I was never besotted with Morrissey. Had he swum into my ken a few years earlier, in my adolescence, I might well have been, since there is a perpetual adolescence about him. I was a student when ‘This Charming Man’ was released and watched The Smiths’ debut appearance on Top Of The Pops, the beguiling effusions of Paul Morley’s Single Of The Week review in NME dancing in my head as I did so. I enjoyed the way it swung both ways; on the one hand, he was clearly one of the great, queer gatecrashers to pop of the 1980s. Florid and flaunting his gladioli, big-shirted and swooning, he was a Romantic reproach to the tight-arsed, clipped, classical, peroxided hetero-pop of the day, from Nick Heyward to Nik Kershaw to Howard Jones. "New pop" had become slightly codified and cliched by this point. The dialectical wheel was due a big roll and The Smiths represented just that.

The Smiths were necessary. Unlike the Revolt into Colour of the 60s and 70s, from The Beatles and Stones to psychedelia and glam, The Smiths represented a 1980s counter-revolt into monochrome; the old, home truths of the black and white days, of Coronation Street, cobbles, kitchen sinks, Moors murderers and Vivian "Spend, Spend, Spend" Nicholson; back to the old jingle-jangle morning of fledgling beat music – that was actually quite radical and bleakly beautiful. In the mid-70s, pop had been a scarcity indeed, a merely weekly sliver of tinsel but by the mid-80s, it already felt like it was victim of its own surfeit, supersaturated; The Smiths seemed to hanker for the dank breathing space, the bracing desolation of a vanished yesteryear.

Yet The Smiths were part of a general, countercultural thrust. It was no more thinkable that Morrissey would align with the Right than he would wear a pair of Sta-Prest blue flares. No one in rock was, now. Eric Clapton had been buried for his pro-Enoch comments, Bowie spent much of the 80s making implicit and explicit acts of contrition for his whimsical flirtation with fascism in the 70s; the lumpen elements of Oi and Skrewdriver were absolute pariahs. It was a given that The Smiths were of the left; you didn’t even need to ask. There would be ‘Margaret On The Guillotine’, guest appearances at Red Wedge; moreover, Morrissey himself was gay, vegetarian, anti-monarchist, of Irish parentage.

And then, in 1986, Morrissey was interviewed by Frank Owen in Melody Maker and insisted that there was a conspiracy to maintain the presence of black music in the charts. He’d already remarked on the vileness of reggae, the awfulness of Diana Ross. Retrospectively, this should have been enough to hang him like a DJ but such was the goodwill he’d built up, that it was simply considered the first of what would be a long line of repeated cases of Bigmouth Strikes Again! Eyebrows were raised, but then eventually lowered. In any case, he would protest, he liked The Marvelettes and Dionne Warwick. Hmm. Black music was okay as long as it was nice and demurely antique, buried in the monochrome past rather than strutting impertinently into the present-day charts.

I myself turned frosty on Morrissey after this, though this was in part because The Smiths were slowing down as they wound down. Songs like ‘Girlfriend In A Coma’ seemed not to have much of a life beyond their titles. He was becoming risible, ripe for parody as an blousey Northerner trying to bring the values of Alan Bennett into the arena of rock and pop.

Only retrospectively did it become clearer that The Smiths had, indeed, represented a significant departure in post-punk history. Almost immediately after punk, post punk/indie had entered into an immediate and fertile dialogue with black music, yielding everything from The Pop Group, Cabaret Voltaire, A Certain Ratio to UB40, The Specials, The Beat, ABC, PiL, etc. The Smiths represented the point at which "indie" reverted to a depleted Caucasian-ness, the dreary spawn of which constituted most, of not all, of NME’s C86 tape. The dialogue with black music didn’t end but it was considerably lessened by the influence of The Smiths.

Then the split and, in 1988, Morrissey’s first solo album, Viva Hate. I reviewed it for Melody Maker and delivered a mixed verdict; I noted Morrissey’s complicated relationship with the past, in which every day was like Sunday. Then I came up against ‘Bengali In Platforms’. This, and later 1991’s ‘Asian Rut’, I deplored; I found ‘Bengali In Platforms’ possibly well-meaning but deeply patronising and utterly out of touch with the sensibilities of his very hip Asian fans. I knew. I was married to a Sikh woman at this time; her brother, Gurbir Thethy, adored The Smiths, subversively basing his dance at Sikh weddings on that of Morrissey.

As someone who had been chased through the streets of Birmingham for not being white, Thethy identified with Morrissey’s sense of being an outsider, both domestically and in society at large. "Morrissey was the voice that gave me a space to be the other. Someone who didn’t fit either at home or in the wider community," he recalls.

‘Bengali In Platforms’ was like a kick in the teeth from a man he had idolised; the scales fell from his eyes.

"What I didn’t think was that his (sometimes uninformed) literary allusions were a mask for his sense of elitism," says Thethy. "And that suddenly became writ large with ‘Bengali In Platforms” In 1988 I was 21 and overt racism was still the order of the day. The National Front was gone but only to be replaced by the BNP – and then this song happens. I felt betrayed. I felt like all the white boys I’d ever been "friends" with had only ever been a tolerance – that what they all really thought about me was summed up in this song. I was hurt beyond words. And his subsequent pronouncements have done nothing to prove me wrong. I no longer have any Smiths or Morrissey songs in my library. And never will."

Meanwhile, the dialectical wheel rolled on; rave, The Stone Roses, were part of a new, resurgent mass tide which swept the relatively tribal 80s away and left Morrissey, no longer a significant vanguard musical force, struggling for notoriety and attention. Hence 1992 and ‘National Front Disco’ and Morrissey, supporting a regrouped Madness at Madstock, wrapping himself in the union flag, a provocation to the abiding knot of far-right boneheads who had always plagued Madness and muscled their way to the front of their gigs. Morrissey would retrospectively be tarred with the racist brush for this gesture but at the time it also felt like he was playing sardonic games with English iconography; the way he had embraced ‘Suedehead’, a 1970s paperback hooligan in a clearly homoerotic manner. Seems something else was gestating, however.

Britpop happened but there was no starring role for Morrissey – it was as if he had been a stalking horse to weather the antipathy for reintroducing the union flag back into pop culture. Perfectly acceptable with Oasis, as his fans would groan with half a point. In 1995 he moved to Los Angeles. In 2005, talking to GQ, he agreed to the proposition that he had been "hounded out of England by the press" but as one of that beleaguered corps, it is hard imagine a scenario in which peak-capped members of the Fourth Estate surrounded his property, holding champing Alsatians by the leash and bellowing demands through bullhorns that he leave England immediately or face the wrath of a two star review for his next album in The Independent. But this is the sort of nonsense that can take hold in a person increasingly insulated from contradiction.

Through the Blair/Brown years Morrissey Morrisseyed along – he condemned Tony Blair with the same venom as he had Margaret Thatcher. In that same GQ interview, he said, "I think he’s atrociously bad for England and not remotely believable. But then British politics is always absurd, the most absurd people make advancements. There’s never anybody that you like and there’s never anybody that resembles you; there’s always a group of people who are devoid of scruples and absolutely do not speak for the British people. And we always believe there’s nothing we can do about it, which is beyond me."

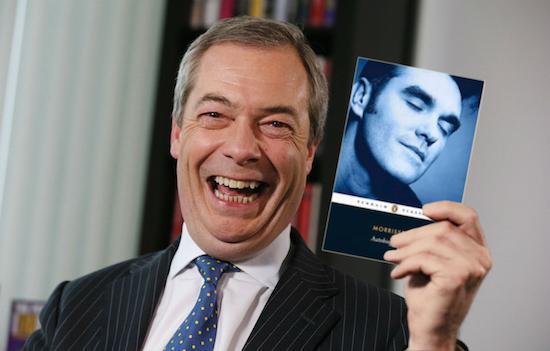

This is the sort of ambiguous comment which seems to invite an assenting nod of the head but could easily have been uttered by Nigel Farage. Similarly, ‘Irish Blood, English Heart’, in which he sang, I’ve been dreaming of a time when/ To be English is not to be baneful

/To be standing by the flag not feeling shameful/ Racist or partial/ Irish blood, English heart, this I’m made of /There is no one on earth I’m afraid of/ And I will die with both of my hands untied."

Ever since then, dog whistle by increasingly unsubtle dog whistle, living in splendid isolation from his home country and the consequences of his remarks, Morrissey has put himself beyond, and further beyond the pale. Decrying the unfair treatment of Stephen Yaxley-Lennon, aka "Tommy Robinson". Complaining to Tim Jonze in The Guardian about the "high cost" of immigration, in his imagination, to "British identity" as he conceived it from afar. Wearing a pin in support of far right group For Britain, led by anti-Islam activist Anne Marie Waters, for whom he has kind words – he rejects the "childish" label of racism; "I don’t believe the word ‘racist’ has any meaning any more", he has said, a statement only the most obtuse and whitest of white men could come out with. Most recently, after Stormzy’s triumphant Glastonbury headlining set, Morrissey shared a YouTube video in which some bloke attacks the rapper, using the headline "Nothing But Blue Skies For Stormzy … the gallows for Morrissey."

Sadly, he still has an ultra-loyal phalanx of fans, for whom the word "thickness" certainly does not apply to their skins, who insist that the "real bigots" are Morrissey’s critics demonstrating their "narrow-mindedness". Like their idol, they view of all of this as random persecution, in which they take a simple, indignant pleasure.

Persecution, persecution; the conspiracy goes on. A blog by one Fiona Dodwell complains of a sinister, longstanding, concerted Guardian-led "vendetta" against Morrissey, whose continued success they actively resent, having little else or better to do. Touching only briefly on accusations about his beliefs, Dodwell states that his high regard for Anne Marie Waters stems primarily from her veganism and the anti-Islam stance as a properly liberal response to the cruelty of Halal slaughter. "Are we really so uncomfortable with being provoked into thinking? Are we against even having the debate? So much so that we would rather silence or harass alternative voices?" We have it in for Morrissey because he is challenging our complacent, left wing views, discomfiting us with his daring proposition that we should embrace the far right; we sheep on the anti-Morrissey bandwagon dare not cross intellectual swords with him because we know he would best us with his maverick wit.

But it’s Morrissey himself who is wilfully, coyly selective about exposing himself to debate; he recently consented, for example, to be interviewed by his own nephew, opining that "everyone ultimately prefers their own race."

Dodwell is right in one respect; Morrissey still has many fans. Many profess to have no interest in his political views, regarding him solely as a musical content provider, a beat maker, a purveyor of vocals. This is bollocks, of course; they’re clearly hugely invested in him. In any case, if you’re capable of blithely setting aside his views, then there’s something badly missing in you. Morrissey has long since ceased to be worthy of cultural assessment; he no longer deserves to be part of that conversation. He has come to represent, along with the likes of Farage, Waters and Robinson, something nasty, reactionary and dangerous in our culture, a poisonous voice at this critical point in Britain’s island history. Something has hardened like a tumour inside him over the years; what was once whimsical, amusing, pop-culturally apposite, is now the stuff of disease. ‘That Joke Isn’t Funny Any More’ isn’t funny any more. He’s not rarified; far too many people think and feel the way he does. And they’re making less and less of a secret of it. It’s frightening.

And so, it’s come to this; with apologies to The Specials, if you have a Morrissey-loving friend, now is the time, now is the time, for your friendship to end.