There were arses everywhere. Male and female arses alike, pale against the green paint of the metal fence that darkened with urine, or sticking out from behind swamped portaloos and food stalls, pissing into the municipal grass. The bogs were overwhelmed but so were the bars that fuelled them, staff facing epic queues of angry punters who got to the front only to be told the booze had run out. By the evening of Field Day at London’s Victoria Park in 2007, things were not going well. Some punters left, others stayed, realising it was easier to buy drugs than a pint. They were to be rewarded. Liars appeared on stage in front of an audience equally divided between the absolutely furious sober and everyone else coming up on whatever they’d managed to scavenge from independent salespeople around the site. The twin drums of Julian Gross and Aaron Hemphill cut through the sweaty, muggy London air. Angus Andrew lolloped to the front of the stage, and screamed, all of that pent up frustration and quietly simmering MDMA fizz was instantly released, and the tent exploded, limbs everywhere. Just as they punished us with noise and rhythm, Liars gave an outlet, and created nothing but joy. It will always be one of the greatest gigs I’ll ever see.

It was the first UK festival gig Liars had done since the release of Drum’s Not Dead, their third album, the preceding February. There’d been smaller shows, at ULU, The Luminaire in Kilburn, White Heat at Madame Jojos (with These New Puritans, what a bill!) but this was the first time the band had been exposed to an audience that might not have featured those who had stuck with them despite the strange reaction to their second album. The unheimlich rattling of They Were Wrong, So We Drowned, released in 2004, had seemed to perplex critics and fans who preferred their the earliest incarnation as a party-friendly punk funk group lumped in with the Brooklyn scene around Yeah Yeah Yeahs, Strokes and LCD Soundystem. The mainstream music media in the form of Spin and Rolling Stone, still powerful forces back then, gave They Were Wrong their lowest possible marks, while Pitchfork sniffily wrote that “it’s not hard to not be popular”. Popmatters described the album as “painfully reactionary”. It was an articulation of the position Liars found themselves in then and arguably have ever since – too weird for the mainstream, too crackers and full of personality for the avant-garde. There appeared to be a general unwillingness to follow Angus Andrew’s command to “take your cauldron and get down” to comprehend the sheer visceral joy of screaming along “Fly fly there’s a devil in your eye shoot shoot WE’RE DOOMED WE’RE DOOMED” with this gigantic Australian over rolling drums. Their loss.

Lesser artists might have reverted back to where they found their initial success, but to their credit Liars (as they would continue to do up to the present day) doubled down. In retrospect perhaps the idea that Liars were constantly reinventing themselves was slightly overblown – it’s not like they were moving between ukulele folk and the blastbeat, after all. In 2006 Aaron Hemphill told Artrocker magazine that “Liars was very insular and always is” – there is a strong sense in the trajectory of not just the first three, but first five albums, that this was a band moving forward as a close unit without much concern with the musical world beyond their own boundaries.

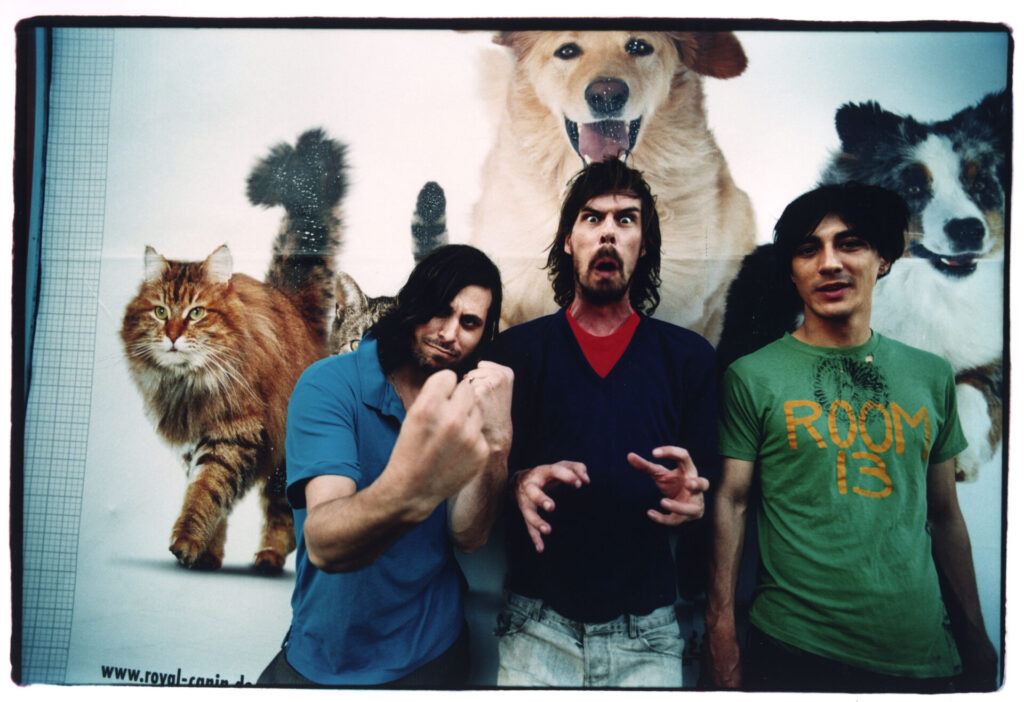

What many missed was how their experimental tendencies and embrace of noise and punishing rhythm was never tediously academic or austere. There was a loose madness to it all, the haze of bong paranoia and, live, astonishingly intense performance and a desire to put on a show. My memory is hazy, but I recall Julian Gross generally wearing a dress, Andrew sometimes all in white or in a shirt and tie below his long face, shaggy hair and moustache, like the accountant at a 70s porn cinema hiding out in the wilds from the mob and the taxman alike, mind disintegrating. Hemphill generally looked like a young rogue genius, too hot for science, directing matters, rattling out on a snare. At that Field Day gig and beyond they were brutal, visceral, hedonistic. Sometimes it was savage, but never antagonistic – his giant frame leaning over the audience, propped up on the mic stand, Andrew was shamanic, a leader, inviting us to join in Liars’ peculiar chant. And of course there was tenderness too. Andrew might have had a bellow on him, but he was always capable of a croon – and it was this is key to Drums Not Dead. Liars could write melodies, they just never saw them as the be all and end all, preferring to experiment with how they might sit in dialogue with the power of the drum, the instrument that was then the starting point for all the band’s compositions.

Drums need air, which is in part why Drum’s Not Dead was recorded in the rooms of an old Warsaw Pact-era Berlin radio station. Throughout Liars’ career, space and place has always been an important source of inspiration and practical shaping of their music. In that 2006 interview with The Stool Pigeon, Julian Gross pointed out that Aaron Hemphill had written a lot of the album in LA, and Berlin’s contribution was in cheapness and facilities, rather than a direct inspiration. It was different for Andrew, who in the same interview said that the German capital had been a shock to the system to someone used to living in suburbia, whether in New Jersey USA or as a child in Australia. “The music I started making when I got there was very solitary, and it kind of fitted this ethereal kind of place that I was living in,” he said.

The still extant Second World War battle damage and post-Cold War reconstruction created an atmosphere that he found jarring. “Parts of Berlin are like ruins,” he said. “These were things that have never been part of my vernacular before. I’d never experienced living, or writing, in that kind of climate.” He also said that as significant as being in Berlin was the expanding European Union, with an increased dialogue between the west and former east of the continent. There had been a clue to a new European art sensibility at this point, with the release of 2004 single ‘There’s Always Room On The Broom’, its cover featured the sigil figure logo of Einstürzende Neubauten, with a pointy hat and broom crudely drawn on. While Drum’s Not Dead had its sonic heritage in the likes of Neubauten, Faust or This Heat, this was a record by a trio moving forward by exploring interior landscapes and states of mind.

In Drum’s Not Dead, the thematic was more abstract than They Were Wrong‘s witches. The record was a dialogue between two characters – Drum, representing confidence and creativity, and Mt. Heart Attack, standing for doubt and anxiety. “This idea of the two characters is more to do with the inspiration behind the songs, rather than a through-line that weaves the album together,” Hemphill told The Stool Pigeon. Andrew was more specific, saying to Artrocker that the characters were representative of mania and depression, and the human tendency to lurch between them. He described them as “illustrations of the battle within everyone… the duality that particularly relates to the creative process.”

The dominance of the drum in this album, then, represents the constancy of the human heart despite the tricksy unreliability of the mind. “Drums have always been the starting point, and I think that’s based in the idea of lacking musicianship,” Andrew told Flux magazine. “Most of the time it was like, let’s make a hip hop song, and then the failure would be the Liars song.” Perhaps this is what makes this record so strong, that by consistently failing to be something else, Liars could only ever be themselves. Where you can listen back to so many records that exist in the hinterlands between experimental music, rock, indie, and noise and find that over time they’ve become stale and arid, Drum’s Not Dead remains animated and intense.

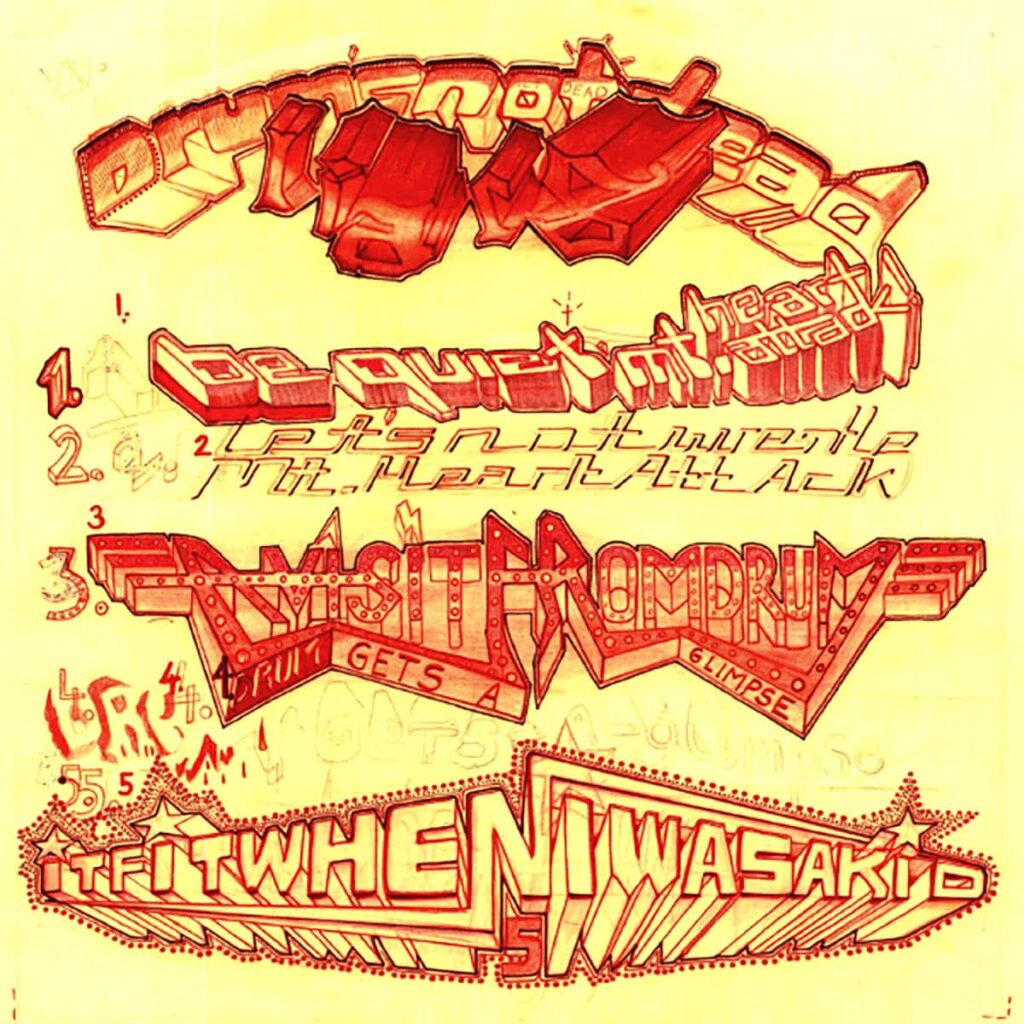

The drums are recorded dirtily, from the first, stentorian repeated rhythm on ‘Be Quiet Mt. Heart Attack’ onwards sitting in a mix that’s full of echo and air. Drum and Mt. Heart Attack chase Liars around the corridors of that old radio station and for all the pranging heaviness, metallic distortion like taut aerials protesting at the propaganda nonsense they were once forced to broadcast, Drum’s Not Dead‘s noise is only half the story, just as was the heaviness of their gigs. The guillotine march toms and restraint of ‘A Visit From The Drum’ give way to the watery shimmer of ‘Drum Gets A Glimpse’. It’s followed by ‘It Fit When I Was A Kid’, tellingly the only song without Drum or Mt. Heart Attack in the title. The initially panicking menace and lurid bad trip lyricism breaks down into something softer – Drum’s Not Dead is never binary, Andrew’s vocal conveying a multitude of moods within each song. “I will remember you,” he sings gently. Most human minds blur between states, rather than snap, after all. Final track (still Liars’ most-streamed) ‘The Other Side Of Mt. Heart Attack’, is in one sense a perfect lullaby, Andrew singing, “If you need me / I can always be found”, amidst ooohs and aaahs. It could either be a salve for a tortured mind, or ironic – anxiety, dread and bad patterns are always waiting, paradoxically a place of familiarity that we can’t help tapping back into in moments that meds and therapy alike can struggle to deny. It’s worth noting that the three films that came on a DVD with the album release, by Gross, Andrew and Markus Wambsganss, give Drum’s Not Dead a new lease of life. I can’t be alone in not having a DVD player back then, and in any case being too out and out of it to have had time to sit with them. Now, in the age of YouTube, you happily can, the intricate animations opening up new avenues into the record.

After Drum’s Not Dead, Liars would continue to shapeshift within their own parameters. Follow-up Liars (2007) was a successfully exuberant attempt to make a straight-up thrashy rock record. Sisterworld (2009), arguably Liars’ masterpiece, was a searing, violent dissection of utopias, or Los Angeles yuppie hypocrisy, depending on how literally you wanted to take it. Gross and Hemphill left after Mess (2014), leaving Liars as a solo project of Angus Andrew alone. Sonically, both this later version of Liars and Hemphill’s criminally under-regarded Nonpareils project are loaded with the ripe DNA of what made their astonishing run from They Were Wrong onwards arguably the greatest of any US indie rock group of our century. Yet Liars somehow remain a relatively cult concern, beloved of a devoted hardcore, lacking the wider recognition of their more conventional peers. In their lack of wider commercial success I see a story of what the leftfield music scene, industry, whatever you want to call it, could have been had the money not fallen out of the market. Look at Liars’ ancestors, especially those on Mute, your Neubautens and Bad Seeds – they would never be able to follow the same kind of cult yet sustainable career path as those artists have enjoyed.

Late last year, footage emerged on social media of Andrew, Hemphill and Gross smartly dressed and bashing out Liars songs at the drummer’s wedding. It looked like a joyous moment for the trio, perhaps because it was a one off on a special day, not to be repeated. Watching on my tiny phone screen, I had a rush as violent and beautiful as I did when they saved Field Day nearly two decades ago. Much as I’ve no time for nostalgia touring, do feel like this collaborative iteration of Liars have unfinished business, and it did make me hope that perhaps there’s still life in the old drum, after all.