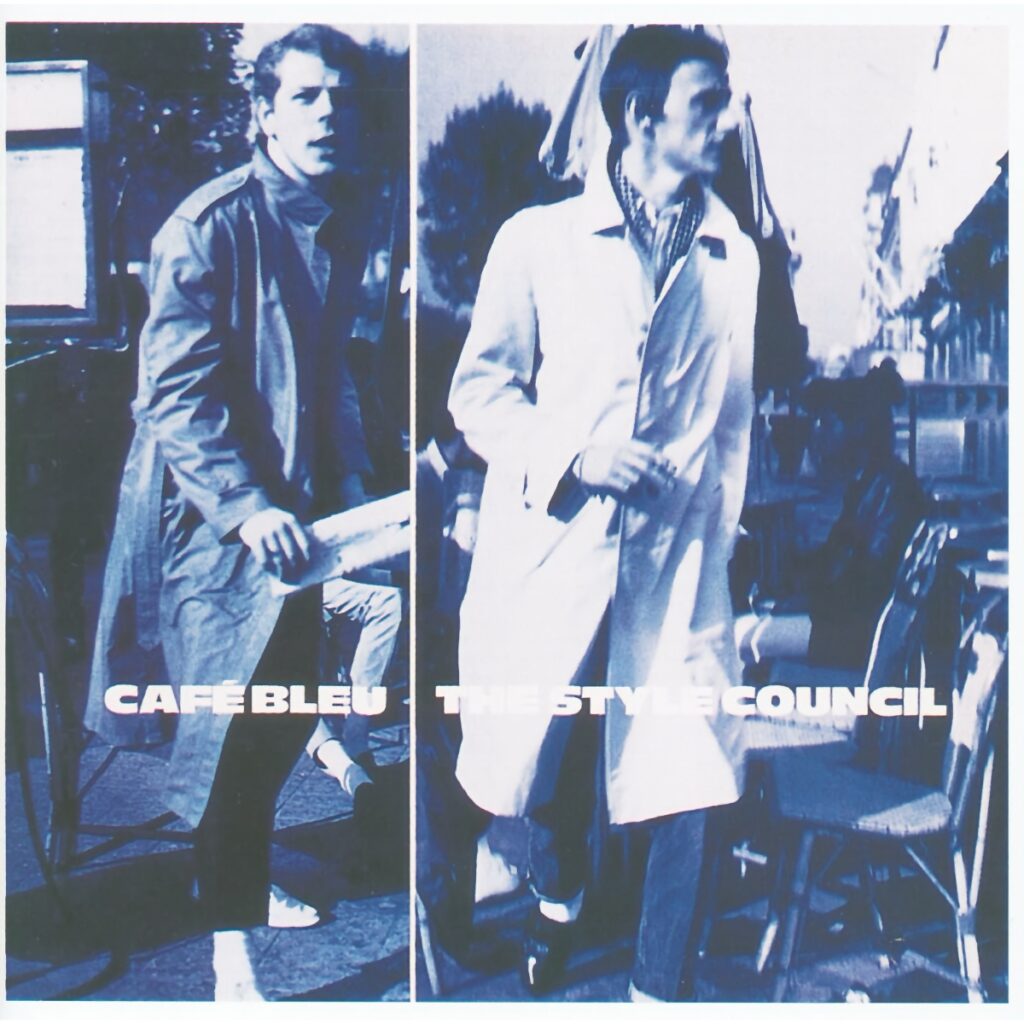

Imagine it’s Friday 16 March 1984. The National Union of Mineworkers declared a nationwide strike on Monday and you are ringing in the weekend with Café Bleu, the new LP released today by The Style Council. Something’s off, though: by the start of the tenth song on this record, you have heard Paul Weller sing lead vocals on only two tracks. This is, presumably, confounding.

Instead you have heard four instrumentals of varying genre, from a jaunty piano boogie led by Mick Talbot (‘Mick’s Blessing’), to whimsical bossa nova (‘Me Ship Came In!’), melodramatic guitar jazz (‘Blue Café’), and frenetic Blue Note-style bop (‘Dropping Bombs On The White House’). You have heard what appears to be an Everything But the Girl song (‘The Paris Match’) whose own debut album isn’t even out yet. You have heard a rap song too (‘A Gospel’), performed, not by Weller – nor any other white punk such as Debbie Harry or Joe Strummer – but Dizzi Heights, a full-time practitioner of the adolescent form. And you have heard a Prince-like electro-funk number (‘Strength Of Your Nature’) whose single lyric Weller repeats over and over again with Dee C. Lee, whose move from back up to foreground vocals will eventually ensure The Style Council becomes something grander as time progresses.

The new deluxe edition of Café Bleu is a welcome reminder of just how audacious the early Style Council was, how eager to put the public on its back foot. Predictably, Café Bleu was dismissed by some critics as an exercise in genre tourism. Its eclecticism is conspicuous but not that strange, given the direction Weller had been signalling since at least ‘Absolute Beginners’ (1981) and the ‘Town Called Malice’ / ‘Precious’ double A-side (1982). It wasn’t a leap from Diamond Dogs to Young Americans.

Why wouldn’t he go deeper into soul, jazz, and funk – and, then, having gone that far, why wouldn’t he go further afield, into hip hop, samba, and “punk country and western”, as he described ‘Here’s One That Got Away’? From the string of non-album Style Council singles released across 1983 (‘Speak Like A Child’, ‘Long Hot Summer’, ‘Money-Go-Round’ and ‘Party Chambers’) it should have been clear that Weller would make the most of his debtlessness after The Jam. “I haven’t any plans for an album”, he told the teen magazine Jackie that year. “I’ll just collect up tracks as I go along. I’m more interested in releasing 45’s really. So people will have to bear with me, expect nothing and I’ll give as much in return.”

Together with this unhurried self-assurance, Weller’s democratic initiative is what makes Café Bleu so distinctive as a debut album and so winning as an experiment in collaboration. Remember that this ensemble did not meet as equals. You have the anointed (if reluctant) voice of a generation, with vast resources available to him and a fanbase still young and fervent, who ended his last band with both a single (‘Beat Surrender’) and album (The Gift) sitting at number one. Then you have – and I mean no disrespect to Mick Talbot or The Bureau – the keyboardist of arguably the lesser of two groups to splinter from Dexys Midnight Runners. Dee C. Lee had only just begun a solo career after her time in (the unsung) Central Line and as a backup singer for Wham! Honorary Councillors Tracey Thorn and Ben Watt were each proven and tempered by March 1984 but had only a single to their name as Everything But the Girl. Steve White, who drums on every track, was 18. It’s clear from Café Bleu that Weller regarded these musicians as peers and influences, not just collaborators. Only a pop star of his stature could have guaranteed them the real estate on his album that he did; only someone who believed so much in the idea(l) of his band would have been so willing to subordinate himself to it.

And it’s not as if Weller the songsmith is nowhere to be found. He knew he was holding an ace and a king, respectively, in ‘My Ever Changing Moods’ and ‘You’re The Best Thing’. He even put the slower, piano version of ‘Moods’ on Café Bleu in the (correct) assumption that the song would find its way to the stars no matter what. There’s also the underrated soul rebel anthem ‘Here’s One That Got Away’, whose chorus may not have been impressive enough to qualify for release as a single but ranks among the exuberant peaks of The Style Council catalogue, a rousing up-yours to the provincial and censorious.

The final track, an instrumental Northern Soul homage called ‘Council Meetin’, is curtain call music for this revue; the real culmination of Café Bleu is the penultimate ‘Headstart For Happiness’. I have always been partial to the light touch of the lovely, earlier version of this song, with its woodblock percussion and Talbot’s soaring Hammond organ. On this reacquaintance with the whole of Café Bleu, though, the sense of spirited determination and teamwork conveyed by Talbot, Weller, and Lee as they trade verses was overwhelming.

Forty years later, it’s easy to be sentimental about the idea of The Style Council, which was an ideal of pop as the soundtrack to a more cosmopolitan, egalitarian, and tasteful mode of “clean living under difficult circumstances”. Insofar as the experiment yielded mixed results, only so much blame can be assigned to market forces and Margaret Thatcher. The Style Council deserves better, though, than what E.P. Thompson, writing of the Luddites, utopians, peasant revolutionaries, and religious fanatics of the early industrial period, called the “enormous condescension of posterity”.

The cooperative instincts guiding Weller’s “mixed-up fury” on Café Bleu produced one of his very best records, because – not in spite – of the fact that his presence on it sounds nothing like dominance. He had nothing to prove about his own capability after The Jam. What found new expression, besides his skill as an arranger and instrumentalist, was his knack for surrounding himself with brilliant fellow workers, with top talent.

And to think, Tears For Fears would sing: “Kick out the style, bring back the jam.” The fucking temerity.