my performances. When you say a word with intention in front of people, it becomes so much louder in your head, to the extent that I’m walking around, repeating these words. It can be quite intense.

But I get the feeling that you’re optimistic. Even though we’re living in what feels like a time of crisis – political crisis, environmental crisis – do you feel that this actually presents a kind of opportunity for transformation, for renewal?

CP: Yeah, I guess so. I’m ambivalent about it. Most of my friends are way younger than I am. I fell in love with the new generation. I think people coming through into adulthood now are bringing something quite refreshing and new, and I love that energy. Maybe also for the first time there’s this disenchantment with the materialistic world. I think the collapse of capitalism is inevitable. And partly because people are getting over the material, everybody’s looking for other things. It’s becoming really absurd that we’re at risk of going extinct because we wanted more stuff. Do you really want to destroy the planet so you can go to the shop and buy more crap? I think the new generation are beginning to understand that.

The Seer, IMPATV and UKAEA present World Zero at Supersonic Festival on Sunday 21 July