In October last year the musician Angeline Morrison, whose 2022 masterpiece The Sorrow Songs drew on deep research to present new folk music that centred the real Black British figures who are often written out of history, was invited to curate an all-day programme at Cecil Sharp House – the headquarters of the English Folk Dance and Song Society. It was a night of many highlights. She lights up as she recalls the singer-songwriter Muco setting Old and Middle English to inanga (traditional Burundian zither), and the Haitian traditional tunes performed by Germa Adan – among many other performers – as well as onstage conversations with the broadcaster and writer Zakia Sewell and the Obeah practitioner and morris dancer Emma Kathryn. The part that will live longest in her memory, however, was an informal folk club held in one of the building’s basement rooms.

“I’ve had this dream in my head for years of a global majority folk club,” she continues, “so I asked people to bring instruments and some songs to share.” It outstripped expectations. “It was just so moving, it was extraordinary, like no folk club I had ever been to, because folk clubs are always majority white. Somebody sang a song they’d written about trespassing through people’s gardens at night. Somebody sang a lullaby that their Ghanian mother used to sing to them at night… It was incredible.”

That night was one of several foundational moments (although as we shall see, it was not the first) that fed into the creation of the Black British Folk Collective, which launched last month. Morrison is one of three core members, alongside Marcus Macdonald – who comes from a squat punk background and is also one of the figures behind Land In Our Names, a reparations and land justice collective for Black people and people of colour – and Bianca Wilson, a musician in both the experimental project Calliope (who also performed at Morrison’s takeover) and The Pegwells, who play old time Appalachian music.

When I ask the three, who speak to me over Zoom, to describe the BBFC’s aims, Morrison puts it as follows. “We are a group of people seeking to highlight all the contributions made by Black folkies in Britain, and create a virtual community for all of us to raise awareness of historic Black contributions to folk culture and presence in Britain.” On the equinoxes and solstices this year, they’ll be hosting folk clubs across the country (details can be found at the end of this article), and are hoping that it’ll encourage others to do the same. “After Cecil Sharp House, people kept coming up to me saying ‘are you going to bring this to where I live’. It hit home how much of a desire there is for this,” Morrison continues.

Another key part of the BBFC is using their growing public platform to spotlight not only the Black folk artists operating in Britain today, but historic Black contributions to the country’s music and culture. They have already featured Billy Waters, a busker in Regency London who was well-known in his day, John Blanke, a trumpeter to both Henry VII and Henry VIII, and Dorris Henderson, a key fixture of the 1960s folk scene in both Britain and the US, among others. “We don’t have to make it up, these people existed, and are a part of the tapestry of British history. There’s an authenticity to the identity of people of colour that also belongs to Britain,” says Wilson.

Adds Morrison: “The historic element is very important, because the history that all of us are miseducated with does not include the Black ancestors who we know were present in Britain for over 2,000 years. When people talk about folk music, it’s associated very closely with a place or nation, but the folk music of England is very much associated with whiteness. Obviously, England is a white majority country, but there’s always been a presence of Black, Brown and global majority people here, through trade, through travel, and many reasons that are completely separate from the transatlantic slave trade and the Windrush – the two things in popular consciousness that Black people in Britain get associated with.”

The first seeds of the BBFC were sown in May 2024, when Morrison and Macdonald met at a dinner organised by Chardine Taylor-Stone – former Big Joanie drummer and a member of Border Widow, who would go on to play Morrison’s takeover – who thought it would be important for Black folkies to meet before a show, also at Cecil Sharp house, by Femi Oriogun-Williams, also a member of Calliope alongside Wilson. At the dinner they spoke a lot about the context of Black folk musicians performing at a site bearing the name of the towering Victorian folk song collector, given how often, as Macdonald puts it, Sharp “left Black and people of colour out of his research, and out of the archive.”

Morrison notes that when Sharp travelled to Appalachia in the 1910s in the belief that English folk song could be found in its “purest” form in isolated mountain communities untouched by the wider world, although he did collect from Black singers he also failed to engage with the way English folk songs were flourishing across wider Black communities. “He just left them, because it didn’t suit his idea of what English folk song should be,” Morrison says. “Which is completely in keeping with the way that Black musicians in the history of British folk music have been erased.”

“The way people still believe that there weren’t Black people in Britain until the Windrush,” adds Wilson. She was sound checking for a performance with Calliope so missed that dinner, but remembers how similar conversations permeated the wider event. “We felt like we had to say ‘No, we are British, this is Britishness as well. This multitude of faces all exists within the umbrella of Britishness. There’s no person that belongs to this land more than anybody else, because people have been in transit forever.’”

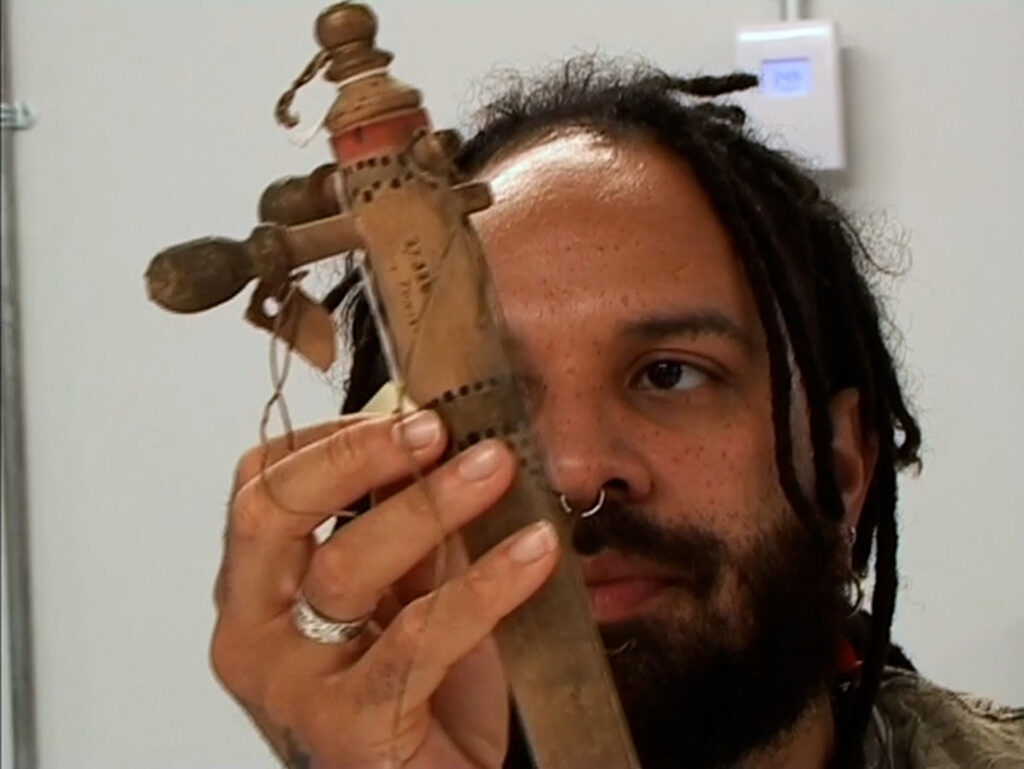

Early the following year, Wilson and Macdonald were invited by Carey Robinson, the head of learning and participation at Cambridge University’s Fitzwilliam Museum, who was familiar with other work that the pair had done together, to take part in a programme called Future Legacies. They were invited to use a piece from the artist Barbara Walker’s Vanishing Point series – which takes classical paintings featuring Black figures, usually servants, enslaved people or attendants, and reworks them to make those figures the focus – as a jumping off point for a wide-ranging discussion on resistance. Bringing Morrison onboard after that, they went on to receive funding from Cambridge’s ‘community-led research’ fund for a project called Crossing Continents: Collections Research As Resistance, from April to July last year.

Threaded throughout the project was an idea, Macdonald says, of “retracing the journey of the banjo from West Africa to the plantation in the Caribbean, to the American South” – something that’s been core to Wilson’s work for some time.“That instrument has had some highs, and it’s also had some serious lows, some really, really dark stuff,” she explains. “So, it feels really significant to re-establish the connection to that instrument and where it comes from, reappropriate it out of not just more modern racist connotations, but things like the minstrel movement that was incredibly popular from the mid-19th century until the 1960s; that’s 100 years of racist entertainment where the banjo became a core piece of symbolism. We’re trying to heal from that and take it into a future that is more positive and that will exist longer than any of us do.”

As well as gaining access to Sharp’s archive, the three were allowed into the collections store used by the Fitzwilliam, as well as the University’s Museum Of Archaeology and Anthropology among others, which is kept in a bunker built in the 1950s, originally to house a military government in the event of a nuclear attack. “They have over 350,000 stolen objects, items belonging to African people, including human remains,” Macdonald remembers. “Our project was all about looking at these things from the diaspora and bringing what we found back to our community.”

As well as gaining access to Sharp’s archive, the three were allowed into the collections store used by the Fitzwilliam, as well as the University’s Museum Of Archaeology and Anthropology among others, which is kept in a bunker built in the 1950s, originally to house a military government in the event of a nuclear attack. “They have over 350,000 stolen objects, items belonging to African people, including human remains,” Macdonald remembers. “Our project was all about looking at these things from the diaspora and bringing what we found back to our community.”

“Us being in the archive was also about disrupting the traditional status quo,” says Wilson, “thinking about how power is exerted through ownership of possessions. Who gets to tell history? Who gets to hold the artefacts, and render these spiritually and culturally significant things into objects that get kept behind lock and key? Being there, handling those things, being able to talk about it and have a physical connection, felt like it was disrupting that power.”

Morrison was particularly drawn to musical instruments held in the archive. “We were allowed to handle them and play them. I found that so moving, because I feel like each instrument holds imprints and vibrations of all the ancestors who’ve played it before you.” In these instruments, she says, were powerful physical manifestations of what draws her to folk music as a whole, the way it evokes “invisible hands of the ancestors stretching back further than anybody can see. You’ve got the same things in your hand for a moment, you’re handling this precious musical tradition that’s come to you for a bit, you can breathe your essence through it, make it your own, and then it goes on to other people into a future that you will never see.”

Exploring the archive was not an easy process, the three stress. At one point towards the end of their time there a manilla – a horseshoe-shaped piece of metal used as currency to purchase enslaved people – fell out of a box in front of them. “It was horrific,” Macdonald says. “Really, really upsetting. Although one thing I would say is that the people who are stewarding the space were amazing, really understanding. They’re workers, they don’t represent the institution, but we had good conversations about repatriation of these objects, how they would love to do that but often there’s nowhere to bring them. I felt OK leaving, because I felt like they were handling everything with care and love.”

Morrison composed a ritual for those whose remains were stored in the bunker, in which Macdonald and Wilson took part. The project also led to two programmes broadcast on NTS Radio, a folk club, a short film, as well as a social gathering in southeast London at the Land In Our Names community garden. And yet, prolific as they were, the group also felt that they were still just scratching the surface. More than any other point, Macdonald says, Cambridge was “a big uniting force for us to start the BBFC. We kept talking about a Black folk revolution. The project was hard at times, some of it was quite traumatic, but as we were doing it, we felt like we really needed to keep this work going.” In September they applied successfully for funding from the Ffern Folk Foundation, and launched the BBFC formally via social media at the beginning of this year.

The BBFC has, on the whole, been received with positivity, although Wilson points out that “we’ve also already experienced resistance, and it feels like that is just the beginning.” There has been targeted trolling on their social media accounts, “and I’m sure there will be more.” They anticipate backlash in the right wing media, too. “People need to understand that that is part of what it means to speak as a Black person or as an ethnic minority in a white majority country. It’s really important to highlight that a lot of people are deeply uncomfortable with the work that we’re doing.” Painting the Black British Folk Collective as a feelgood story, Wilson continues, “doesn’t give the full picture of what it means to be disrupting the hierarchy of power, and how offensive that can be to some people.”

And yet, the BBFC’s importance as a point of unification cannot be understated. “One of the things that I keep noticing about Black and Brown people doing folk stuff in Britain is that there’s actually a lot of us, not just music but singing, dance, folk spirituality, folk medicine, folk growing practises and more,” says Morrison. She looks back to a photograph, taken on the evening of Femi’s Cecil Sharp House performance, where a number of those involved arranged themselves on benches in a playful imitation of a school photograph. “All these Black folkies uniting at Cecil Sharp House… there was such a feeling of excitement,” she continues. “Just about how many of us there were, and what might be possible if we get together.”

The Black British Folk Collective will be hosting folk clubs for the Spring Equinox (26 March) in London with the venue TBC, and the summer solstice (20 June) in Manchester at The Peer Hat. The autumn equinox will be marked in Glasgow with the specific date and venue to be confirmed, and the winter solstice at Cecil Sharp House in London (date to be confirmed).

Read on for reviews of winter’s folk releases

Elspeth Anne, Côr Meibion GwaliaBetwixt & Between 12Betwixt & Between Tapes

The 12th installment of Betwixt & Between, a series masterminded by Jacken Elswyth (extraordinary banjo player and member of Shovel Dance Collective, The Greater London Banjo Trio and more), which sees each cassette split between two artists working in traditional, improvised, drone and/or ambient music in an effort to explore what resonances and contrasts can be made between them, is to be the last. Released on 8 December, the final edition is themed around Christmas and New Year, which makes its inclusion here a little out of date, such are the whims of the publishing schedule. That said, this closing statement is such a gem, and the series as a whole has been so foundational to my listening over the last few years, that I hope you’ll forgive me a little temporal dissonance.

Side A is given to the Herefordshire multi-instrumentalist Elspeth Anne, who begins by establishing a haunting and warped weave of cracked organs and a modest keyboard, set the babbling flow of water, on which we’re carried into a piercing performance of the Appalachian ballad of loneliness ‘Cold Mountain’. Mangled just slightly by lo-fi production, her singing is transfixing, even more so when an insistent drone that has been ebbing and flowing beneath is cut for the final minute to leave only that voice. A field recording of hailstones on Ynys Môn then cuts the silence, hammering all around as the musician shifts into ‘Coventry Carol’. Here the vocals are warped that bit further, now shuddering with deep intensity. The hail pounds harder and harder until it is almost suffocating, whereupon a thicker drone emerges to up the dread that little bit more. Then, something shifts. On the outro the hail transforms into rain, Anne unspooling a circular melody on reed organ that feels like a refuge from the elements – still stark, but comforting too, like campfire to start drying off the damp.

Side B, meanwhile, features the Côr Meibon Gwalia, an esteemed male voice choir, joined by the London Northumbrian Piping Group. Both collectives have been active since the 1960s, and though the material here was recorded last year, the hymns and wassails they perform sound as if it could date from any point along that timeline. While Anne’s side plunged the listener into an uncertain emotional space where nature’s beauty and brutality intermingles, the tape’s second half brims with a deep, rich, and uncomplicated sense of warmth. It is staggeringly beautiful, and a fitting close to what has been an essential series.

NIMFSirenoscapeCursed Monk / Fiadh / Camellia Sinensis

In my view, to perform a traditional song or melody with proper power is to channel it directly through your own immediate experience, and to apply it to the here and now. In doing so, you are not cosplaying those who will have sung the same in generations past, but providing those people’s actions with a real contemporary resonance. Just as you are using old words to apply to the blooming, buzzing confusion of now, it hammers home that they too were they using them to apply to the blooming, buzzing confusion of their own; they emerge as real multi-dimensional people. At the same time, it invites you to consider those who will sing the songs after you are long gone, what unguessable resonance they might find to apply to their own lives. It’s this that makes folk music, whatever its surface sonic qualities, a deeply psychedelic thing. Multi-temporal as much as it is timeless, capable of putting past, present and future on equal footing and pulling at the seams between the three.

One of the things I like about Sirenoscape, the new album by Irish-born, New Jersey based Aoibhín Redmond, is that she places her material – four lengthy pieces, which she calls ‘scenes’, where traditional and self-penned tunes, ballads and invocations emerge and fade into widescreen soundscapes – in very distinct settings. This is partly thanks to close collaboration on visuals and design with the filmmaker Alexander Kuribayashi. ‘Invocation Of Plagues’, for instance, is set deep in a forest, where we hear the patter of rain and the crashes of thunder. ‘A Ballad For Looking Into Time’ is set to the crackle of a campfire. The opener, ‘Solar Excess Sacrificial Ecstasies’, by its use of ‘Willie O’Winsbury’ and ‘Summer Is Icumen In’, performed to directly evoke the climactic sacrificial parade at the end of The Wicker Man, takes us through the threshold between fact and fiction, and back to Summerisle.

The depth with which these scenes have been established is highly impressive in itself, but they’re really just the record’s framework. Instead of static aural landscapes, NIMF’s hallucinatory music is heavily layered and constantly shifting in tone and timbre, meaning that it teems and lives and breathes – sometimes to the extent that it frays at temporal and diegetic edges. If folk music done well can put past, present and future on equal footing, here is an artist who revels in blurring the boundaries between those states.

Florian Nastorg, Vincent RousselStill Life With Sausage SplitCaresse

I’m regularly astonished by the traditional music coming out of France, so much so that when prepping this season’s column, I thought I’d type ‘expérimental traditionnel’ into Bandcamp’s search bar and see what came up. Immediately, the second side of this split cassette caught my attention, where Vincent Roussel lays down a terrific warbling pipe that fades into a mangle of field recordings and noise, distant chants, then swoops back up to a pounding ritualistic rhythm. Then there’s a flitter of a whistle, a crash of drums and a buried rendition of two traditional songs, ‘Marguerite Elle Est Malade’ and ‘Aquesta Annada’, until the pipes return for a final flourish.

Obsessed, I got in touch with Roussel for more information. “I am a drummer and improviser involved in experimental music as well as traditional music from my region, Occitania,” he told me via email, explaining that the pipes he’s using are a rare kind, specific to a small region near the Pyrenees. Occitan culture, historically repressed by the French state via systematic marginalisation, forced linguistic assimilation (before French schooling was made compulsary in 1860, native Occitan speakers represented more than 39% of the population, but has plunged to between 3 and 5 per cent today), is particularly important to him, he says. “For me, this is political.”

While we’re here, though the manic blend of radio samples, jazz, crust punk, high tempo dance beats and uncategorisable noise that constitutes side A seems to have little to do with folk music (unless you want to get into the ‘what is folk music’ debate, which I don’t) – I highly recommend that too.

Canes Of KarabakhCanes Of KarabakhCrossroads Centre

Canes Of Karabakh is a new project from members of Polish outfit kIRk, whose Stanisław Matys has recently been studying the duduk, an Armenian woodwind instrument that some scholars claim has existed for 3,000 years., and which produces an intensely haunting sound. The highest quality reeds for the instrument are made from cane sourced from Nagorno-Karabakh, a region that has endured a turbulent recent history. Having been governed by ethnic Armenians under the breakaway Republic Of Artsakh since a war between Armenia and Azerbaijan in 1994, in 2020 a second conflict saw the latter launching an offensive that saw them take significant territory around the region, leaving Nagorno-Karabakh itself as a rump state connected to Armenia only via a narrow Russian-controlled corridor. In September 2023, a Russia-brokered ceasefire collapsed, and Azerbaijan launched a fresh offensive, dissolving the republic a few months later. With 100,000 ethnic Armenians fleeing in the aftermath, several international experts have accused Azerbaijan of ethnic cleansing and war crimes.

One of the knock-on effects is that, according to Matys’ Armenian friend Narek, who has been teaching him the duduk, those reeds are getting increasingly scarce and have doubled in price. Though it might appear a trivial consequence, to me there is also something particularly powerful in the fact that it should manifest in this way – the fate of a wider culture reflected in its ancient instrument. For the Polish musicians, it also raises uncomfortable questions. In accompanying press material they are open about their discomfort over their means to afford the reeds while many Armenians cannot, and that Canes Of Karabakh is drawing deep from an endangered tradition that is rooted in a people and place that is not their own. On the record they have therefore purposely avoided traditional melodies, “feeling their great importance, which we cannot fully honour,” instead focusing on the dubuk’s unique timbral qualities, taking that haunting fragility and blending it with flugelhorn, trumpet, electronics and field recordings into a rich and meditative new work. It is – and should be – up for debate how much a band can do justice to a culture that is not their own, but it is to the trio’s credit that they leave themselves open to that discussion, and that their intentions are evidently pure. On purely sonic terms, too, this is an engaging and frequently beautiful record.

Adam WeikertThe Gleeman Guild

There are so many artists now exploring English and British identity via folk music, that when an album by the then-unknown to me Adam Weikert that professed to do the same landed in my inbox, I’ll admit that I was cynical. Then I pressed play on the first track, ‘The Merry Death Of Old England’, and felt my jaw clench, my skin bristle, my cerebrospinal fluid start to boil – blast after blast of squalling chanter, each raging like the ignition of a flamethrower. There are many trying to articulate the sheer havoc of modern existence, but few with the kind of fervour heard here.

Elsewhere there are subtler expressions of a jumbled modern existence – that piece, for instance soon fades into a far prettier rendition of the traditional Irish reel ‘The Princess Royal’, specifically a version from after its migration to Abingdon, close to where Weikert was raised, set to a blend of field recordings from the ocean and a Leicester Wetherspoons – but that rage returns throughout. ‘Ah Cud Hew’, written by the County Durham musician Ed Pickford about the death of his father from pneumoconiosis caused by inhaling coal dust while working in the mines, is set to an unnerving lurch of thuds and scrapes (partly produced by a sheng, in an effort to draw parallels with similarly brutal working conditions still in existence today around the world. ‘Greensleeves’ stays on that post-industrial theme by taking performing the old tune with the ghostly scrape and warble of a saw harp made of Sheffield steel, intermingling it with a field recording from the Heights Of Abraham cable car that now ferries tourists over an abandoned mine. The chanter returns to warp ‘God Save The King’ into deconstructed dissonance – inspired by Weikert’s learning that many NHS institutions are still forced to pay rent to the Royal Family. A slow and pensive closer ‘Farewell To The Green Man’ is inspired by a folktale about green-skinned children speaking an alien language, its obvious allegory for immigration hammered home by the incorporation of news clips declaring their horror at refugees arriving by small boat, layered a hundredfold so they are a babbling mess. Compared to many of the others drawing on themes of fractured Britishness in folk music, this is among the more straightforward in its message, but Weikert proves that sometimes the direct approach can be the most powerful.

Magda DrozdDivided By DuskPräsens Editionen

To call Polish musician Magda Drozd a violinist feels like an understatement. On Divided By Dusk, she takes the instrument and stretches it out into an album of remarkable scope. It was partly inspired by Drozd’s time in Japan where she collaborated with two members of the experimental band Goat, producer Koshiro Hino and Rai Tateishi, the latter of whom provides shinobue (bamboo flute) and khaen (mouth organ) to the noirish ‘Rounds’. Though she draws on the traditional music and folklore of both Japan and her native Poland, for the most part this is done subtly, as one strand in a complex weave that ends up more as a thick cut of dark ambient, evoking ritualistic airs but without specificity. On its centrepiece ‘Piosenka Ludowa’ however (Polish for ‘folk song’), her violin suddenly soars out shimmering from the gloom, cycling around and around on a single folkloric motif, all the more glorious sounding for all the murk that surrounds it elsewhere. Afterwards we plunge once more into the dark until at the record’s very close, ‘From The Depths’, Drozd draws directly on a Polish folk motif deconstructing and reshaping it so that its ancient power somehow increases.

BarrenBarrenSelf-Released

I don’t know much about Barren, a self-titled record I found trawling the depths of Bandcamp, other than that it is the project of Manchester-based Joey Francis with producer Matt Tulloch. The former (who an Insta stalk reveals to also be a talented poet) replays bodhran drum, which the pair then mangle, fray and manipulates it through pedals and experimental production. There are also purrs from Frank on ‘Wild Garden’, who I assume to be a now-departed cat, given that one track is billed as his lament. On first listen, Barren appears to be basically just harsh noise bodhran – which is a great thing, obviously – but closer attention reveals surprising depth. Francis’ drumming flits between several modes – sometimes a relentless rhythmic pound, sometimes a lolloping lurch, sometimes skittering chaos – which the production constantly pushes into some deeply strange territory, whether synapse-frying feedback, bubbling dark ambient, or – on album highlight ‘No Notes’ – a magnetic bassy groove. Comprised mainly of short little snippets, final track ‘Minorie’ is an epic by comparison, with Frances performing the Child ballad also known ‘The Two Sisters’, his voice uneasily skipping in pitch to the sound of birdsong and a clenching feedback drone. The more I listen to this record, the more I love it. Also worth flagging is that all proceeds from this pay-what-you-want release are donated to the Sameer Project, providing aid to displaced families in Gaza.

Jon WilksBonesSelf-Released

Jon Wilks has been one of the driving forces in the London folk scene for some time, not least as one of the people behind the mammoth Martin Carthy spectacular that I wrote about in the last edition of this column. Bones, he tells me, is like his Hatful Of Hollow, a Bandcamp-only compilation of various live recordings, demos, offcuts and B-sides from a prolific last few years. It is, admittedly, not the kind of music I usually cover in this column – Wilks stays closer to folk music as a finely hewn craft than as means for experimentation – but that is not to diminish its quality; Wilks is among the best at what he does, his guitar playing wonderfully sharp and shimmering. I’ve made an exception purely thanks to a point where Wilks and special guest Graham Coxon let loose to remarkable effect during a live recording of ‘Scarborough Fair’. Of all the songs in the folk canon, it’s probably the most charged, the kind people with no other knowledge might sing in mockery of an old-school folky, but thanks to a blistering electric guitar solo (which Wilks accurately describes as an aerial bombardment from the folk gods themselves) it is here transformed into something remarkable.

PefkinUnfurlingmorc

Pefkin is the solo moniker of Gayle Brogan, a member of Burd Ellen – one of the artists pushing folk music into radical climes long before it came back into vogue – and the psych-inclined Electroscope. Unfurling is her fourth solo LP and aptly titled – here, indeed, is music that unfurls from the very start. Inspired by the gradual yet profound change from winter to spring, the record begins with echoing violin that sweeps languidly over a sparse rhythm, mingling with Brogan’s vocalisations, swelling gently in volume until the atmosphere darkens like gathering clouds. On ‘Sun Flecks’, twittering birds are set against electronics that float like mist above melting frost. ‘My Breath The Sea’, meanwhile, is inspired the Irish saints who once crossed to Scotland via primitive bowl-shaped boats called coracles, to live as hermits on isolated islands, Brogan’s voice drawn close as if echoing off the walls of a cave.

Kelby ClarkLiving MemorySound Holes

Georgia-born Kelby Clark last featured in this column almost exactly a year ago, with an excellent collection of improvised clawhammer banjo called Language Of The Torch. Where that record was largely acoustic, on new release Living Memory he’s gone electric, presenting two suites that use traditional music as a jumping off point for improvisational work that bubbles and brims with warped and understated intensity. It’s not quite a yin to the first album’s yang, there’s a distinctive snaky flow to Clark’s playing that carries through both releases, but they do make fascinating companion pieces.

Oberkas TravelTańce

A third and final Polish entry to this year’s Radical Traditional comes via a brief mention for this utterly delightful take on folk music from the country’s centre, particularly the Radom–Opoczno region where oberek – a folk dance defined by its quick pace, lively energy and spinning moves – is deeply rooted. Oberek Travel take the distinctive triple-metre music that accompanies oberek as their starting point, weave in little psychedelic manipulations so that the style’s inherent hypnotic power is amplified rather than diluted. When the esteemed Polish folk singer Maria Siwiec is brought in on occasional guest vocals, it resonates more powerfully still.