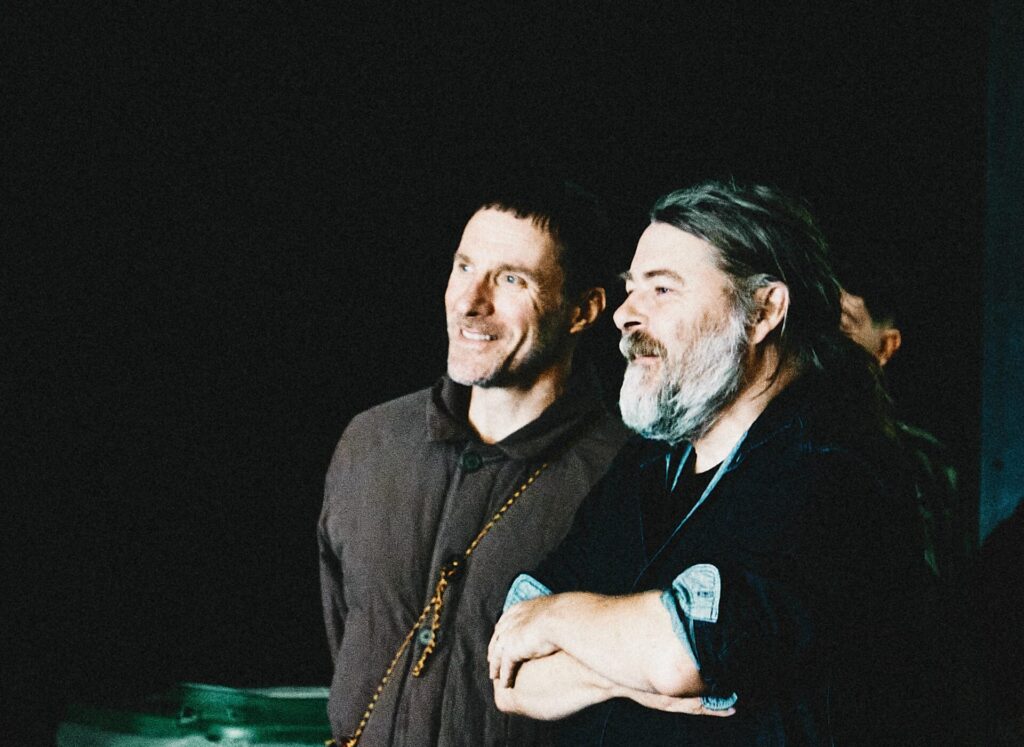

Music writers. Who needs ’em? We recently had the opportunity to get film director Ben Wheatley together with Jason Williamson, of Sleaford Mods, so we left them to interview one another with no interference from us.

After starting out in advertising, Ben Wheatley’s first feature film was the low-budget crime drama Down Terrace (2009). Subsequently, he has released another nine features, including cult black comedy Sightseers (2012), the extraordinary English Civil War-set horror A Field In England (2013) and the big-budget, bigger-shark blockbuster Meg 2: The Trench (2023). His indie science fiction thriller BULK, starring Sam Riley, and the crime thriller Normal, starring Bob Odenkirk, will be released this year.

Jason Williamson fronts Sleaford Mods, the minimalist post punk duo with multi-instrumentalist and producer Andrew Fearn. Their new album, The Demise Of Planet X, will be released by Rough Trade this month. As a young man, Williamson wanted to be an actor. He recently played The Poacher in Game, the first feature produced by Geoff Barrow’s Invada Films.

Jason Williamson interviews Ben Wheatley

Jason Williamson: You co-write a lot with your wife, Amy Jump. When she presents you with writing that hasn’t been co-authored by you, does it bother you?

Ben Wheatley: It’s more of a relief not to have to write something. When I get hold of [a script that Amy has written] that’s really good, I just go, “Fuck. Yeah. Right. Cool.” It’s not like the process is linear. We’re working on dozens of scripts at the same time, so we’re always making films and writing. There is no hierarchy in that. I’ve written a lot of stuff on my own, but it gets more and more terrifying, doing it yourself, because you’re literally the only person to blame.

JW: Why is it terrifying? Because obviously, you’ve written something that you think is good.

BW: I have usually got a safety net in terms of being able to say, “Well, you know, I’m part of a team.” But when I was doing Happy New Year, Colin Burstead (2018), which was the first film I wrote on my own, I was up all night; I had a massive anxiety attack about it. There’s a weird creative FOMO issue as well. You could have done anything at that point. You can’t win, because it’s a fight with yourself. You’re going, “Oh, fuck, why am I making this miserable film about people shouting at each other? I could have done something about a man who finds a puppy and looks after it, and they’re friends.”

JW: You don’t tend to write anything like that though; does being bleak interest you more?

BW: No, it’s just easier. Writing about the bleak is a mode and I lean towards it. Over the last ten years, I’ve been trying not to make stuff that’s fucking miserable. Everybody’s like, ‘Oh, why did he make a film about submarines and a big shark?’ It’s because it’s fun, as opposed to a man bashing his head against the wall and crying. Entertainment’s a spectrum. I like stuff that’s a bit sappy and silly, as well as stuff that’s really miserable. Once you’ve made stuff that’s fundamentally as miserable as you can get, like Kill List, you don’t need to go there again. Or you shouldn’t make a whole load of those movies, one after the other.

JW: Do get a bit pissed off with people talking about your earlier stuff?

BW: In the Woody Allen movie, Stardust Memories, he goes to a film festival. It’s brilliant. These aliens land and talk to him: “We enjoy your films, particularly the early funny ones.” To answer your question: thank God they like some of it. I also find people who enjoy specific films don’t necessarily enjoy the other films. There are still people saying Down Terrace was the best thing I ever did. ‘Where did it all go wrong?’ You can’t combat that.

JW: Do you think it’s getting harder to get your message out there, because there’s so much on offer?

BW: I was on the internet early doors, doing websites. My bread and butter in the late 90s was doing viral adverts, which were designed for people to email to each other. You’d get these massive audiences coming to websites, millions of people. You can’t do that now, and it’s not because there’s more choice, it’s because the aggregate sites, YouTube and Instagram, are controlling how you see stuff. That sounds a bit tinfoil-hatty, but all these places have an algorithm. It’s not as clean as it used to be, when it was just force of numbers.

It’s interesting looking at the promo we did [for the Sleaford Mods’ ‘The Good Life’ single] and looking at how great the traffic has been for that on Instagram. But then I’m looking at my own stuff, and it’s like one hundredth of the traffic. Why is that? It’s the fan base of the Sleafords flushing it through the system, which is terrific. Also, the reach of Gwendoline Christie [the Game Of Thrones star, who features on single and video] is terrifying. I posted something the other day that was getting 20 views or something. Then she gave it a like and it went straight up. I’m like, “Why has that happened? Oh, she’s looked at it, like the eye of Sauron.”

JW: When you went to work on Meg 2: In The Trench, that’s a bigger project. Did you just take your method of working and super-size it?

BW: The thing is, I’ve always done ads, and adverts are pro rata the same budget as big movies. They’re the same effectively, except with adverts you only work for one day and it’s about butter. You get a taste of what a larger crew is like, so it’s not a massive deal. It’s more that you get control over the physical aspects of the movie. When I did High-Rise, it was the first time I got to paint the walls in rooms, physically change the colour. And got to have a graphic design team that would say, “There’s a book in this scene, do you want to have the cover designed?” “Oh, you can do that?” That’s great. You’re controlling the image more and more. The image contains all the atoms of the meaning of the thing.

JW: Over lockdown, we were having an email exchange and you were saying, ‘Oh yeah, I’m drawing pictures of sharks.’ Was it down to you to realise what the shark looked like in Meg 2?

BW: I did draw about 3,000 storyboards. And then they got redrawn by a fancy artist, Jake Lunt Davies. But then I redrew them again on set. As I found out quite quickly, if you get some water, put a shark in it and say, “That shark’s fucking massive!” the problem is, how can you tell? You have to put things in the frame, in-between the viewer and the shark, for context.

JW: Do you use improv with your stuff?

BW: I’ve always used it, but Amy’s scripts don’t have improv in them. With A Field In England, you couldn’t improvise it, because we found that words themselves have birthdates. There is a line in it about envelopes, and afterwards we were like, ‘Fuck, when was the envelope invented?’ And it was actually about a year after the English Civil War. But that was the warning, that if you start waxing lyrical and making up dialogue, you can come unstuck quite quickly.

JW: What was the idea with the black magic in Field? It was completely weird. I watched it – and then I had to read about the film and watch it again. The idea is that you’re not supposed to get it, are you? Yet you are too. After reading about it, it was clear I understood what was going on the first time I watched it.

BW: I figured that, if you were parachuted into the past, no-one would explain anything to you. I was thinking about Minority Report, where there are a lot of characters talking about how the technology works to help the audience out. Although I like that film, I thought, “Well, if I went back to the English Civil War, people would assume that I knew all this stuff. They wouldn’t give me any quarter, they’d just be talking nonsense about their lives.” It’s also part of trying to make you feel alienated and struggle rather than being spoon-fed the experience. One of the characters [O’Neil, the alchemist] has a badge on. That’s about scrofulous. You go to the king and he gives you a coin you’d wear and it would cure the disease. That’s in the film, but it’s never explained. It’s just showing you, and you don’t know why until you look it up – if you want to. It’s more like dialogue as texture.

Ben Wheatley interviews Jason Williamson

BW: Do you recognise yourself in your earlier work?

JW: I do, unfortunately. I recognise myself a lot in my accent, which I don’t really like. My accent reminds me of my family’s accent. It’s almost sobering, representative of remembering what I actually am, which is a peasant.

BW: Well, we’ll see: how fast do you eat your dinner?

JW: Really fast actually. I don’t know if I’m as bad as the dogs, because they worry about their food being stolen. It’s grim, to the point where we’ve had to buy them special bowls. The base of the bowl is a maze, and they’ve got to pick out the bits from among all the little raised bits on the bottom. But I was just hungry as a kid, I just liked food.

Class is all around. You’re stood next to a lot of people that are bigger and brighter, tall, cleaner and nicer. I find myself censoring myself a little bit. I think they’re not going to be interested in me when I talk – [exaggerating his accent] “Ru-ru-ru-ru.”

BW: Is it all despair, or are we just old? Suck on that!

JW: I look at A Field In England, which came out in 2013, the same time as Austerity Dogs, and both things visually were black and white. So is that just because we are similar in our chosen mood boards when it comes to creativity? I don’t know. But if you want to look at things politically, yeah, probably [we are in a bad place]. But then in the 50s, it was the Cold War. Then in the 80s, what about fucking Threads?

BW: It looks really bad now, but the example I always think about is the housing collapse in the 1990s. I didn’t give a shit about that because I was young and I didn’t have a mortgage. It was one of the most upbeat times of my life, yet people who had houses were fucked.

JW: I thought that in 2013. Austerely kicked in, and me and Andrew Fearn were having the time of our lives because we were becoming well known. It was like that completely and utterly dispelled everything else. Perhaps the two things work in conjunction with each other sometimes. It depends on how you view age. I’m getting to the point where I’m not that bothered about getting older, I quite prefer it.

BW: I don’t mind about ageing either. But then my newest worries are more to do with kids. If you’ve got kids, you feel you’ve got a responsibility. Do you find that amplifies what’s on the news?

JW: It does. But then somebody said to me the other day, ‘Look, kids are really strong, you need to remember that.’ My daughter especially was conscious of lockdown, but they just deal with it. I constantly project myself onto my son, but then I have to remember, ‘What about the times where I used to hang around in a park smoking cigarettes at the age of 13? Or building a swing on a tree? Or breaking into cars?’ Bleak shit. Horrible estates at night.

BW: When we did Free Fire, it was the first time we went around the country to support the film. At that point, I thought it was promotion, but what it was really about was meeting the audiences and seeing what the cinemas were like. Different towns have different film cultures in them and different types of attitudes; they are warmer or cooler in different ways. Learning that was important. Is touring similar?

JW: To a certain degree. In 2024, it was more noticeable because we did the smaller venues that we did when we first started and we were doing the Divide And Exit (2014) tour. People came in who were there right at the start, and walked out halfway because these lads are now in shorts and dancing around like fucking Liberace. ‘I’m not having it!’ You noticed there was a bit of a kickback.

BW: Was it their hips? I don’t like standing for two hours, it sucks.

JW: No, I don’t either. Ninety-minute setlists are too long, but you find yourself having to do them. I was reading an interview with Steve Jones from the Pistols and he was saying that after an hour you get bored, it doesn’t matter who you go to see. And we don’t do encores. Is it even alright if you’re doing a Vegas slot? I don’t know. I think at our level it’s just ego. I’m thinking this time around [Sleaford Mods tour the UK in February 2026], because we’ve got so many collaborations on the new album, if none of them are there on stage, I can go off. It will be like one of these old rock bands, Guns N’ Roses in 1992, where Axl Rose would go off for two songs. I said to my wife, Claire [Ormiston, Sleaford Mods’ manager], “Imagine that. It would just look so crap, it would be brilliant!” She said, “No, at this level, Jason, if you look crap, it will be crap…”

BW: Do you see creativity as a whole or specific to different disciplines?

JW: It’s different. For instance, I don’t normally rehearse routines on stage. I just wait for the tour to start and then, when the gig begins, you start trying out new stuff. Coming back to this idea of, if it looks crap, it’s good, I thought, “Well, that kind of adds to what we do because if it was completely choreographed, it would look absolutely stupid.” Because it’s quite uncouth. And that’s obviously different to writing the songs in the studio. Overall, for what we do, what I’m interested in is for it to look totally realistic, how it is.

BW: What about acting?

JW: People are like, “Oh, are you just looking for interesting parts?” And I’m like, “Well, that’s just stupid. No, I’m not. I’ll do it.” You do anything. I enjoy the process of what can you make this do? And will it suit me anyway? Will I pull it off? You could be a bartender in EastEnders. Or down in the kitchen in Rebecca [Wheatley’s 2020 film version of the Daphne du Maurier novel, in which Williamson appeared]. Or playing a poacher.

BW: Do you have a Sleaford grand plan? And what does that look like?

JW: No. The only plan is to write good music and keep it interesting. I mean, if people don’t like what we do, we’re fucked anyway. So it doesn’t matter to those people what we do; they’re still not going to be impressed.

The Demise Of Planet X is released via Rough Trade on 16 January. Ben Wheatley will embark on a Q&A tour to accompany screenings of BULK on 15 January